Academic conferences don’t usually muster public attention, but in 2009 the organizers of the blandly titled Israel/Palestine: Mapping Models of Statehood and Paths to Peace found themselves at the center of a media shit storm fuelled by the hysterical rhetoric of pro-Israel community groups and their supporters in the media. This reaction culminated in an unprecedented move by Conservative Minister of State Gary Goodyear to threaten the funding of Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) — an arms-length agency created by an act of parliament — if it did not commit itself to a review of the funding it had already awarded by an independent peer-review process.

The conference, which took place June 22-24, 2009, was sponsored by York University, Queen’s University and SHHRC, and was held at York’s Glendon College. A range of international speakers and experts on the Israel-Palestine conflict, including many visiting scholars from Israel, took part. The aim of the conference, as stated in the SHHRC application and reaffirmed continually by the organizing committee, was “to juxtapose the two model for resolving the Israeli/Palestine conflict in a rigorous and thoughtful manner…The conference will open avenues to explore whether the a two-state solution or a single constitutional democracy in Israel/Palestine is the most promising path to future peace and security in the region.”

At the heart of the Mapping Models controversy was the conference’s conferring of academic legitimacy to the examination of “one-state” solutions to the Israel-Palestine conflict. Though one-state models were championed by a minority of early Zionists, including the philosopher Martin Buber and Hebrew University founder Judah Magnes, today any proposition that does not affirm a commitment to a “Jewish state” is considered dangerously radical and, in some Zionist quarters, even anti-semitic.

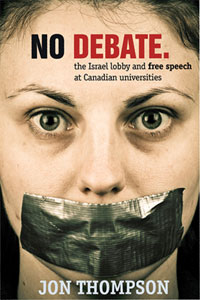

Though the three-day conference went ahead in June 2009 without incident, the organizers, concerned over what they saw as attempts to undermine their academic freedom by the government, the media, and their own colleagues and administration at York University, where two of the organizers taught and where the conference took place, sought assistance from the Canadian Association for University Teachers (CAUT). CAUT launched an investigation into the pre and post-conference handling of this event. Jon Thompson, who has written about the Nancy Olivieri case at University of Toronto about corporate interference in medical research, was assigned the task, and the result is a new book, No Debate: The Israel Lobby and Free Speech at Canadian Universities.

Institutionally, universities serve and always have served the interests of power, but they nevertheless contain spaces that are among the few places left in North America where informed discussion about Palestine can take place outside the well-funded apparatus of Israeli sponsored hasbara (propaganda).

No wonder then, as public impatience and disgust grows over Israel’s increasing belligerence, that pro-Israel groups and individuals have focused so much energy on attacking academics critical of Israel and pouring money into Zionist campus groups. Norman Finklestein, to take one high profile example, was denied tenure at DePaul University thanks to a smear campaign by Alan Dershowitz. At the moment there is a campaign against Mark Ellis, Director of the Center of Jewish Studies at Baylor University. Though Finklestein is a child of Holocaust survivors and Ellis is a rabbi, their criticism of Israel has made them targets — more so, perhaps, because their Jewish “credentials” make them particularly threatening.

Even Jenny Peto, a Jewish graduate student at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, was subject last year to a two-week smear campaign in Canada’s national media over a master’s thesis — a big term paper, really — that was critical of the March of the Living, an annual Jewish youth tour of holocaust sites in Poland. So the arrival of Thompson’s book is timely.

Academic freedom: Right or privilege?

It’s easy to slip into liberal indignation over attacks on academic freedom, but as Palestinian writer and activist Omar Barghouti has cautioned, it’s important to be clear that academic freedom is a privilege, not a right.

This is a distinction that matters in the context of calls to support the Palestinian struggle by boycotting Israeli academic institutions, a tactic that Israel’s defenders cite as a violation of academic freedom. As Barghouti points out, such defences of academic freedom establish themselves on a perverse hierarchy in which academic privileges take precedence over human rights. So, one must be careful when defending academic freedom not to proceed from the assumption that academic freedom is an absolute value.

