Many of us of a certain generation have memories of meeting Vietnam War draft resisters in the 1960s and early 1970s as young American men who sought refuge in Canada and made new lives here. What we haven’t been exposed to as much is the story of their struggle at home to avoid fighting in an unpopular foreign conflict. Now author and former draft resister Eli Greenbaum has opened the door to a renewed understanding of the pain, sorrow and sheer chutzpah of some of the men who defiantly chose not to go.

To some readers, this collection of intimate oral histories could serve as a Saul Alinsky-type guide to future resistance movements. It could even be a textbook for a new generation of draft resisters who view all war as wrong. For the next four years of what promises to be a vindictive, violent and vengeful administration in the U.S., American youth may need it as much as ever to save America from itself.

Some readers might also see this frank recollection of Vietnam War draft resisters as coming too late, but Greenbaum makes up for the tardiness of its arrival by sharing resisters’ trauma and courage in the wake of a United States government bent on destroying the southeast Asian country at all cost.

In the end the cost was the lives of 58,000 American soldiers and the lives of more than two million Vietnamese. The livelihoods of farmers were demolished through B52 bombardment and the spread of the exfoliant Agent Orange. Families were ripped apart and friendships severed. The legacy of those years still haunts the men interviewed for the book.

The first few chapters cover the war’s history, the U.S. protest movement and the dynamics of selective service draft boards. In the author’s case, this included the terror of meeting the board secretary. It was invariably a woman entrusted with the power to defer you or send you to your death in the rice paddies and jungles of Vietnam. Greenbaum’s board secretary was Mary Modelski, “a personal nightmare” who relished holding his fate in her hands.

Canadians of that era are thankful to have been able to avoid that “less than pleasant” experience. But not all of them agreed. In my 1981 feature article for The Globe and Mail I searched for reasons why Canadians would enlist in that war. I interviewed General Jacques Alfred Dextraze, chief of defence staff in Canada from 1972-77. I was shocked to learn that his son Richard had died fighting in Vietnam.

“People brand them as stupid and fools,” he said of his son and upwards of 14,000 Canadians he claims may have also signed up. “They forget the reasons they went to fight” he added. Richard went overseas “to fight these Communists.”

For Greenbaum and others, fighting communists was not a good enough reason to participate in what was ultimately seen as a terrible mistake based on political paranoia fueled by the domino theory of a communist world takeover. But Greenbaum is clear that “This is not an anti-war treatise.” He believes there can be just wars as do others in the book.

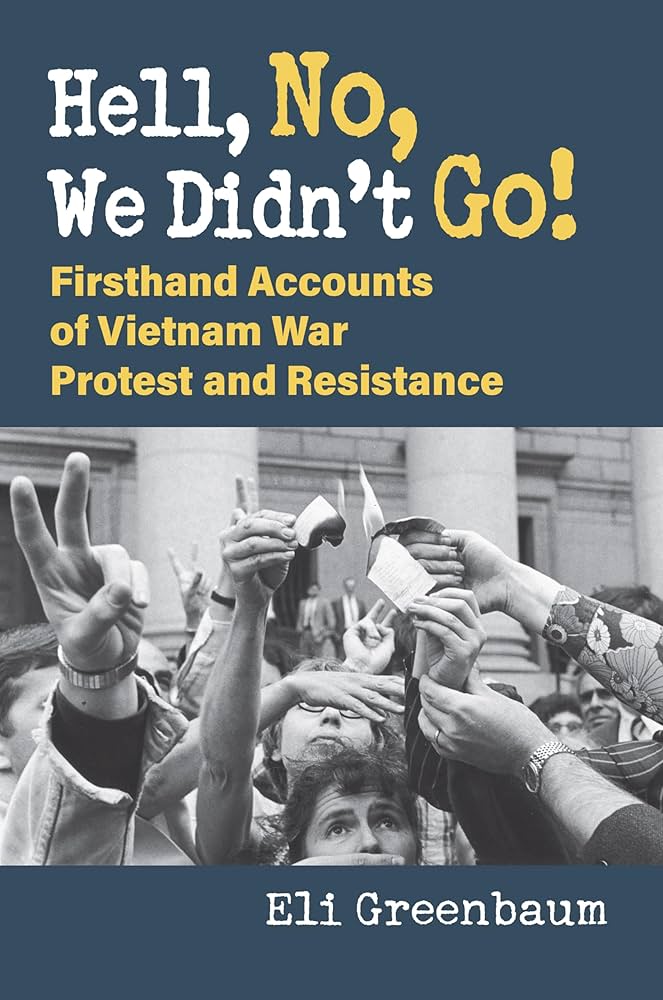

Instead, this is a narrative about “what we were thinking when we sang anti-war songs, marched in protest, held sit-ins and teach-ins, turned in or burned draft cards, and refused to buckle under the orders of what we believed to be misguided and often disingenuous American leadership.”

Greenbaum had a student deferment to study law at Wayne State University, but draft board secretary Modelski learned that he had written a letter to President Lyndon B. Johnson opposing the war. He also submitted a foreign travel request. In no time, he found himself moved up to category 1-A, meaning fit for service. He “naively thought” [his] student deferment (2-S) would protect him. Instead his name climbed closer to the top of the list. It seemed the Selective Service Act could serve as “a device to punish dissent.”

The rest of the book is divided into chapters that cover various ways people attempted to avoid the draft, including the hope that once Richard Nixon’s draft lottery system was instituted in 1969 they would draw a high-enough number to avoid military service.

