Fearmonger: Stephen Harper’s Tough On Crime Agenda

by Paula Mallea (Lorimer 2011; $24.95)

It’s a rare event in the Canadian publishing world when non-fiction books line up in sync with current events, but these two titles are perfectly timed as Canadians consider the serious consequences of the Harper government’s dramatic omnibus crime bill, one that will radically alter an already deteriorating judicial system.

The legislation has drawn a broad range of critics from across the political spectrum, and a refusal to provide a public costing of the bill was a contributing factor in the fall of the last minority government. But as with all things emanating from Ottawa, there has been little detail and much obfuscation about the central issues. Those who’d like an inkling of what could come down the pipe can do no better than read Paula Mallea’s appropriately named Fearmonger, an outstanding overview of recently passed and proposed crime legislation.

Written in an accessible manner while reflecting the author’s own extensive background in criminal law, this analysis picks apart each of the Conservative crime agenda’s multi-pronged proposals based on an objective, reality-based approach that can hardly be accused of partisanship. Rather, Mallea cobbles together research, expert voices and common sense refutations that illustrate how an indefinite increase in punishment for punishment’s sake will in fact make society less safe and cost untold billions in the process.

Indeed, Mallea presents statistics indicating the majority of people already in prisons — the mentally ill, substance abusers, the economically disadvantaged and, in disproportionate numbers, First Nations — are there due to systemic bias and a failure to invest properly in the social programs that would keep these folks from falling through the cracks in the first place. Also lost in the tough-on-crime rhetoric, Mallea says, is the fact that Canada’s sentencing laws for serious offences are already among the harshest among western democracies, even eclipsing those of the U.S.

Why is it, Mallea asks, that at a time when various American states are realizing the folly of their massive investments in the prison-industrial complex, Canada appears headed down the same path? The answer appears to be purely ideological, as Harper and his ministers do not wish to have the facts interfere with their version of reality. Fearmonger illustrates how the crime rate continues to decrease while incarceration rates go up, and that cornerstones of the Harper argument, from mandatory minimum sentences and the alleged deterrence effect of long years in the penitentiary, are simply not supported by the conclusions of everyone from chiefs of police to Corrections Canada itself. But the crisis in prison overcrowding, the diminishing number of rehabilitative programs, and the warehousing of nonviolent offenders are all set to skyrocket unless there is a serious pushback.

Anyone from a recreational drug user sharing a joint to a teenager caught joyriding is slated to be caught up in the Harper regime’s broadening law and order net, and the courts can expect to become even more backed up with constitutional challenges and judges wrestling with how to craft appropriate sentences under a scheme that will allow them very little discretion.

Mallea argues there is another way, examining successful alternative models both in Canada and abroad, largely based on restorative models of justice that deal with the rips in community fabric that result from crime while exploring prevention strategies that keep people from courting the kind of trouble that sends them behind bars to begin with.

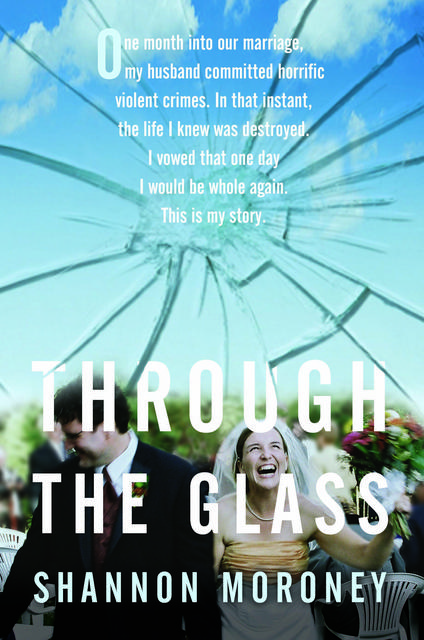

It’s that alternative way of seeing crime that is at the heart of a brutally honest first-hand account of going through the current system written by a woman whose husband was designated a dangerous offender after he kidnapped and sexually assaulted two women. Through the Glass could have been a simple-minded rallying cry to abandon such perpetrators to deal with their sins while forever locked away, but is instead, in the hands of Shannon Moroney, a well crafted journey through the nightmare of Canada’s courts that painfully illustrates how many victims of crimes are never truly accounted for in the trial process.

Rather than jumping on the Harper bandwagon, though, Moroney shows that what she experienced will only be multiplied endlessly under a regime that fails to take account of the multi-faceted sources of violent crime and the utter failure to provide prisoners the tools they need to deal with the issues that led to their arrest and incarceration.

Moroney had married an abuse survivor, Jason, who at a young age was convicted of murder; he served his time, was a model prisoner and, based on her inquiries with corrections officials, appeared to be fully rehabilitated. But while in the system, he never addressed the root causes of his original crime, and a month into their happily married life, she was informed while on a trip to Toronto that her husband had committed an awful crime, and then reported himself to police.

While Jason sits behind bars, Moroney finds she is the one who has to deal daily with the consequences of his actions, from close friends turning on her to her employers casting a suspicious eye on her as well. She is also a victim, yet there are no services for her as she tries to piece her life back together. She also makes the crucial decision to stay in touch with Jason, as she deserves an explanation for what happened just as much as everyone else who has been affected by his crimes.

But every step of the way she hits institutional walls: how can Jason get the treatment he needs, especially after he did his first stretch in prison like a robot, shut down emotionally and completely disconnected from the source of his rage; how can his willingness to plead guilty have no impact on the snail’s pace journey toward a trial date (and the beginning of some sort of resolution); how can she and her family deal with the fallout that must be faced everyday though they themselves have committed no crime?

As part of her own desperate search for answers, Moroney comes to conclusions that lead her to investigate restorative justice, the very thing Harper is discarding in their Canadian infancy. She learns that the court system views crimes as assaults against the state, whereas she comes to see that crime is in fact a breach of relationships of trust. The answer, she learns, is not to literally absolve someone of responsibility by placing them somewhere that they never have to see or hear from the victims again, but rather, a process by which relationships can be restored. This approach widens the circle of those whose lives have been forever changed by a tragic act, and allows for the type of healing that will strengthen community and prevent further harm.

Moroney attempts to incorporate these principles into the trial process itself, as well as in her dealings with former employers who feel she can no longer work for them. Some are open to the approach, others not. But when Moroney receives a bear hug from one of the sexual assault victims, there is a two-fold recognition: that the web of those deeply hurt by one man’s acts is so much wider than most courts will ever recognize, and the potential healing effects of dealing with the aftereffects of crime in community, not isolation, are limitless.

Moroney’s Through the Glass shows all is not well with the system that Harper thinks is too soft on crime, and she continues her work on the art of forgiveness and restorative justice with public talks and workshops (see more at ShannonMoroney.com).

And so, as the Harper government seeks to ram through its legislation before the end of the year, those seeking tools to stop the juggernaut have two very reliable, informative tools to assist in that struggle.—Matthew Behrens

Matthew Behrens is a rabble columnist and social justice advocate who coordinates the Homes not Bombs non-violent direct action network. He has worked closely with the targets of Canadian and U.S. “national security” profiling for many years.