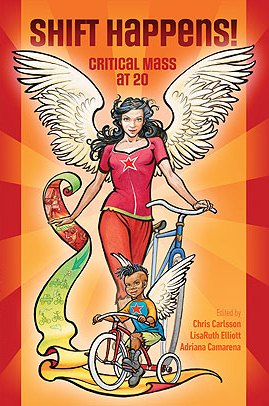

Realizing that 20th anniversary of Critical Mass was less than a year away, late last year we put out an international call for thoughtful analyses. We wanted to go deeper and further than the 10th anniversary book had done. Shift Happens! is the result, and we are extremely happy with the quality and breadth of the writing we received. Several dozen contributors and a wide range of experiences across the Critical Mass world fill these pages, where the original concept is still recognizable but has also mutated and shifted over time and space in fascinating ways…

Critical Mass was born 20 years ago among dozens of people in San Francisco and has reproduced itself in over 350 cities around the world thanks to the diligent efforts of countless thousands across the planet. Often just a few people start riding together and it attracts others to join, gaining momentum steadily until it bursts onto a city’s political and social landscape. Moreover, the concept of riding together en masse is open-ended enough that people have adapted it in many ways during the past decades, from altering the structure of formal recreational riding to using “Critical Mass-style” rides to bring attention to a wide range of political campaigns and issues.

And as we learn from some of the essays in this new collection, mass bike rides weren’t invented in 1992. They took place in different parts of the world years before we started in San Francisco, notably in Bilbao, Spain and Helsinki, Finland where our writers describe earlier rides. Chinese cities were full of bicycles as primary transportation for decades; observing traffic patterns in 1991 Shanghai from a hotel window, New Yorker George Bliss described how bicycles would pile up at the side of a flow of traffic until they reached “critical mass” and broke through to create their own traffic stream — this is where our name came from. Not far from where I lived as a boy in North Oakland, early ecological activists staged an annual mass bike ride called “Smog-Free Locomotion Day” on Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue from 1969-71. In the deep social genes of San Francisco itself, mass bike rides of 5,000-8,000 cyclists jammed muddy, rutted streets a century earlier, in 1896, to demand “Good Roads” and asphalt (unknowingly setting the stage for the next vehicle of speed, convenience, and personal freedom that soon followed: the automobile). My mother was born and raised in Copenhagen where I visited as a small boy and then again in 1977 as a young adult — the sensible organization of public streets with space dedicated to bicycle transit was self-evidently preferable to the freeways and rigid, car-dominated street grids of my California childhood.

Critical Mass was a new beginning, but it grew quite naturally from fertile ground where many different seeds were germinating. When it finally emerged 20 years ago it was a hybrid product of late capitalist urban design, long submerged anarchistic political ideas, a growing refusal to submit to the imposed necessity of embedded technologies, and an urgent reclaiming of cities as a lost public commons. The ease with which it replicated itself across the planet was eloquent testimony (and a creative rebuttal) to the creeping monoculture shaping city life everywhere…

—

During the 20 years of Critical Mass, daily cycling has increased enormously in San Francisco, by a factor of 10 for sure, and maybe a 20-fold increase. The San Francisco Bicycle Coalition’s many years of diligent lobbying for painted bike lanes and sharrows and signed bike routes has finally shown some results in the last few years. They take the lion’s share of credit for the stunning increase in daily cycle trips in San Francisco, but let’s face it — without the mass seizure of the streets by self-organized bicyclists for a few hours at the end every month for the last 20 years, the bicycle culture here would not have become what it is today. (The Bike Coalition itself wouldn’t be what it is today either — it was nearly dormant when Critical Mass started and now it has over 12,000 dues-paying members.) And that broad bike culture — encompassing do-it-yourself bike shops, recreational rides, historic and cultural bike tours, cycle rodeo, choppers, tall bikes, velodromes, spontaneous moonlight rides, the recent Bike Party, et al — is the real foundation of the urban transformation that has still only just begun.

Most fundamentally, Critical Mass is a reclaiming of public space from a culture bent on privatizing everything and reducing human life to a series of commercial transactions. Critical Mass always existed outside of that logic, a zone of free association without buying and selling as its defining activities. We’re reinhabiting city streets on a new basis, reinventing them at least temporarily. We roll along, never stopping, so it’s a fundamentally mobile public space, changing with the geography and the ebb and flow of participants. We don’t petition the government, we don’t ask for reforms, we don’t make demands, we just get on with making and inhabiting a world we can only dream of the rest of the month.