It was unnerving to wait for your number to appear (a sample chart is supplied in the book) or to undergo the daily horror of getting a call from the draft board. It’s not possible to compare experiences with those men who were ordered, on pain of imprisonment, to endure a rigorous physical exam to determine their suitability for war. The men interviewed all describe a frightening and nerve-wracking ordeal with potential inductees being poked and prodded to effectively decide whether they were fit to get shot.

“To be blunt,” Greenbaum writes, “the draft equalled potential death, and no way would we become cannon fodder” to fight what was seen as a civil war thousands of miles from home that did not directly threaten the U.S. But to be equally blunt, Greenbaum professes love for his country. “We just weren’t crazy about our government,” he writes.

On arriving for the finishing the physical exam, most men hoped for a 4-F designation. To get it, many did everything from shooting off a toe to outfitting themselves with braces or feigning high blood pressure or ingesting a dangerous substance. Others employed different strategies.

It was rumoured that if you faked being gay you could get you an instant deferment. A scene in filmmaker Paul Schrader’s new film Oh, Canada, starring Richard Gere, depicts such a success. That option “didn’t work – unless, perhaps, you really were gay,” Greenbaum explains. “Some men defecated and urinated in their underpants and didn’t bother changing them for the physical.”

Applying for conscientious objector (CO) status was another potential escape. But this, too, was a difficult play. First, applicants had to prove the sincerity of their bid. Those who did succeed might be classified 1-O or 1-A-O which meant you could serve in the army as a medic, clerk or other role that did not require using a weapon.

A draftee could also avoid service by joining the West Point Band, formally known as the United States Military Academy Band. “Once I was at West Point,” wrote one man, “I found that many of my bandmates, like me, had signed up to avoid the draft.”

Being ordained in the non-denominational Universal Life Church might get you a pass, but it usually didn’t work. Signing up for yeshiva (Jewish school) could also get you out of serving in Vietnam. “Students enrolling in the yeshiva received a highly sought-after perk: a 2-D classification and the accompanying draft deferment,” the book reads. These fortunate men might never become rabbis, but they could enjoy the perk.

Signing up for Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), President Lyndon B. Johnson’s anti-poverty program, was yet another possibility although it could also backfire as an exit strategy. The Peace Corps was a potential avenue out, but again not always successful. And, of course, there was a final option: move to Canada. But this could also be difficult.

In a chapter called “Go North, Young Man,” Greenbaum estimates that 20,000 to 100,000 men moved to Canada. They “decided that resettling across the border, wearing sweaters more often, learning all about hockey and curling, and eating poutine . . . would be just fine, much better than training for combat and being sent off to hot and humid Southeast Asia.” Here they found a not-always warm welcome – “some Canadians resented the flood of Americans” – but resisters often received help from the local anti-war movement.

Greenbaum also interviewed men who served in Vietnam and returned opposed to the war. They joined Vietnam Veterans Against the War and protested alongside the vast army of protesters on campuses and off. He also discusses women’s role.

Although women weren’t engaged in combat, the mothers of draftees were in the fight to save their sons. Younger women, too, got into the anti-war battle.

“Obviously, we women didn’t have draft cards,” Psylvia Gurk, said, “but we stood up and gave our names in solidarity with the men. I felt as if I was a draft dodger too.”

Another woman, Jane, spouse of Senator Philip Hart, sometimes called the “Conscience of the Senate,” flew into action to help a man obtain a deferral.

“She had visited North Vietnam to meet with American prisoners and was arrested with dozens of other protestors at the Pentagon during a peace demonstration,” the book reads.

Greenbaum also mentions several famous anti-war protesters such as Tom Hayden, the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) co-founder, but neglects to discuss his spouse, actor Jane Fonda’s, prominent anti-war role as “Hanoi Jane.”

Mohammed Ali is credited with defying the draft board by declaring conscientious objector status due to being a Black Muslim. “He embellished his position with a now-famous statement, ‘I ain’t got no quarrel with the Vietcong. No Vietcong ever called me nigger,’” Greenbaum writes.

Greenbaum stresses the “white privilege” aspect of draft board deferment choices. Many of those interviewed were from well-off families with influential contacts. Almost all of them went on to higher education, good jobs and life achievements.

Some expressed guilt based on their success in opting out, but none were prepared to fight and possibly die in Vietnam. At the same time, they did not try to shame those young men who did fight. For some, they realized joining the military was the best option they had for creating a future. The G.I. Bill would pay for their education. The military could train them in a trade. Veterans Affairs offered mortgages.

One draft resister rejected the notion that he was being unpatriotic. “The pervasive requirement that people behave patriotically is just a widely accepted form of political correctness that coerces support for militarism, colonialism, capitalism, and racism. Being labelled unpatriotic is fine with me,” the book reads.

Photos accompany some of the interviews, but there are no images of the angry protests that occurred at the 1968 Democratic Party convention in Chicago, or the 1970 Kent State University killings of students by President Richard Nixon’s National Guard. While mentioned, there are no visual reminders of the great anti-war marches and music and cultural events of the time.

One exception is the inclusion of a poster with the headline “Girls Say Yes, to Boys Who Say No.” It features a photo of folksinger Joan Baez and her two sisters. But more often the photos are of resisters then and now, keeping the focus on their stories not the national news stories of the day.

Note: Kathleen Rodgers wrote a similar account of resisters called Welcome to Resisterville: American Dissidents in British Columbia (UBC Press, 2014) that offered memories from the Canadian side of the border.