I was determined to see the sun setting over the sea of Jaffa. I made it. The air was dry and fresh. Lower hills spread below me like a crumpled sheet of blue velvet with the hamlets huddled in its folds. One hill interlocked with another in a slow, gentle, slope down to the coastal plain and ultimately the sea. I was standing on the highest hill before the drop. I continued to take in the view as the last rays of the sun were making their final slow journey dropping gently into the horizon, which I could barely make out in the haze…I was unaware that this would be the last time I would be able to stand here on an empty hill. Shortly afterward the Israeli authorities expropriated the land and used it to build the settlement of Dolev.

When I look back now at those years in the eighties when I could walk without restraint, I feel gratified to have used that freedom…There was one walk that I had always planned which to my great regret I never got around to taking. It would start from the west of Ramallah, through Beitunia to Wadi El Mahkwm, passing north of Beit ‘Ur…the path continues through the central hills, emerging in the coastal plain and on to the blue Mediterranean Sea. I had planned this walk so carefully. Now with the settlements and the Separation Wall it was impossible. (p. 65-66)

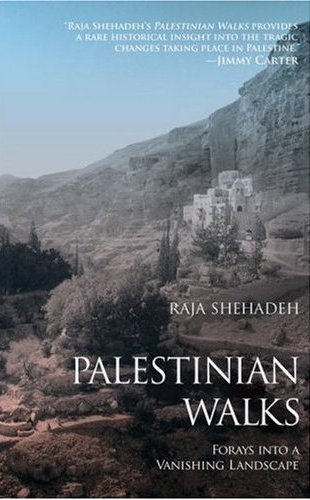

The writer and human rights lawyer Raja Shehadeh was born in Ramallah. Palestinian Walks:Forays into a Vanishing Landscape, his memoir of walking in the hills around his home, spans over a quarter-century of a life spent observing the unique character and ecology of the land, as well as the impact of its inexorable conquest and occupation. Yet his emphasis is on the land as a living entity, since he tells us: “I like to think of my relationship to the land, where I have always lived, as immediate and not experienced through the veil of words written about it, which are often replete with distortions.”

Shehadeh first heard of the Palestinian custom of walking, the sarha, in childhood, in stories about his grandfather, a judge whose summer holidays were devoted not to big city pursuits but to a more slow-paced rural pleasure: “A man going on a sarha wanders aimlessly, not restricted by time and place, going where his spirit takes him to nourish his soul and rejuvenate himself…Going on a sarha implies letting go. It is a drug-free high, Palestinian-style.”

Sometimes walking with a friend or with his wife Penny, often setting off across the hills alone, Shehadeh appears to be the sole custodian of the sarha custom after he begins his law practice in Ramallah. On one of his own earliest sarhat in the splendid hills in springtime, 1978, Shehadeh discovered the qasr, a simple house built entirely of stones fitted together by hand, belonging to his grandfather’s cousin, Abu Ameen, whose life in the early 20th century as a rural cultivator and stonemason contrasted sharply with his more worldly cousins who sought higher education and professions in the cities. It was Abu Ameen who spent six months of every year in his qasr, sleeping rough and walking the hills; it was the aging Abu Ameen’s house in Ramallah to which the city cousin, Shehadeh’s grandfather Saleem, fled with his family when they were forced out of Jaffa in 1948.

As the years pass, Shehadeh’s preferred mental health habit is curtailed by rapid settlement expansion. Environmental wreckage goes with political conquest as the hilltops surrounding Ramallah are bulldozed and flattened for the creation of Jewish-only housing settlements, a process the Israeli government first embarked upon in the late 1970s through systemic changes in the law intended to facilitate land expropriation.

As a young lawyer in Ramallah, Shehadeh closely followed these developments, arguing against cases of land annexation in the Israeli courts, in the belief that a well-planned legal strategy would bring justice to Palestinian landowners.

It was a belief he held to persistently, but with little success and increasing scepticism, until the signing of the Oslo accords in September of 1993. He could see plainly then what so many denied, that the infamous handshake over which Bill Clinton presided in Washington was a complete capitulation by Yasser Arafat’s regime to continued building of settlements and the bypass roads, checkpoints, and daily restrictions on Palestinians’ lives. Shehadeh had every reason to give up the struggle. Yet despite his disillusionment, as his friend Edward Said noted in 1996, Raja Shehadeh never left his home in Ramallah; never stopped walking, reflecting, remembering and writing.

Shehadeh’s prose, like his walks, constitutes the act of making peace — exulting in the rich beauty of the land, remembering its past, witnessing its changes, and rescuing it, even if only for an hour or a day, from all the political anxieties and religious desires that others project onto it. To walk is to move in the simplest possible way, without weapons or aggressive postures; leaving behind high-tech gadgets that distract from the here and now. The gaze of the walker is open, seeking not to impose its vision on the world but to take the world in: to shed even the layers of name and nation that can get in the way of seeing clearly. Against the hills, a walking companion’s ringing cell phone is an embarrassment, and the gun held at the settler’s side is a disturbing intruder. The settler himself — extraordinarily — is not. Not in this instance.

The most impressive feat of Palestinian Walks is Shehadeh’s final chapter, wherein he imagines an encounter with a Jewish settler, a young man who seeks the same unhindered quiet and reflection in the hills one afternoon. The conversation they have is a painful and fully human exchange of tensions and resentments that could only arise between people who have lived their lives within minutes of each other in starkly unequal material conditions. With grave thoughtfulness Shehadeh gives his enemy’s perspective considerable space alongside his own; he pulls off this risky, generous act, despite the fact that it is he, and not the settler, who must endure such routine humiliations as pleading with a soldier imposing a curfew to be allowed to return to his house at night.

Palestinian Walks, awarded the George Orwell Book Prize in 2008, is a magisterial demonstration of grace under intolerable pressure. It ought to be a standard text in every conflict resolution class on the planet:

“He [the young Jewish settler] must have been brought up on the fundamental untruth that his home was built on land that belonged exclusively to his people, even though it lay in the vicinity of Ramallah. He would not have been told that it was expropriated from those Palestinians living a couple miles away. Yet despite the myths that make up his worldview, how could I claim that my love of these hills cancels out his? And what would this recognition mean to both our future and that of our respective countries?”

Shehadeh’s sarha does more than strip away fixed ideologies and perspectives; it is a powerful act of positive resistance; a contribution towards a just and humane future. A footpath, once forged, salvages the barb-wired landscape from its otherwise bleak fate as a political abstraction or religious symbol, affirming it to be first a real, inhabitable place. Because Raja Shehadeh writes so vividly of his walk in a valley overlooking a field of blooming flax beneath an olive grove, the children now stuck in refugee camps and military checkpoints might more easily imagine themselves retracing his steps, unimpeded; perhaps sketchbooks and pencils in their hands, perhaps walnuts and dried figs in their pockets: “It was good to dream of this…It was not uncommon for me to think of crazy schemes while walking in these hills.”–Rahat Kurd

Rahat Kurd walks and writes in Vancouver, on Coast Salish land.