Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

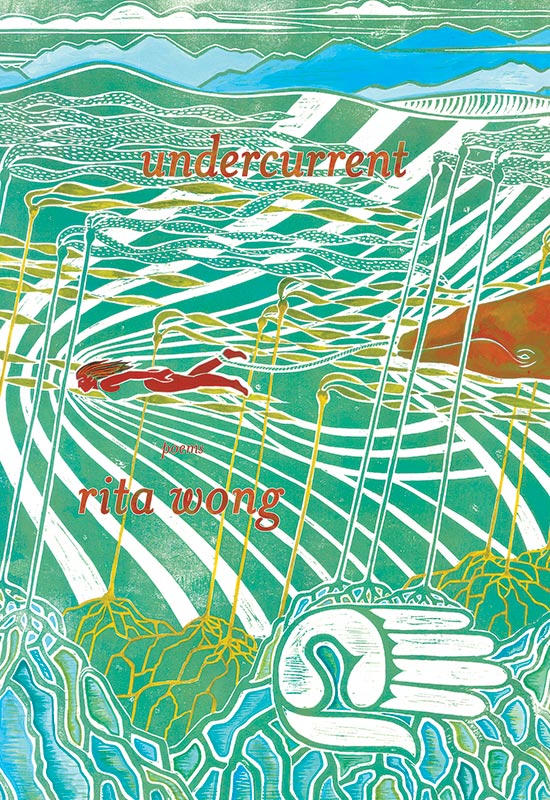

“let our societies be revived as watersheds” writes Rita Wong in the poem “Declaration of Intent” in undercurrent, her third book-length work of poetry. “not tar but tears,” the poem continues, “e inserts a listening, witnessing, quickening eye.”

The poem — and the book — advocates for an affective and immersive engagement with the water systems that support life, a view through water towards a response to the uneven colonial control of resources by state and industry, and the uneven damages to individuals and communities.

The poems in this collection propose a poetics and politics of water that acknowledges the ubiquity of water issues — from when we flush to the waste waters of industry. The personal is universal in one’s contact with water, and Wong’s poetry puts itself at the service of water and those who fight to maintain its sovereignty and safety.

While reading undercurrent for the first time, I moved from Vancouver back to Ontario, where I stayed in my childhood home in Bright’s Grove on the shores of Lake Huron, and finally moved into St. Catharines on Lake Ontario. My partner and I left B.C. during a period of prolonged drought, in which wildfires filled the city with smoke, and, at the time of writing, continue to threaten inland communities.

The need for water has ushered in municipal water restrictions, and raised awareness of and resistance to the province’s dealings with Nestlé over prices and rights to groundwater for bottling. Near Bright’s Grove, Ontario the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, who have seen the so-called Chemical Valley’s petrochemical industry totally surround their community, continues its fight against state and corporate environmental racism for proper air and water testing.

I list these personal proximities and interactions with the politics of water because this is what Wong’s book prompts: an attention to the ways in which water rights, sovereignty and purity affect ourselves and those around us.

It also highlights a complicity with the methods by which water is controlled and employed unequally under capitalist and colonial power: “calm in chronic pollution, kindred water is a secret player reflecting industrial flaws back to us” (“bisphenol ache”).

Through an attention to environment in these poems the calm of consumption becomes unsettled in its reflection in water and water poetics.

The poem “immersed” lists many pollutants, life forms, and experiences brought together through water systems:

immersed in chlorinated water

immersed in formaldehyde off-gas

immersed in car exhaust

immersed in the oxygen produced by oceanic plankton

The poem moves between ubiquitous contaminants and the life-support of water in a meditative mode that lulls with repetition, but unsettles in its reflective criticism.

immersed in carbon dioxide

immersed in the colonial present

immersed in loonsong

immersed in endocrine disrupting dust

immersed in the smell of the ocean

As “carbon dioxide” finds a connective consonance in “the colonial present” and is then disrupted by the calm of “loonsong,” which in turn is affected by “endocrine disrupting dust” the list ebbs and flows in waves of critical attention.

Water may be polluted and made hazardous through capitalist management, but it also presents a subversive undercurrent that, as the book’s epigraph by Bruce Lee suggests, is “formless, shapeless,” but can “flow, or it can crash.” So too does poetry in this collection. It flows between forms, allowing the language to shape an embedded critique.

undercurrent‘s most noticeable formal trait is the intermittent printed waves that occupy the bottom of the page throughout the collection in which quotes appear. These quotes play a role similar to epigraphs (which the book also employs occasionally), but extend beyond the poem to give the sense that this poetry arises from a dialogue with other authors, other words.

