If the novel was the distinctive art form of the 19th century and cinema that of the 20th, in the 21st century, either the graphic novel or the online podcast seem likely to fill that role. Art Spiegelman’s brilliant Maus, published as a serial between 1980 and 1991, used comic book tropes to tell an ultimately serious story about the author’s father and his Holocaust experiences. In 1992 Maus was the first graphic novel to receive a Pulitzer Prize.

The new genre has many impressive Canadian practitioners. In 2019, Vancouver author Wade Compton and illustrator April dela Noche Milne published The Blue Road, which uses the graphic novel format to tell a story about immigrant experience. Maritime author Kate Beaton used a similar format to explore the life of a young woman working in the Alberta tar sands, creating a document that blends class, gender, and environmental damage into the spectacularly successful word and graphics bundle, Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands.

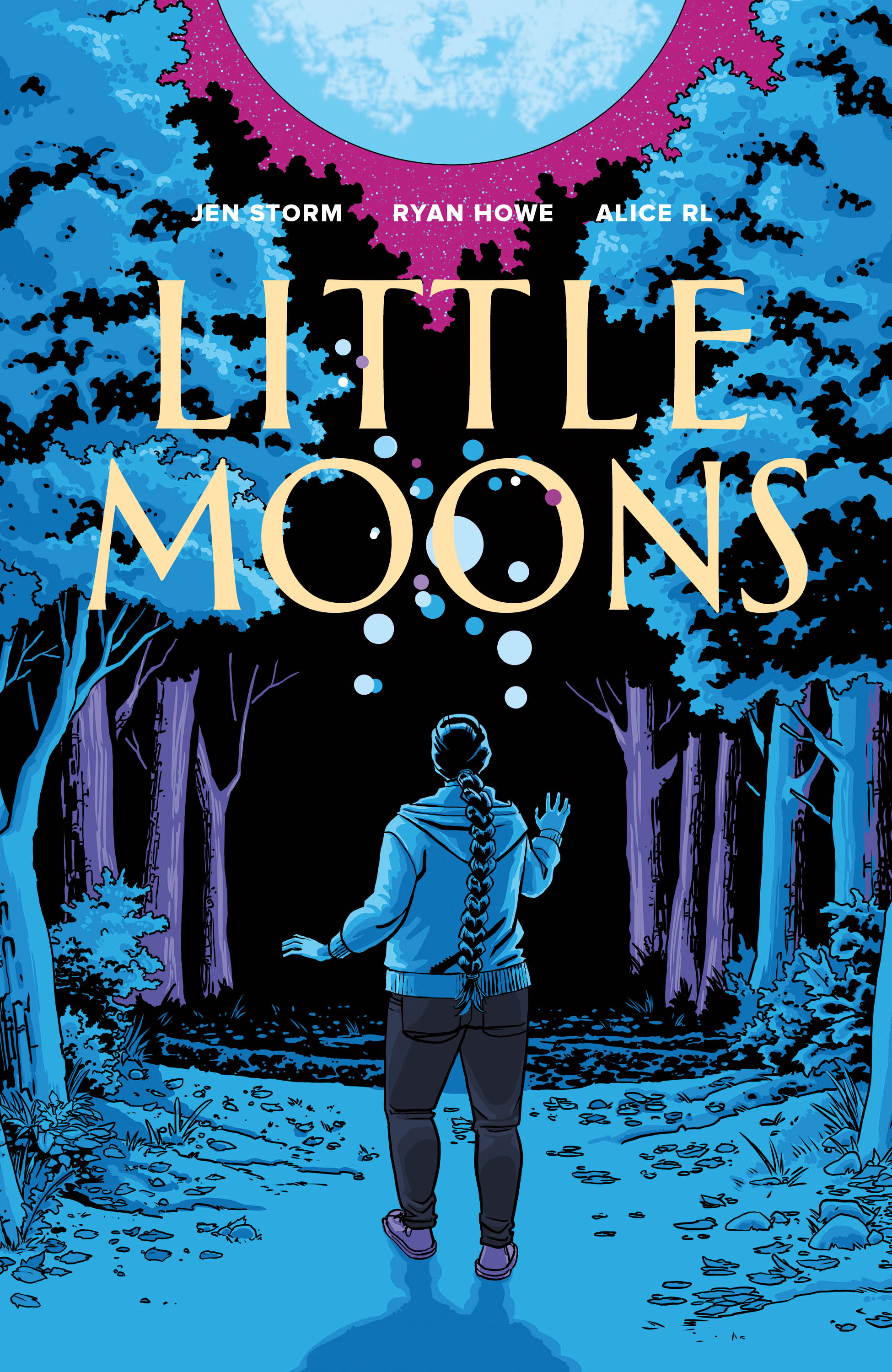

Little Moons, by Jen Storm, Ryan Howe, Nickolej Villiger and Alice RL is a Canadian graphic novel that tackles the heart-scalding realities of the brutal femicide waged against Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people in this country. The author, Jen Storm, writes from searing personal experience. A member of the Couchiching First Nation in Northwest Ontario, Storm had a family member go missing, and later learned her loved one had been found dead. She says in an afterword to the book that “When a loved one goes missing, some families never get answers or closure, which I felt was important to show in Little Moons.”

And show it she does. Little Moons goes beyond the cold (and often incomplete due to faulty reporting) numbers to give the reader a single family scoured by grief and untouched by “closure,” as they deal with the loss of a beloved sister and daughter. We meet Chelsea, the young woman who goes missing after school, her sister Reanna, the girls’ mother, grandmother, father, and little brother Theo, and see them responding over a year to Chelsea’s disappearance.

Despite desperate searches by family and community members, Chelsea is not found. The closest the searchers come is her bag, buried on the edge of the forest. The family members are left to mourn the death this find suggests, each in their own way. Chelsea’s mother flees to the city and an attempt to find solace in assimilation and a new non-Indigenous lover. Reanna and her father turn to ceremony for some comfort, and Theo senses his lost sister as a spirit, a “little moon.”

All of this poignant, nuanced narrative is conveyed in spare, often dark images and in terse, believable dialogue bubbles. We are denied the false comfort so often conveyed through sentimental closure or all too perfect victim figures.

This remarkable book centers on the experience of one family in all its human complexity and imperfection, and its power as art is deepened by that complexity. This book has both aesthetic and political power, reminding us of all of the horrors that have been inflicted on Indigenous peoples during colonization and summoning us all, particularly those of us who have benefited, no matter how unwillingly, from the colonial project, to find an adequate response.

We hear a lot these days, often in repellently self-serving government announcements, about “Truth and Reconciliation” even as many of the actions demanded by the inquiry into the disappearance death of women and girls go unfulfilled and far too many Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit folk remain vulnerable to predators who stalk them from the Highway of Tears to the dark streets of our big cities.

But as our Indigenous sisters and brothers remind us, truth comes before reconciliation. We should be listening to them, and this tough, tender, and beautiful book delivers some of the truth we all need to face.