I come from a land of tragedy called Afghanistan.

My life has taken some unusual turns, but in many ways my story is the story of a generation. For the thirty years I have been alive, my country has suffered from the constant scourge of war. Most Afghans my age and younger have only known bloodshed, displacement, and occupation. When I was a baby in my mother’s arms, the Soviet Union invaded my country. When I was four years old, my family and I were forced to live as refugees in Iran and then Pakistan. Millions of Afghans were killed or exiled, like my family, during the battle-torn 1980s. When the Russians finally left and their puppet regime was overthrown, we faced a vicious civil war between fundamentalist warlords, followed by the rule of the depraved and medieval Taliban.

After the tragic day of September 11, 2001, many in Afghanistan thought that, with the ensuing overthrow of the Taliban, they might finally see some light, some justice and progress. But it was not to be. The Afghan people have been betrayed once again by those who are claiming to help them. More than seven years after the U.S. invasion, we are still faced with foreign occupation and a U.S.-backed government filled with warlords who are just like the Taliban. Instead of putting these ruthless murderers on trial for war crimes, the United States and its allies placed them in positions of power, where they continue to terrorize ordinary Afghans.

You may be shocked to hear this, because the truth about Afghanistan has been hidden behind a smoke screen of words and images carefully crafted by the United States and its NATO allies and repeated without question by the Western media. You may have been led to believe that once the Taliban was driven from power, justice returned to my country. Afghan women like me, voting and running for office, have been held up as proof that the U.S. military has brought democracy and women’s rights to Afghanistan. But it is all a lie, dust in the eyes of the world.

I am the youngest member of the Afghan Parliament, but I have been banished from my seat and threatened with death because I speak the truth about the warlords and criminals in the puppet government of Hamid Karzai. I have already survived at least five assassination attempts and uncounted plots against me. Because of this, I am forced to live like a fugitive within my own country. A trusted uncle heads my detail of bodyguards, and we move to different houses almost every night to stay a step ahead of my enemies.

To hide my identity, I must travel under the cover of the heavy cloth burqa, which to me is a symbol of women’s oppression, like a shroud for the living. Even during the dark days of the Taliban I could at least go outside under the burqa to teach girls in secret classes. But today I don’t feel safe under my burqa, even with armed guards to escort me. My visitors are searched for weapons, and even the flowers at my wedding had to be checked for bombs. I cannot tell you my family’s name, or the name of my husband, because it would place them in terrible danger. And for this reason, I have changed several other names in this book. I call myself Joya — an alias I adopted during the time of the Taliban when I worked as an underground activist. The name Joya has great significance in my country. Sarwar Joya was an Afghan writer, poet, and constitutionalist who struggled against injustice during the early twentieth century. He spent nearly twenty-four years of his life in jails and was finally killed because he would not compromise his democratic principles.

I know that because I refuse to compromise my opposition to the warlords and fundamentalists or soften my speeches denouncing them, I, too, may join Joya on the long list Afghans who have died for freedom. But you cannot compromise the truth. And I am not afraid of an early death if it would advance the cause of justice. Even the grave cannot silence my voice, because there are others who would carry on after me. The sad fact is that in Afghanistan, killing a woman is like killing a bird. The United States has tried to justify its occupation with rhetoric about “liberating” Afghan women, but we remain caged in our country, without access to justice and still ruled by women-hating criminals. Fundamentalists still preach that “a woman should be in her house or in the grave.” In most places it is still not safe for a woman to appear in public uncovered, or to walk on the street without a male relative. Girls are still sold into marriage. Rape goes unpunished every day.

For both men and women in Afghanistan, our lives are short and often wracked by violence, loss, and anguish. The life expectancy here is less than 45 years — an age that in the West is called “middle age.” We live in desperate poverty. A staggering 70 per cent of Afghans survive on less than two dollars per day. And it is estimated that more than half of Afghan men and 80 per cent of women are illiterate. In the past few years, hundreds of women have committed self-immolation — literally burned themselves to death — to escape their miseries.

This is the history I have lived through, and this is the tragic situation today that I am working with many others to change. I am no better than any of my suffering people. Fate and history have made me in some ways a “voice of the voiceless,” the many thousands and millions of Afghans who have endured decades of war and injustice.

