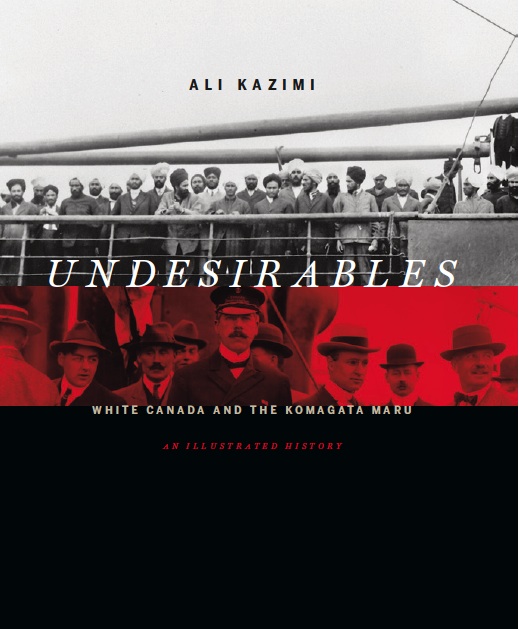

As Parliament passes sweeping, repressive immigration legislation, Toronto filmmaker Ali Kazimi’s timely book, Undesirables, is a welcome and necessary contribution that should be required reading not only for Jason Kenney and his cohorts, but also those good-hearted folks who claim the new law violates Canada’s mythic “humanitarian traditions.”

The Komagata Maru was a shipload of South Asian immigrants forced to dock a half mile off the B.C. coast for two months in 1914 as a battle to determine whether they could land played out in the media, the courts, on the docks and in a variety of communities. Denied access to counsel, blockaded from receiving food and water, demonized in the press, and eventually forced to leave when a Canadian court ruled that race could be a grounds for excluding newcomers, their struggle was a signature moment reflecting an ingrained xenophobia that undergirds contemporary Canadian policies.

The book is visually stunning, thorough and wholly accessible in its historical, political and social presentation. Kazimi, whose documentary Continuous Journey also portrayed this period, outlines the extent to which Canada was built as “a white man’s country,” and how specific communities (largely South Asian, Chinese and African American) were systematically excluded from Canada. He also illustrates how limited numbers from these communities, in a mirror to today’s wretched treatment of temporary foreign workers, were allowed in to Canada to perform menial labour, but had impossible obstacles thrown in the way of permanent residence, much less family reunification.

Importantly, he documents the wretched conditions in countries under British colonial control (from political repression to easily preventable famine and disease) that resulted in the urgent desire to emigrate not simply for a better life, but to save one’s life. Indeed, many onboard the Komagata Maru were Sikhs, who paid a huge price in the struggle against British colonialism, a fact that Kazimi notes is rarely acknowledged.

As hundreds of thousands of white Europeans entered Canada in the first decades of the 20th century (on average, 200,000 annually from 1908 to 1914), a series of racist measures were imposed designed to cut off the flow of immigration from countries like India and China. Indeed, from 1907-1910, fewer than 3,000 South Asians were admitted, and only five in 1910-11. This was the era of the Chinese Head Tax, as well as specious medical examinations that turned certain classes of immigrants away for common and non-threatening afflictions, and the requirement that certain immigrants possess the then princely sum of $200 before gaining entry to Canada.

While “the yellow peril” and other racist headlines dominated the papers, racism was easily adaptable to prevailing political winds. Notably, after Britain formed an imperial alliance with Japan, Japanese men were allowed to bring family members to Canada, but Chinese and South Asians were not.

“That Canada must remain a white man’s country is seen necessary on moral and political grounds,” wrote future Prime Minister Mackenzie King in a 1908 report that articulated the reasons for imposing a “continuous journey” order in council that would remain for 40 years, essentially barring South Asians from entering Canada unless they came directly from India. Kazimi show that, nonetheless, British authorities were concerned about the need to soft pedal some of Canada’s racist legislation so as not to inflame tensions in its colonies: after all, this was a time of growing resistance to British repression, and not all individuals who were British subjects took kindly to discriminatory treatment.

Kazimi’s study also does a great service by examining the resistance of targeted communities, who formed self-help and self-defence leagues, raised money for the folks aboard the stranded ship, engaged legal assistance, and produced their own newspapers. Part of that resistance was the Komagata Maru itself, whose journey was a publicly announced challenge to the continuous journey provisions: it picked up passengers from a series of overseas ports on the way to Canada.

With no small sense of irony, once a test case for a Komagata Maru passenger got to court, government lawyers successfully argued that since First Nations had limited rights as British subjects, Canada actually had the power to restrict rights of other British subjects based on race. As Kazimi sadly concludes, “the colonization of Canada and the subjugation of its aboriginal inhabitants was presented as a legitimate precedent for denying South Asians their rights.”

By the time the ship returned to India, the stench of alleged subversion had been imposed on the passengers by British colonialists, and 21 of them were shot down by British troops upon their arrival, with many more arrested.

Kazimi sees the Komagata Maru as a transformative moment for Canada, occupied India, and the rest of the British empire, but cautions against seeing this as an isolated instance. Rather, it was one of many moments in a long history that continues to this day. His superb ability to connect past and present policies both shows the parallels and explains the extent to which the “white man’s country” theme threatens to remain forever stitched into the Maple Leaf.—Matthew Behrens

Matthew Behrens is a rabble.ca columnist and a regular contributor to the book lounge.

We’ve extended our amazing gift offer of a free magazine subscription until Friday, July 13…become a rabble.ca today!