Teen fiction, like the wildly popular Gossip Girl series, excerpted above, often reads more like a Brett Easton Ellis novel than a Judy Blume, allowing readers to spy on the lives of wealthy teens with unlimited credit card access and romanticized eating disorders. In fact, according to The New York Times, Gossip Girl and contemporaries Clique, and A-List have collectively sold 3.5 million copies.

However, being taught as a child to never judge a book by its cover (or a popular spin-off television series based on it) I stopped by the library and checked out Gossip Girl, the first book in Cecily von Ziegesar’s popular series, hoping that my preconceptions might be wrong.

Like I expected, Gossip Girl presents a world of plastic surgery, bulimia and sex, where female sexuality is equated to punishment and ridicule (though chastity brings a similar fate). Human relationships take the back burner to female characters’ preoccupation with fashion, thinness and wealth. Here, brand names are as reoccurring as the characters themselves. Should I be surprised? Thankfully, some Canadian publishers are offering alternatives to these tales of hyper-consumptive youth, perfect for progressive teen readers.

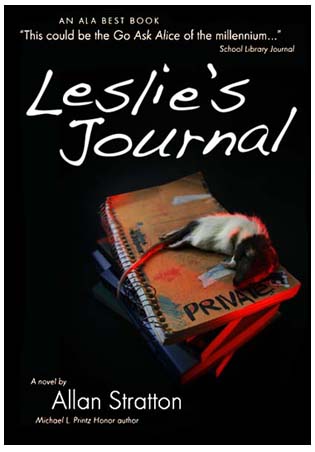

Allan Stratton’s book Leslie’s Journal, which was re-released earlier this fall by Annick Press, tackles difficult issues, most notably abuse – both mental and physical. This award-winning book was originally published in 2000, and has been updated to include instances of cyberbullying and advances in technology, such as Facebook.

Leslie, Stratton’s 15-year-old protagonist, is rough around the edges. She has a rocky relationship with her parents, especially after their divorce, and she spends almost as much time in the principal’s office as she does in class. A lonely and rebellious character, Leslie meets the mysterious Jason, a new student who charms her instantly. That is until the relationship turns sexually abusive and Jason insists on monitoring her every move, even buying her a cell phone equipped with a GPS chip.

Addressing the unkind reality of sexual violence, at first Leslie defends Jason, covering her bruises with excuses. Fearing victim-blaming, Leslie worries that nobody will believe her if she comes forward about the abuse, especially because she’s cultivated a rebellious reputation and because she does not share the same socio-economic status as Jason’s wealthy family.

Some of Stratton’s imagery seems outdated, possibly remnants of the book’s previous version. For example, Jason is "terminally cool," with his black leather jacket and shades. Despite this odd fumble, Stratton has created a strong character in Leslie, one which young readers will easily relate, especially as it becomes increasingly obvious that Leslie is likable beneath her rebellious attitude.

Similar to the 1970s cult classic Go Ask Alice, Leslie’s Journal is told exclusively through journal entries, which Leslie is required to write, with a promise of anonymity, in Ms. Graham’s English class. In its pages, Leslie tackles issues of rape, blackmail, sex and manipulation, with great naivety and honesty.

Also using an approach similar to Go Ask Alice is The Saver by Edeet Ravel, which is a 2008 release from Groundwood Books. Instead of writing in a journal, Ravel’s character Fern writes a series of letters to her extraterrestrial imaginary friend, Xanoth. These unique letters are a creative coping mechanism that helps the 17-year-old Native Canadian cope with her mother’s unexpected death. Afraid of entering foster care, Fern decides to keep her mother’s death a secret and support herself, working odd jobs and becoming the caretaker at an apartment building that provides free rent.

Instead of dropping by Manhattan’s trendy shops for the latest designer dresses like the characters in Gossip Girl, Fern visits a number of local dentist offices, hoping to score free toothpaste. She also gets a job at a Lebanese restaurant, which allows her to bring leftovers home to reduce her grocery bill. Fern is the antithesis of the ultra-consumptive teens of Gossip Girl fame. She is thoughtful and lonely, and barely able to pay her bills.

The similarities between Leslie and Fern are abundant, as both struggle to digest their complex lives that seem to distinguish them from their peers, while at the same time dealing with the angst and loneliness that is often associated with coming of age.

Quite different from both Leslie’s Journal and The Saver, Jennica Harper’s book of poetry, What it Feels Like for a Girl, aptly named for a Madonna song, weaves together sexuality and religion to provide a portrait of two 13-year-old girls, who are both intrigued and fearful of their own sexuality. Barely out of her twenties herself, Harper must have vivid memories of her teenage years, because she captures perfectly the contradiction that can define them. "Thirteen is young and old, depending on who you know," she writes, exploring how young women are often expected to simultaneously play the roles of virgin/whore, chaste/sexual, and good girl/bad girl, while facing the scrutiny of both male and female peers. "But what makes girls and boys see sex and want to beat it down?" Harper asks her readers.

Harper writes of young women who still "trust the world, assume it’s all in good fun," learning quickly thatoutward displays of sexuality can harm their reputations. In one of her most memorable lines, Harper writes, "You were learning your private parts, when public, could be weapons," a lesson that Angel, the more precocious of the two girls, embraces.

Harper explores the role of fantasy in the lives of teenage girls, who for the first time are exploring pornography, one another, and their own bodies. "Teenage girls are angels fallen; from the sky to tempt, to torment. They know love, but not how to name it," she writes in the short book, which can easily be read in one sitting.

Each of these three books present characters that are complicated, yet relatable, unlike Gossip Girl‘s vindictive suburbanites, who have more in common with royalty than the average teen. The protagonists in these three books grapple with real problems, creating real solutions, at school, in relationships, and within themselves, resulting in three books that are excellent alternatives to the books dominating the bestsellers list.–Jessica Rose