In other parts of the world, especially Italy, Hungary, Brazil, Mexico, and Spain — all well represented in this book — Critical Mass has been an important incubator for new political energies to coalesce, and new initiatives addressing broader questions of city life have emerged, especially regarding the natural ecological systems of cities, water use, climate change, urban agriculture, and much more. Critical Mass is a phenomenon that goes well beyond mere bicycling. Contributors Reboredo and Vázquez from A Coruña, Spain call it a “global prototype” and link the ride’s form to the upsurge of horizontalist political initiatives sweeping the planet. Collective writers from Budapest, Hungary, and Rome show how urban transportation, planning, and politics have been transformed by sharply pointed, creative tactics of cyclists, using mass rides to make much deeper changes.

Measuring the full impact of an amorphous social phenomenon like Critical Mass is probably impossible, in no small part because with non-organization, there have never been any declared goals. But the experience of self-organized mass bicycling for tens of thousands of people hasn’t just disappeared into nothing. Brazilian Tatiana Achcar describes how connecting to the global Critical Mass experience transformed her life and led her to being an autonomina (an “autonomous girl,” in a Portuguese neologism). In Porto Alegre I asked a woman I found myself riding alongside how long she’d been participating in Critical Mass. She told me she’d started the month after the banker drove through the ride in February 2011 (see Marcelo Kalil’s poignant article for a full account). She continued riding, because as she told me, “Since I started bicycling, I’m just happy all the time!”

The logic of Critical Mass is now in the deep wiring of local politics and activism in the San Francisco Bay Area and in many other places across the world. As Ellie Blue’s essay in this volume shows, the recent Occupy movement across the U.S. has found many Critical Mass veterans at the heart of it. Her article also shows how “bike swarming” emerged as a tactic in West Coast actions in Fall 2011 to support and supplement the Occupy movement. Looking further abroad, the indignados and occupied social centers in Spain and Italy closely overlap with Critical Mass cyclists, and frequently cross-pollinate in new and exciting ways. Articles from the PEDAL ride to Palestine, and the ongoing Ecotopia rides across Europe, show how long-distance cyclists connect to Critical Mass communities along the way, and use Critical Mass-style rides to attract new participants as well as garner more attention for their respective causes…

The last vestige of a public commons is our streets, even if modern city dwellers generally fail to make full use of them as such. The streets and highways also serve as the vital arteries of a globalized capitalist economy, creating pressure to keep them as open and rapidly moving as possible. Often overlooked, the mass seizure of public thoroughfares by cyclists on a monthly basis connects with tactics chosen by populations as diverse as the indigenous of Bolivia’s El Alto to the urban poor of Argentina, where blockading roads has been a powerful way to take political action in the past decade. When precarious workers, tech professionals, waitresses, bike messengers, nonprofit office workers, etc. ride together they are connecting to a much deeper and broader political rising in the early 21st century, where the logistical “bloodstreams” of capitalist commerce are the most vulnerable points of leverage for oppositional movements. Further, as relatively wealthy workers choosing to use bicycles, transportation traditionally associated with poverty, perhaps it opens opportunities for new forms of cross-class solidarity.

Where the Left conceived of factories as the primary site of social contestation (and they are still vitally important to the reproduction of daily life, whether the capitalist status quo or the possibilities of a self-managed utopian future), with the fragmentation of work and careers, the unifying terrain of daily life emerges as the public streets. It is where we all meet, where we all have to be on a daily basis, and where we can actually bring the system to a halt with mass action. Critical Mass cyclists, even those who have only come once or twice, have had this knowledge insinuated into their toolkit. Their social and political imaginations have been altered forever by participating in a Critical Mass experience, along with their sense of political and historical agency.

The dynamism and innovative political initiatives documented in profuse detail in this remarkable collection show that the spirit of Critical Mass is very much alive. It still inspires people in many cities and many different countries to come together on bikes to confront the March of (Stupid) Progress. Dreams of human-focused city life where cars are relegated to a subordinate role as a bad transit option are reinforced and renewed by Critical Mass, Masa Critica, Critichella, KritikONA, El Paseo Nocturno, Cyklojizda, Bicicletada, Ciemmona, Velorutión, Criticona, Bicicrítica, and all the global expressions of cycling citizens taking things into their own hands. On a planet confronted by unprecedented crises — economic, ecological, social, and technological — the ongoing public experimental zone opened by Critical Mass is a crucial laboratory for reinventing how we live together on Earth.