An announcement of spring, dancing around a pole, crowning a queen, fertility rituals, assorted festivities — joyful community celebrations of the month of May can be traced back through the ages.

May Day or International Workers’ Day — another way of observing the first day of May throughout the world — is not quite as old, and has been more contentious. As political economist Leo Panitch argues, for the last one hundred years, “May Day has symbolized the common struggles of workers around the globe.” The day, with its own themes of renewal and change, represents a history of protest.

Canadians and U.S. citizens are familiar with the celebration of Labour Day on the first Monday in September as a labourers’ holiday, a day that usually marks the end of summer vacations and the beginning of a new school year. But the history of May Day is somewhat more obscure. As Panitch points out, the claiming of May 1 as a day for political protest grew out of the particular nature of working-class activism of Europe and North America in the late 19th century. During that time labourers were encountering ferocious industrial capitalists who sought to limit workers’ control over their jobs; working people in turn fought back by demanding shorter hours and better conditions. In May 1872, for example, Canadian workers joined the movement to fight for the nine-hour work day and, through strikes and demonstrations, pressured Canadian prime minister John A. Macdonald to pass the Trade Unions Act, making labour unions legal for the first time. Although the Act did not bring about the radical change that many workers had hoped for, the legislation signalled a victory, however limited, in what many of them were beginning to recognize as class warfare.

On 1 May 1886, in many North American cities, hundreds of thousands of workers mobilized for a one-day strike to demand the eight-hour working day. In Chicago tensions boiled over as the demonstration was transformed into a movement to support workers who, because of their union-organizing activities, had been targeted and locked out of a local factory. A few days later in Chicago’s Haymarket Square demonstrators gathered to hold a rally in sympathy for the workers and to protest police violence. When someone threw a bomb into police ranks, the officers reacted quickly, using the incident to justify a violent crackdown. A number of working-class activists and known anarchists were subsequently convicted and later hanged for the incident, although it was determined in court that none of the defendants had thrown the bomb.

A few years later, in 1889, the founding congress of the Second Labour and Socialist International declared May 1 as a day in which workers around the world would take to the streets to honour the lives of the Haymarket Martyrs, fight for better working conditions, and demonstrate solidarity amongst working people of the world.

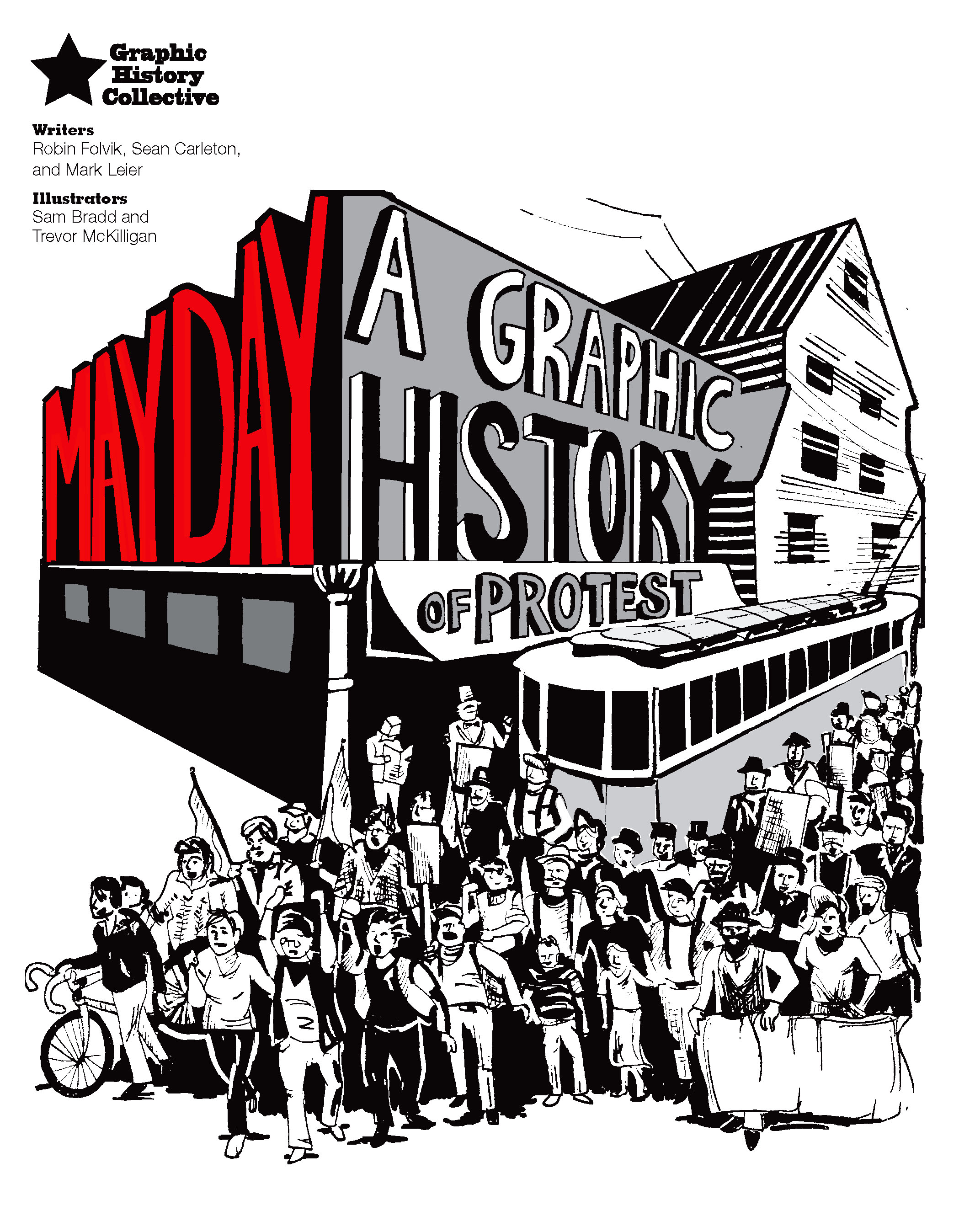

Now, using the creative and accessible medium of a comic book, May Day: A Graphic History of Protest, aims to bring these and other important stories of May Day to life, paying particular attention to the Canadian dimensions. In these pages, then, we seek to tell the rousing story of how, for over one hundred years, workers in Canada have used May Day to mark an important day for working-class celebration and activism.

To contribute to the deep and rich history of May Day, the Graphic History Collective offers this comic in hopes that you will be inspired to help reclaim May Day for yourself and your community and keep its fighting tradition alive. In addition, by completing this project we seek to add to the writings on Canadian labour history as well as to the growing field of political graphic novels. Since the publication of Will Eisner’s A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories (1978) and Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale (1986, 1991) there has been an increase in graphic works that combine radical politics with the medium of the comic book, as a mixture of sequential art and storytelling. More recently, writers and illustrators have offered a range of works, from Chester Brown’s Louis Riel: A Comic Strip Biography (2003) and Wobblies! A Graphic History of the Industrial Workers of the World (2005) to Sharon Rudahl’s A Dangerous Woman: The Graphic Biography of Emma Goldman (2007), Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of American Empire (2008), and Gord Hill’s The 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book (2010). All of these works make it clear that comics have much to offer activists in the twenty-first century. We hope that May Day: A Graphic History of Protest not only adds to this tradition but also, more significantly, underlines the importance of taking back May Day as an essential day of worker celebration and protest. We hope you enjoy our comic book!—The Graphic History Collective