As a privilege, academic freedom is not and never has been available to all. This is not to say that attacks on academic freedom should not be condemned and challenged — indeed they should — only it is important in defending academic freedom to not reinforce liberal myths of freedom and the academy that actually silence people.

In “No Academic Exercise: The Assault on Anti-Racist Feminism in the Age of Terror,” Sunera Thobani (ex-chair of the Status of Women) writes,

…like the liberal ideology it sustains, the construct of academic freedom is deeply political as it seeks to neutralize politics oppositional to liberal regimes. Defining individuals in the academy in the language of abstraction, removing us from the context of class, gender, race, and other social relations, it claims to be blind to these social relations. In this manner, academic freedom helps to reproduce these very relations of power.

Such issues are not raised by Thompson in his look at the attacks on the Mapping Models of Statehood conference. For the most part, No Debate is grounded in a liberal critique of threats to academic freedom and a liberal view of the university as a place of free inquiry that has come under attack.

Nevertheless, while Thompson doesn’t explore the ways in which universities have traditionally silenced or marginalized those from outside the hegemonic centre — by imposing, for example, parameters around the delivery of knowledge and the language it must be expressed in — he is very good in detailing the ways in which academic freedom has historically been circumscribed by the demands of governments, corporations, and private donors. “He who pays the piper calls the tune,” as the old expression goes, and Thompson is right on the money when he talks about the corrupting influence of “large funding resources from public or private funding sources for research work promoting or subservient to specific or commercial agendas.”

Thompson also provides a good historic overview of the legal and policy evolution of academic freedom in Canada, as well as (not surprisingly) CAUT’s important role in developing it. CAUT, he argues, can take credit for enshrining in faculty manuals and collective agreements all over the country a definition of academic freedom that explicitly includes the right to criticize the university, an achievement he ascribes to the reorganization of faculty associations during the post-war period into trade union-type bargaining agents.

The main purpose of No Debate, of course, is to investigate if and how these policy protections for academic freedom were violated before, during, and after the Mapping Models of Statehood conference, and in this Thompson proves a diligent researcher. Using access to information requests, he has waded through countless e-mails to provide a detailed account of who said what and when. Thompson commends the administration at Queen’s in Kingston, where organizing committee member Sharryn Aiken is a faculty member, for standing firm against outside pressures to censure her and distance itself from the conference. Similarly, President Mamdouh Shoukri of York University comes off rather well, particularly for doing an “end-run” around Associate Vice-President (Research) David Dewitt and Osgood Dean Patrick Monahan, both of whom Thompson admonishes for crossing the boundaries of professional conduct in exerting negative pressure on the conference organizers.

The Israel lobby

Thompson’s book also looks at what he calls the “Israel lobby,” which is a somewhat ill-defined collective term that encompasses a number of different groups, as well as individuals, some of whom can’t stand each other, acting independently yet with complementary purposes. Thompson, for example, notes humorously that despite concern the conference would provoke a situation on campus that would require an extensive security presence, there was, in the end, only one conflict, and that was between two Zionist groups, the Jewish Defence League (JDL) and the student campus group Hillel. It seems that the nominally liberal Hillel demonstrators did not want to be seen standing next to their more extremist JDL allies.

What emerges from Thompson’s summary of events is that when it comes to outside groups like B’nai Brith, the JDL, and the Canadian Israel Jewish Affairs Committee (CIJA), while they contributed to creating a climate of intimidation and put pressure on some members of the York University administration, particularly as the controversy threatened to alienate donors, their sphere of influence was and remains primarily outside (but above) the university, in the media and in the halls of government power.

