In his remarkable 2009 text, Cruising Utopia, José Esteban Muñoz fixates on the ways in which queer bodies exist outside of and subvert what he calls “straight time.” Straight time, for Muñoz, is what tells queers that “there is no future but the here and now of our everyday life.” It grounds the fragmentation, suppression, and elision of queer histories, and denies futurity to those not counted under the rubric of a “reproductive majoritarian heterosexuality.”

Straight time has, as it were, no time for queers beyond the present, a moment that disappears the instant we name it as such. The present is always already gone. Without the powerful synchronicity between body, biological reproduction, and futurity that characterizes a heteronormative way of being, what is (or what can be) the future be for queers?

This is why, in Muñoz’ estimation, it is essential that we ask not just what but when a queer body is; what it’s been, what it might yet become. To challenge time, tense and chronology is to oppose the operation of straight time and its ability to narrativize queer bodies out of existence.

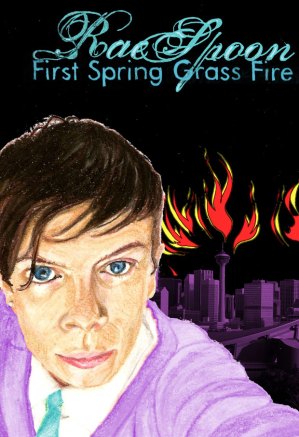

This question of the when of queerness is at the heart of transgender electronic musician Rae Spoon’s remarkable debut novel, First Spring Grass Fire. In a direct, crystalline voice, Spoon unfolds the story of growing up Pentecostal and queer in Calgary, Alberta.

An intensely personal, darkly funny, and stunningly honest book, First Spring teeters on the border between fiction and memoir, oscillating between a ‘real’ past and an alternative history that might have been.

At a meager 137 pages. First Spring is, at first blush, a modest read. Carved up into 24 slim chapters more accurately described as vignettes, it wheels erratically through memories of Billy Graham prayer rallies, the horror of gym class dance lessons, Pentecostal guilt, drugs, music and suburban misery, rarely stopping to catch it’s breath.

Even the death of an infant brother receives little more than a few pages of direct attention before Spoon’s narrator (with whom they share a first name) veers off course toward their father’s schizophrenia, nightmares about wedding dresses, and the Calgary Stampede.

[As an aside: Spoon offers what is perhaps the most accurate description of the Calgary Stampede ever put to paper: “the city becomes a sea of new white cowboy hats and denim worn by office workers who have probably never been on a farm. You can see them in the evening sauntering around town drunk with little bits of straw stuck on their outfits from the bales of hay that are trucked in for the occasion.”]

Not surprisingly, in the midst of such rapid narrative swings, tenses often fail. It is not at all uncommon for First Spring to condense past, present and future into a single paragraph with little warning or signal.

As Spoon’s narrator recalls, for example, playing along to Wheel of Fortune with their grandparents, they operate exclusively in the past tense, calling up their time living in a tiny Calgary basement as a concrete memory, now completed: “my uncle and I would gang up on my grandmother and tease her.” Without warning, however, the chapter closes with a shift to the present tense: “She always beats me at scrabble and can play the piano, organ and accordion by ear.”

A relationship that only moments prior seemed resigned to the already-disintegrating space of memory is suddenly very much alive. By traversing the same temporal boundaries thrown into question by the book’s refusal to side either with fiction or biography, Spoon continually manages to excavate what seems lost. Where a ‘straight time’ narrative might deny the speaker’s future by forgetting their past, Spoon’s stuttering timeline does just the opposite: giving hope that a fading relation might endure by recovering what is no longer.—Tyler Morgenstern

Tyler Morgenstern is a Vancouver writer, communication specialist, and social change advocate.

This review was first published on Art Threat.