For years, my supporters have urged me to write a book about my life. I have always resisted because I do not feel comfortable writing about myself. I feel that my story, on its own, is not important. But finally my friends persuaded me to go ahead with this book as a way to talk about the plight of the Afghan people from the perspective of a member of my country’s war generation. I agreed to use my personal experiences as a way to tell the political history of Afghanistan, focusing on the past three decades of oppressive misrule. The story of the dangerous campaign I ran to represent the poor people of my province, the physical and verbal attacks I endured as a member of Parliament, and the devious, illegal plot to banish me from my elected post — all of it illuminates the corruption and injustice that prevents Afghanistan from becoming a true democracy. In this way it is not just my story, but the story of my struggling people.

Many books were written about Afghanistan after the 9/11 tragedy, but only a few of them offer a complete and realistic picture of the country’s past. Most of them describe in depth the cruelties and injustices of the Taliban regime but usually ignore or try to hide one of the darkest periods of our history: the rule of the fundamentalist mujahideen between 1992 and 1996. I hope this book will draw attention to the atrocities committed by these warlords who now dominate the Karzai regime.

I also hope this book will correct the tremendous amount of misinformation being spread about Afghanistan. Afghans are sometimes represented in the media as a backward people, nothing more than terrorists, criminals, and henchmen. This false image is extremely dangerous for the future of both my country and the West. The truth is that Afghans are brave and freedom-loving people with a rich culture and a proud history. We are capable of defending our independence, governing ourselves, and determining our own future.

But Afghanistan has long been used as a deadly playground in the “Great Game” between superpowers, from the British Empire to the Soviet empire, and now the Americans and their allies. They have tried to rule Afghanistan by dividing it. They have given money and power to thugs and fundamentalists and warlords who have driven our people into terrible misery. We do not want to be misused and misrepresented to the world. We need security and a helping hand from friends around the world, but not this endless U.S.-led “war on terror,” which is in fact a war against the Afghan people. The Afghan people are not terrorists; we are the victims of terrorism. Today the soil of Afghanistan is full of land mines, bullets, and bombs — when what we really need is an invasion of hospitals, clinics, and schools for boys and girls. I was also reluctant to write this memoir because I’d always thought that books should first be written about the many democratic activists who have been martyred, the secret heroes and heroines of Afghanistan’s history. I feel the same way about some of the awards that I have received from international human rights groups in recent years. The ones who came before me are more deserving. It is an honor to be recognized, but I only wish that all the love and support I have been shown could be given to the orphans and widows of Afghanistan. For me, the awards and honors belong to all my people, and each distinction I receive only adds to my sense of responsibility to our common struggle. For this reason, all of my earnings from this book will go toward supporting urgently needed humanitarian projects in Afghanistan aimed at changing lives for the better.

As I write these words, the situation in Afghanistan is getting progressively worse. And not just for women, but for all Afghans. We are caught between two enemies — the Taliban on one side and the U.S./NATO forces and their warlord friends on the other. And the dark-minded forces in our country are gaining power with every allied air strike that kills civilians, with every corrupt government official who grows fat on bribes and thievery, and with every criminal who escapes justice.

During his election campaign, the new president of the United States, Barack Obama, spoke of sending tens of thousands more foreign troops to Afghanistan, but he did not speak out against the twin plagues of corruption and warlordism that are destroying my country. I know that Obama’s election has brought great hopes to peace-loving people in the United States. But for Afghans, Obama’s military buildup will only bring more suffering and death to innocent civilians, while it may not even weaken the Taliban and al-Qaeda. I hope that the lessons in this book will reach President Obama and his policy makers in Washington, and warn them that the people of Afghanistan reject their brutal occupation and their support of the warlords and drug lords.

In Afghanistan, democratic-minded people have been struggling for human and women’s rights for decades. Our history proves that these values cannot be imposed by foreign troops. As I never tire of telling my audiences, no nation can donate liberation to another nation. These values must be fought for and won by the people themselves. They can only grow and flourish when they are planted by the people in their own soil and watered by their own blood and tears.

In Afghanistan, we have a saying that is very dear to my heart: The truth is like the sun: when it comes up nobody can block it out or hide it. I hope that this book and my story will, in a small way, help that sun to keep shining and inspire you, wherever you might be reading this, to work for peace, justice, and democracy.

