Dionne Brand’s novel Theory opens with a short, footnoted, epigraphic introduction: “Occam’s razor.” Occam’s razor is a principle for solving problems in which the simplest solutions are considered the most truthful. This anything-but-simple footnote fills the remainder of the page, spilling over to the next, in which the narrator speaks about turning 40 soon, their incomplete and ambitious PhD dissertation, and a recent uneasy visit from their brother.

The visit reminds the narrator how kinships and lovers have interrupted their intellectual pursuits. They decide to take stock of the reasons for why the dissertation is incomplete. Abiding by the principle of Occam’s razor, the narrator simplifies the reasons to three women: Selah, Yara, and Odalys, each of whom are accorded a chapter.

Brand, a doyenne of Canadian literature, wastes no time establishing the curious, vain, and misinterpreting narrator. We are given a narrator who misunderstands Occam’s razor as they name their three lovers as the reasons, rather than the solutions, for their incomplete dissertation. Brand immediately alerts the reader to this narrator’s unreliability. They will misread people, events, and experiences in their life, Brand seems to say. Now you should read their story.

Atypical in Brand’s corpus and released alongside her poetry collection The Blue Clerk, Theory is a collection of intimate moments depicted through a prism of philosophical deliberations. In an interview, published in Quill & Quire, Brand says that “the thesis that the narrator tries to attend to walks into the novel; the thesis is performed in the novel.” While the academic sermons, like one about art and artists as the narrator musters up courage to call the artist-activist Yara, can be exhausting at times, one realizes that graduate students, like myself, actually do sound like that. Further, the philosophies are important interventions that resemble the work of David Chariandy, Christina Sharpe, Rinaldo Walcott and others, as Brand seamlessly writes their voices into the narrator’s monologues.

Puncturing the intellectualizing addresses, however, are insightful descriptions of the everyday tragedies of love and the sublime of what the narrator calls the “quotidian.” For example, when with Yara, the narrator forgets their work and “experience[s] the world at the level of the skin.” This whirlwind affair represents how love has the power to rearticulate our way of being in the world. Though a revision rather than subversion of the clichés of romance narratives, the expression of this love, both thoughtful and thoughtless, is reminiscent of the style Brand has become known for in such novels as 2005’s What We All Long For.

One does not need to be a Black feminist, queer lover, or graduate student to be unexpectedly arrested by the narrator’s devotional obsession with their partners and dissertation, all articulated in cogent and evocative prose. Nonetheless, the novel does resonate uncomfortably and powerfully across queer, feminine, and people-of-colour readers with experiences in Western academia.

In this prose, one can fully register the many meanings of Teoria, a name given to the narrator by their ex-wife Odalys, which means theory and, from its Ancient Greek roots, “spectator.” The reader is bound to Teoria, the spectator, and therefore to their academic perspectives, which, as the narrator admits, are guilty of misperception and misreading. The narrator references theories from Western Enlightenment and Postcolonial discourses first, but is also influenced by the theories lived and believed by Teoria’s lovers. In the final chapter, the narrator recognizes the false dichotomy they set up between theories of the mind, represented by white philosophers like Roland Barthes, and those of the body and soul, represented by Odalys. The final chapter attempts to interrogate this binary.

What does not get interrogated are the issues with spectatorship itself. The narrator is a self-professed observer who becomes inspired at different times with different lovers, much like the intellectual figure who observes the social sphere for artistic means.

While the novel problematizes the academic act of referencing other texts — how can one truly obtain the consent for referencing other works, or, how does one ask for consent for writing that by nature is unpossessable, unowned, and shared? — it does not address the problem of referencing other lives without consent.

In A Map to the Door of No Return (2001), Brand narrates a time when she saw a distraught man walk into a square in Amsterdam and how she later used her memory of this stranger to create a moment for a character in At the Full and Change of the Moon (1999). This passage suggests that the act of writing is an articulation of various lived experiences, a fact of the literary process; but while Theory criticizes discourse, citational practice, and many other aspects of writing, I wonder why it neglects to question the ethics of reading other individuals as artistic material, or in the narrator’s case, as theoretical material.

While I hope Brand’s future work explicitly addresses this reality of the writing process, this critique of Theory is perhaps better aimed at the narrator than at Brand. That is the brilliance of this novel. The reader is made to do a lot of work with an unreliable and flawed narrator.

In struggling with, laughing at, or sympathizing with the narrator, I am made to feel the heart of intellectual and ethical issues today: racialized women in academia, the sexualization of women, the politics of heteronormativity, queer countercultures, free speech, resistance in language, and stalled graduate work whose incompleteness has the potential to disrupt the capitalist machine of intellectual labour and its production of use value.

To be able to understand the complexity of these issues is Dionne Brand’s reward to us for our labour as readers.

Tavleen Purewal is in the Doctoral Program in English at the University of Toronto, where she works on Black Canadian and Indigenous literatures.

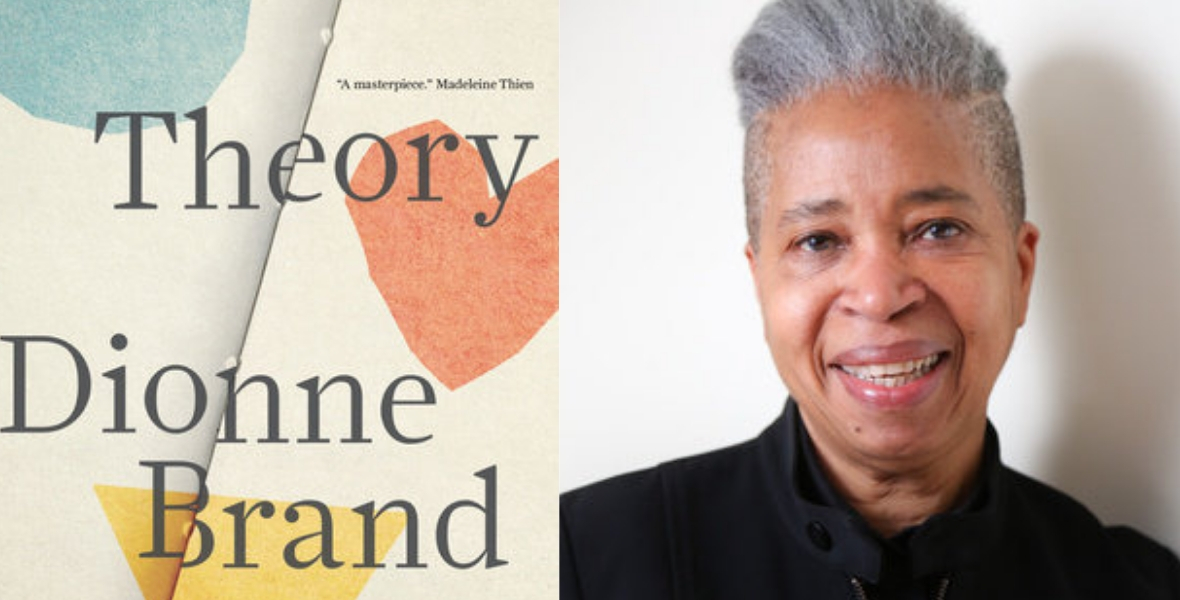

Author image: Jason Chow

Help make rabble sustainable. Please consider supporting our work with a monthly donation. Support rabble.ca today for as little as $1 per month!