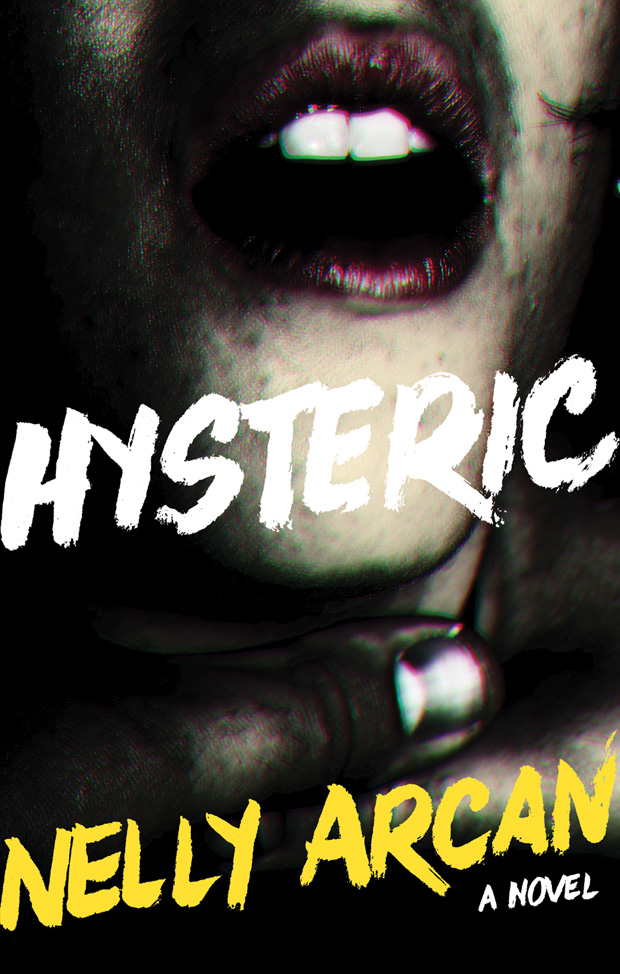

The narrator of Hysteric, Quebecoise author Nelly Arcan’s recently translated second novel, is — like her creator — a young Plateau Mont-Royal writer named Nelly whose debut novel about her years as a prostitute was an international success. Having sworn at age 15 to end her life at 30, Nelly tells us early in the text that “something within me has always been absent.”

But the gaze of a nameless lover, a young freelance journalist with a penchant for cyberporn, infuses her with a fragile vitality; Nelly, at 29, meets him at a techno party in a bar aptly called Nova.

Increasingly “hysterical” as the eight-month affair begins to explode, Nelly acknowledges her madness, linking it to her conviction that she was “meant to remain invisible.”

Hysteric is framed as a long suicide note written by the narrator to her former lover, though one of its most enigmatic phrases is that “this letter…really isn’t addressed to you.” The work is uniquely structured, relating the love story in the broadest terms right away, then spiralling slowly into the details.

Both the hint at an unknown addressee and the circular quality of the narrative, which makes it seem an inquiry into the core of the relationship, suggest authorial distance.

Though Nelly, like Arcan’s other protagonists, closely resembles the author (Arcan committed suicide in 2009), it is essential to keep in mind that she exists within the realm of fiction. Arcan (on Radio-Canada’s talk show Tout le monde en parle) tried to underscore this distinction between fiction, however autobiographical, and fact, saying that a statement she’d made about undesirable women being “larvae” in an interview about her first book Whore must be understood within the “system” of the book — the world that creates the whore.

Similarly, the protagonist Nelly’s theorizing about women and men in Hysteric must be seen as part of its nihilistic architecture. Nelly refers to herself as a “nobody,” in spite of her success, while her lover is a “giant” with a “commander’s voice.”

The two cannot escape their pre-set roles: the lover uses her shamelessly, while Nelly grows increasingly frenzied about other women.

In this universe, where sexual love either ends in the “boredom … of procreation” or dies, men are narcissistic, frivolous and indifferent, favoured by a reproductive process dependent on their pleasure, while women are “solemn,” “looked downward” and howl in despair at their sexual abandonment.

Whatever one thinks of the truth of this “system,” it is captured by Arcan with rare lyricism and power. This is partly because it seems to represent something larger than itself.

From the beginning, the text connects the religious past and the pornographic present; the two dominant figures in Nelly’s life are her dead, devoutly Catholic grandfather, and her lover, who writes like a prostitute’s “client,” and often requires the help of the Internet to become aroused.

Arcan draws a parallel between the grandfather’s God, who “retreated very far into the sky” after he created man, and the lover’s inability to desire the woman who is in his bed every day. The trio of grandfather, lover and Nelly engage in a torturous, yet inescapable conversation, within Nelly’s “hysterical” mind, about the elusiveness of the infinite.

It’s an old theme, and there are echoes of a medieval sensibility when Nelly points out to her lover (who responds to her jealousy with accusations about her own past) “that repentant whores often have a second life as nuns.” Arcan’s use of the word ‘whore’ has a spiritual dimension in places: It was a wish to be “open,” Nelly suggests, that made her turn to whoring. Her desire for surrender recalls the rapturous self-abnegation of mystic poets.

At the height of the affair, Nelly says “you brought me to the ground zero of autonomy”, and at her last meeting with her lover she is “nothing but openness to you.” Yet she knows by the end that the lover’s self-obsession is as impenetrable as a computer screen.

To whom, then, is her suicide note really addressed?

Though she concedes she is “part of my grandfather’s lineage,” Nelly cannot, like him, look only at God; she has “many of his things” but not his faith. She knows that “the soul does not exist,” and the comedy of love she must play out seems a rite no one believes in anymore. She can only speak into the void of her relationship.

There is no triumph here, no redemption. But Arcan’s text is a heroic examination of the suffering of contemporaneity, expressed with a purity of longing that transfigures the “corruption” of the protagonist’s existence.

By the end, we think Nelly’s madness less her own than the consequence of seeking the absolute in a world that reduces love to fashion-magazine formulae; we recognize the “absence” within her as our own.

Aparna Sanyal is a writer and editor living in Toronto.