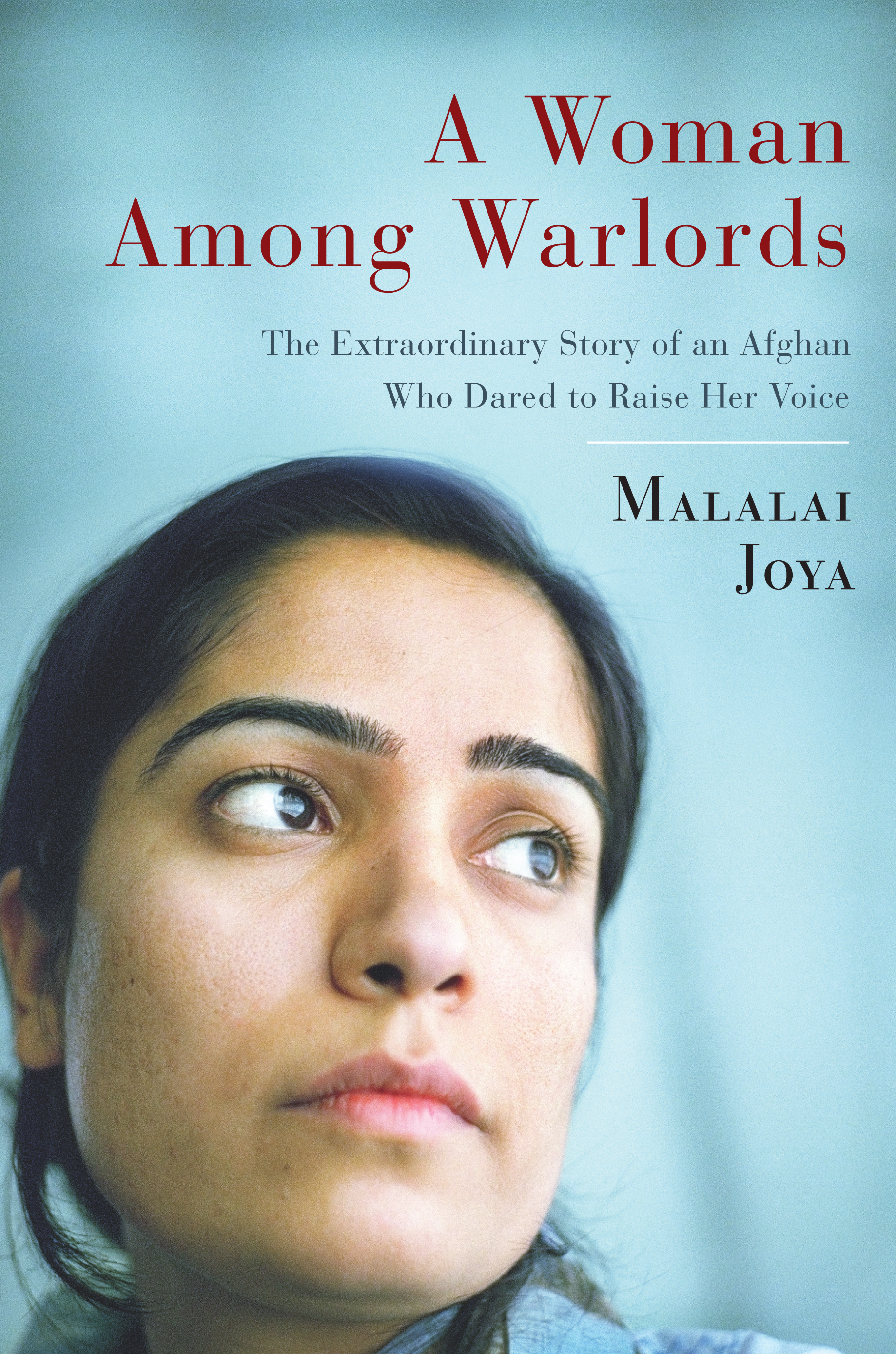

Excerpt from A Woman Among Warlords:The Extraordinary Story of an Afghan Who Dared to Raise Her Voice by Malalai Joya and Derrick O’Keefe published by Scribner 2009. Reprinted with permission.