“Let’s face it. I am troublemaker.” But like most of the terms that might apply to him, Igor Kenk has taken troublemaker to extremes. Infamous in Toronto even before his arrest in 2008, Igor’s name is synonymous with “bike thief” for good reason: in addition to drugs, police searches turned up nearly three thousand bikes in his various storage spaces across the city, some of which were later returned to their rightful owners and many others donated to charity.

The story unraveled and became even weirder-expanding to include Igor’s beautiful Julliard-trained pianist wife, his wild claims inside and outside of court, and his attempts to buy back his bikes from a Cabbagetown non-profit after his 2010 release.

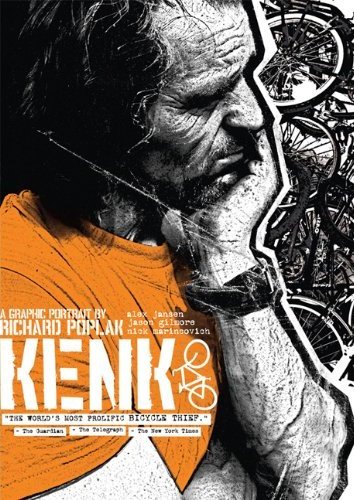

The black and white “graphic portrait” Kenk is similarly layered and complex, teeming with carved-up stills from 30 hours of footage its makers (Alex Jansen, Jason Gilmore and Nick Marinkovich) shot of Igor over 15 months in 2007-2008. Written by Richard Poplak using the interview transcriptions, the text is overlaid on top of these images in a gritty photocopied style taken from 1980s Slovenian ‘zine culture.

Indeed, Kenk is a far more textured and nuanced portrayal than any of the media coverage granted Igor, in which he appeared as super-villain or raving madman (or both). Kenk doesn’t quite dismiss these ready-made labels; it subverts them to fill in the gaps, the layers of grit and grey.

Igor’s muddled, raging ethos dominates every panel, and though his scattered odd jobs — from delivering newspapers to a brief modeling stint — are covered, it’s clear that his sense of himself as a scavenger and entrepreneur form his core beliefs. Eccentricities aside, he also raises a number of points the much-disdained “Public” would rather not think about, in relation to Igor or ourselves.

There is the raging consumerism, for instance, and “vulgar display[s] of purchasing power,” that Igor both scorns and participates in, acquiring discarded junk and anything else he can lay his hands on, while hating the excess, and often hating himself. The book devotes a chapter to his childhood in Slovenia, the “communist shithole” where he began his life as a hoarder: “Back home I was flush with junk because we were poor. And here I’m flush with junk because people are ignorant.”

Running and hustling and philosophizing at full throttle, Igor baldly lists the many follies of the Western world as he sees it, where “everyone has everything,” and “the richer you are the bigger your fuckin eyes become. Even though, in a natural situation, once you are well fed then your interest for food should decrease.” Partly through this speech his partner Jeannie asks if the pants he’s wearing, bought from a garage sale, are in fact women’s pants. The response is classic Igor: “So? Am I supposed to care?”

Nothing need be new in Igor’s world, and nothing is to really be needed at all. “If the world collapses tomorrow, I need nothing,” he says. “I can just run my business for years without buying $1 worth of equipment.” Of course, the nature of all this “stuff” he boasts about, and its origins, are where his trouble stems from. On acquiring stolen property, Igor is quick to place himself in the midst of an elaborate system, a trapped cog in a perpetual wheel: “But everything is hot until it’s proven it’s not, right?” The old seedy Queen West that was Igor’s home turf enabled him to nurture these delusions and prosper; its gentrification both furnished his cache and hastened his downfall.—Tara Quinn