Below “declaration of intent,” the words of Wes Nahanee, from the Squamish Nation, flow: “water is unstoppable.” Rather than using the words as epigraphs to directly situate the concerns or contexts of the poem, these aquatic footnotes give the sense of an engaged poetics that seeks dialogue and response.

This technique is similar in some ways to Wong’s use of marginalia in her previous collection, forage, in which handwritten quotes border many of the poems. Both techniques foreground the dialogic activity of poetry, and the poems become conversations with others that subvert the logics of an “I”-based lyric.

undercurrent‘s poetic forms include recurring sections of prose spoken by a “we”:

Who are we? We are beings who need clean water in order to live a life of dignity, joy and good relation. Maybe you are part of “us” without even knowing you are. Maybe we are the ones who are too often taken for granted or ignored, the quiet witnesses to atrocities, greed, mean-spirited hierarchies, hostages of capitalism.

The immersive pronouns flow in a repetitive, though always critical, attempt to sum up the impossible complexities of water’s reach. “We” are complicit, “we” are victims, and Wong’s poetics here makes room for the seemingly contradictory relations that water enacts.

Such fluidity, though, does not preclude a crashing response in these poems: “Dripping & and spitting, we rise.” And later: “we are undercurrent.” Such sections sometimes arise, in Wong’s collection, from documentary prose paragraphs (also marked by italics), in which the poet’s experiences as an environmental activist and ally are described.

As with the undercurrent of quotation, these sections highlight the poems’ political focus and service to a cause. This resists a decadent logic that would see poems function as isolated experience, and instead instigates a poetics that, like water, flows beyond its boundaries, always towards the rivers, lakes, and oceans that support life.

One such documentary section describes the Healing Walk for the Tar Sands, in which the poet walked with the first nations communities affected by Alberta’s tar sand and other activists, giving witness to “the brutality that has been normalized through massive industry.”

At times, the poetry becomes an almost overwhelming immersion in the language of contamination:

broken earth torn hole caterpillar

rubble silent rain atrazine spring

dirt dirge drip naphthalene

benzene formaldehyde xylene

atrazine puddle DDT remnants

tree roots tree corpse petrified

Here, the poem “motherboard” presents a language and water contaminated, refusing all but a few semantic connections. Meaning instead bioaccumulates in the poem. The aural resonances of the chemical “-ine”s and “-ene”s slow reading, which allows the surrounding familiar words to take weight.

Wong highlights the histories and biases carried in the familiar as we are “immersed in English” (“immersed”), and highlights that as much as the industrial contaminants sound unfamiliar, so too is English a colonial linguistic contaminant that erases the languages of the land’s first peoples.

Wong returns these poems of water to aboriginal languages.

The poem “immersed” ends with the line, “immersed in q’élesxw.” “Q’élesxw” is a verb meaning “to return” and “give back” in the Halq’eméylem language of the Stó:lō group of first nations peoples who inhabit B.C.’s Fraser Valley (www.firstvoices.ca).

Further on in undercurrent, a poem entitled “q’élesxw” appears, in which “the city paved over with cement english cracks open Halq’eméylem springs up.” The poem replaces the familiar language and artifices of the city and its dominant language with the traditional, ancestral words of the Fraser Valley. In this the poems gesture towards a hopeful return to the immersed, and, for many, forgotten, language of the stó:lō — in English: “water.”

Through a poetics of “q’élesxw” and water, the poetry of Wong’s collection resists indulging in despair, and instead it offers cracks in capitalism, industry, English and the language of colonialism in which alternative narratives and social relations may be written and imagined.

The collection concludes with “epilogue: letter sent back in time from 2115.” The prose poem offers a future history in which “spontaneous compassion sprouts in the cracks of collapsing systems,” and “people…watch water’s journey the way they used to watch the dow jones.”

The poem describes a speculative fiction that offers an alternative to capitalist pollution and linguistic contaminants, and propels the poetics of water beyond despair and inaction.

In this way, undercurrent offers poetry that is engaged in critical hope for the power in the watersheds of language and political resistance.

This review originally appeared on The Rusty Toque and is reprinted with permission.

Andrew McEwan the author of repeater, a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Award, and the chapbooks Input / Output, This Book is Depressing, and, Conditional. His work has recently appeared in Canadian Literature, Lemon Hound, Poetry is Dead, The Puritan, and Avant-Canada: More Useful Knowledge. His next book, If pressed, is forthcoming from BookThug.