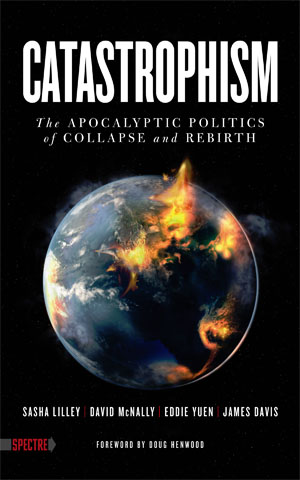

In the January-February International Socialist Review (ISR), Dan Sharber described the book Catastrophism as “a superb intervention into a necessary debate on how we move forward, not simply in the environmental movement but also in the larger project of social change.”

I disagree. The book applies the label “catastrophism” to such a wide variety of political views and strategies that it loses all coherence. What possible analytical or strategic value can we find in a category that includes everyone, right wing or left wing, socialist, conservative, liberal or reactionary, who forecasts, expects, fears, desires, promotes or opposes economic, social, cultural, moral, or environmental disruption?

What concerns me right now, however, is the one essay in Catastrophism that focuses on current movements. Eddy Yuen’s critique of environmentalism, “The Politics of Failure has Failed,” is a prescription for abstention and defeat.

In his review, Dan writes: “Now more than ever we need a set of politics and beliefs that can explain the causes of the catastrophes facing the planet today while offering real and realistic solutions.” That’s exactly right. Socialists must, as they did with February’s mass march against the Keystone XL pipeline, join in building struggles against global warming and other environmental crimes, put forward a clear analysis of the crisis, and help develop and call for concrete solutions.

But that’s not what Yuen says. He argues that building movements to stop catastrophic climate change is counter-productive, because talking about environmental disasters (a) turns people off and makes them apathetic; and, (b) promotes reactionary policies and strengthens the ruling class.

Perhaps Dan was misled by the fact that Yuen is no climate change denier. It is hard to believe that someone who accurately says we face “a genuinely catastrophic moment in human and planetary history” would tell radicals to stop telling people about it. But that’s what Yuen does.

He doesn’t just say talking about climate crises may cause mass apathy, he says it already has. He says that environmentalists, by warning of environmental crises — that’s what he means by “catastrophism” — have actually undermined popular concern about the problem.

His only evidence for this is a 2008 telephone survey that purportedly found that people who are “more informed” show less concern about the threat of climate change than people who are “less informed.” If he had read the original study (his footnotes only reference journalists’ reports) he would have found that the survey didn’t ask people who claimed to be “more informed” what they actually knew or believed about climate change, so the survey result was meaningless.

Other data convincingly refutes Yuen’s argument. For example, a recent study published by Yale and George Mason Universities shows that even before Hurricane Sandy, more than twice as many Americans were alarmed or concerned about global warming than are doubtful or dismissive — and the gap has grown since 2010.

Yuen is repeating the myth that liberal politicians and journalists use to justify their failure to challenge the crimes of the fossil fuel industry. People are tired of all that doom and gloom, they say. It’s time for positive messages! (Or, as Yuen puts it, environmentalists need to end “apocalyptic rhetoric” and find better “narrative strategies.”)

In fact, as climate change expert Joseph Romm wrote recently in his Climate Progress blog, “it is total BS that somehow the American public has been scared and overwhelmed by repeated doomsday messaging into some sort of climate fatigue.” Romm shows that few Americans have been exposed to any “doomsday messages,” let alone enough to be frightened or bored into apathy. For years, accurate information about the climate crisis has been almost impossible to find in major U.S. media.

Despite the lack of evidence, Yuen not only argues that getting out the truth about environmental crises causes apathy, but insists that it “disables the left but benefits the right and capital.”

Increased awareness of environmental crisis will not likely translate into a more ecological lifestyle, let alone an activist orientation against the root causes of environmental degradation. In fact, right-wing and nationalist environmental politics have much more to gain from an embrace of catastrophism.

He devotes much of his essay to the efforts of right-wing forces to use concern about environmental crises to promote their own interests, ranging from emissions trading schemes to expansion of the military to Malthusian attacks on the world’s poorest people. “The solution offered by global elites to the catastrophe is a further program of austerity, belt-tightening, and sacrifice, the brunt of which be borne by the world’s poor.” In Yuen’s view, environmental warnings only strengthen support for such oppressive measures.

The idea that ruling class interests are usually opposed to the interests of the rest of us may be a revelation for pale-green liberals who believe that “we’re all in this together,” but it has been central to left-wing thought since before Marx was born. Capitalists always try to turn crises to their advantage, and they always try to win popular support for their “solutions.” The question is, what do we do about it?

Contrary to Yuen’s title, the effort to build a movement to save the planet has not failed. Indeed, Catastrophism was published just four months before the largest U.S. climate change demonstration ever!

Yes, the movement has a long way to go, and no, it isn’t perfect. Yes, there are reactionaries and Malthusians involved. Yes, liberals are trying to steer the movement to meet the needs of Democrats and corporations. That’s exactly why we must be there, too. If every movement sprang from the ground with a perfect program and no confusion or backward ideas, then radicals could sit back and watch. But reality isn’t like that.

If radicals are serious about fighting capitalist ecocide — and simple survival says we’d better be — then we need to help build a real mass movement. That means working with any allies we can find who agree on immediate objectives, arguing for independence from capitalist parties, and as Dan Sharber says, explaining the causes of the catastrophes facing the planet today while offering real and realistic solutions.

But for Yuen, trying to mobilize protests against capitalism’s crimes is passé, a naïve effort to replicate the radicalization of the 1960s using an outmoded “narrative strategy.” Instead we should be “voluntarily engaging in intentional communities, sustainability projects, permaculture and urban farming, communing and militant resistance to consumerism.” He particularly likes the example set by Italy’s “Slow Food” movement.

Those are undoubtedly worthwhile activities, but as a veteran of the sixties, I remember how many activists stopped protesting to form “intentional communities” — called communes in those days — and were thus lost to the movement. So I’m dubious about that approach. And if Yuen believes capitalism can’t turn such projects to its own ends, he’s very naïve.

More importantly, such activity is no substitute for actually working to stop the environmental crises that are bearing down on us. No magical narrative strategy will guarantee victory, but if radicals stand aside from building mass movements to stop capitalist ecocide, then liberals and Malthusians will have a free hand — and that will guarantee failure.

Ian Angus is an author and the editor of Climate & Capitalism.

A note from Ian Angus: The January-February 2013 issue of International Socialist Review (ISR) carried a favorable review of the book Catastrophism: The Apocalyptic Politics of Collapse and Rebirth (PM Press, 2012). While the book contains valuable material — I particularly liked David McNally’s essay on the imaginary and real horrors of capitalism — I found what it said about the environmental movement to be fundamentally wrong-headed. So I submitted the above response to ISR, and the editors have kindly published it in their March-April issue.

This review is reprinted here with permission.