“A lot of Filipinos and others are silent in their jobs….They are scared that if they do something for change, they will be deported….They feel held at the blade between life and death.”

The migrant worker who spoke these words, quoted in Fight Back: Workplace Justice for Immigrants, is talking about an experience that is becoming increasingly common in Canada. Workers from countries across the global South are seeking decent work in Canada, yet when they arrive here, they often find themselves chained to the bottom of the labour market, and reluctant to speak out for fear of extradition. Fight Back, written by five politically engaged academics who work with the Montreal-based Immigrant Workers’ Centre (IWC), helps to counter the exploitation of migrant workers by documenting their struggles.

The scope of Fight Back is broad, drawing on interviews with about 50 migrant workers, including both those who come to Canada through established channels such as the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, and so-called “illegals,” who must navigate workplace challenges in constant fear of being deported.

While certain challenges that migrant workers face — racism, for instance — are shared by many Canadians, deportation is a unique threat that serves to keep migrant workers from asserting their rights and demanding equal treatment. On a daily basis, workers — including visa-holding contract workers — run the risk of being deported to their home countries if labelled as troublemakers by their employers.

Migrant workers are often socially isolated: those who come to Canada through the Live-in Caregiver Program, for instance, are required by contract to live in their employer’s private home; the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) requires that workers live on-farm in dorm-style accommodations provided by the employer.

The publication of Fight Back is timely. The Harper government recently expanded the Temporary Foreign Worker Program through the passage of Bill C-50, despite the objections of groups like the Alberta Federation of Labour, which called the program “part of a deliberate effort to drive down wages and working conditions and to bypass unionized Canadian workers.” As noted in Fight Back, this immigration bill has streamlined the flow of guest workers from countries like Guatemala into sectors ranging from fast food to the tar sands.

The explosive growth of this migrant workforce in recent years, Fight Back reminds us, is a direct consequence of neoliberal policy and corporate malfeasance, at home and abroad. The North American Free Trade Agreement, for instance, has opened the Mexican market to cheap, subsidized U.S. corn while allowing transnational agri-corporations to purchase enormous swaths of Mexican land. This results in the displacement of rural peasants, who must then pursue work in exploitative maquiladoras or look further north towards jobs in the U.S. and Canada. Similarly, the destruction caused by Canadian mining corporations in countries like the Philippines and Guatemala push people off of the land, further enlarging the migrant labour force.

Governments of countries that provide migrant workforces, in turn, encourage migration in order to mitigate poverty crises at home through monies remitted to the families of workers. Fight Back emphasizes that these family obligations frequently bind workers to their jobs, in relations that are often gendered. As one migrant worker states, “Especially the Filipino women, most of us believe that sacrificing is the way to get to heaven.”

The pressures to conform to Canada’s job market often result in what the authors call “learning in reverse,” a key concept in Fight Back. This process teaches immigrants to “accept and accommodate harsh economic conditions…to deny their social status and education, to hide their “over-qualification” and adapt to this bottom of the labour market.” Trained nurses find that their foreign credentials are worth little; as domestic workers, they receive a low level of compensation while providing a high standard of care.

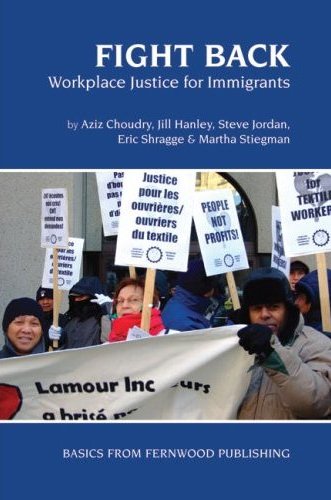

But migrant workers also learn to resist, and Fight Back draws on the experiences of migrant workers to demonstrate the process of transgressive learning. For example, Maria, an immigrant from El Salvador, demanded respect from her employer — L’amour, a garment manufacturer headquartered in Montreal — who was harassing employees and demanding higher production quotas. While the L’amour company union discouraged her from taking action, the IWC helped Maria to file a successful complaint with the provincial labour standards bureau.

Fight Back emphasizes that transgressive learning and active resistance require community support: “Individuals that did eventually take action always did so with the support of others, who provided them with information and other resources to help them in a dispute with an employer.” Key organizations offering this kind of support in Quebec include PINAY, a non-profit organization of Filipina women, and the Centre d’appui pour les travailleurs agricole which works with the United Food and Commercial Workers to empower migrant farm workers in Quebec.

The authors argue that although these organizations are connected to the labour movement at large, global dynamics like the widespread relocation of industry to cheaper sites of production abroad have “in some cases fueled exclusionary or racist practices within unions towards immigrants, rather than solidarity or support.” Fight Back calls for unions to embrace new models of organizing capable of introducing “a community approach to traditional unionization” that would benefit immigrants and other low-wage workers.

Fight Back reveals an alarming trend in Canada’s political economy: the emergence of what the authors describe as “a new underclass of immigrant labour” that risks undermining the rights of all workers as it becomes easier to evade and weaken organized labour through expanding temporary foreign worker programs. Anyone who desires to live in a fair society should take notice.–Dave Koch

This review first appeared in Briarpatch Magazine.