The media campaign against the conference was driven largely by a single man, Gerald Steinberg, an Israeli academic and founder of the justly maligned NGO Monitor, which is often compared (not flatteringly) to Daniel Pipes’s notorious snitch site Campus Watch. Steinberg’s editorials were published widely by several major newspapers that never questioned his academic credibility.

Steinberg’s editorials were so rhetorically over the top — he said the conference would turn York University “into a macabre circus that sells hatred, martyrdom, and murder” — it’s amazing any newspaper saw fit to publish him. Similarly, B’nai Brith engaged in accusations that were so ludicrous — including accusations that some of the conference speakers were Holocaust deniers — they eventually had to issue a formal apology over threats of libel. The Jewish Defense League, mimicking the language of the Palestinian BDS movement, threatened to begin a campaign of “boycott, divestment, and sanctions” against York University, a threat that should have been readily dismissed not only because the JDL’s counterparts are banned in Israel and classified as a terrorist organization in the United States, but because its Canadian chapter consists primarily of a small group of extremist wing-nuts whose core membership numbers barely a few dozen people.

A motley crew of cranks and crackpots they may be, but this “Israel lobby” is consistently able to hit and pitch beyond its weight because its priorities are aligned with those of people in power. As Yves Engler writes in Canada and Israel, “The truth is pro-Israel Jewish lobbyists appear influential because they operate within a favourable political climate. They are pushing against an open door.”

Thus it was that the JDL, an extremist group with no wide base of support in mainstream Jewish circles, was suddenly jettisoned into national prominence in 2009 after its simple complaint to the Harper government resulted in the banning of British MP George Galloway from entering the country and giving a public talk. And thus it was again that a handful of news releases and a few sketchy editorials by a right-wing pro-Israel polemicist resulted in a government threat to slash funding to SSHRC if it did not fall in line behind the Harper agenda.

The limits of truth when state interests speak

The principal of academic freedom in modern times, as it was first articulated by the 1915 “Declaration of Principles” of the newly formed American Association of University Professors (AAUT), rested on the assumption that objective truths exist and that academics needed to be free from the demands of politics and university administrators to uncover them. A range of critical approaches since then, many associated with post-modernism, eventually exposed the partial, biased, and discriminatory nature of past truths. But no group has made more use of post-modernist challenges to truth as Zionists, for whom the term “Palestinian narrative” precludes the possibility that it contains any truth.

Indeed, one of the things revealed in Thompson’s book is how conventional notions of expertise get jettisoned when the topic of Israel-Palestine comes up. As Queen’s University Professor Adnan Husain commented during a conference panel on academic freedom I helped organize in 2009, when it comes to Israel-Palestine, the widespread perception is that there is no such thing as expertise but only entrenched positions.

One of the frequent accusations made against both the organizers and some of the participants of the Mapping Models of Statehood conference was that they lacked “expertise.” Thompson notes repeatedly, for example, that Dean Monahan, who by his own admission lacked expertise in the Israel-Palestine conflict, felt nevertheless capable of determining that the Organizing Committee lacked expertise, even though one of its members, Mazen Masri, was an Israeli-born Palestinian and former legal consultant to the PLO. For advice Monahan turned to York professor Irving Abella, whom he acknowledged in a separate e-mail was also not an expert.

Conference participants Ali Abunimah and Jeff Halper were dismissed frequently as “activists,” despite the fact that Halper is a retired academic and both he and Abunimah have between them a long list of scholarly articles on the Israel-Palestine conflict. The irony is that Halper’s and Abunimah’s extensive first-hand knowledge of the Israeli occupation in any other context would confer them with the credibility to speak authoritatively. Yet in the context of Israel-Palestine, first-hand experience — what in Halper’s field of anthropology they call field work — actually diminishes their ability to speak as “experts.”

Where there is no belief in truth, the default position is to demand “balance,” which organizers of Mapping Models bent over backwards to accommodate, despite the fact that, as Thompson notes,

There is no general requirement in Canadian universities that the membership of a research team be balanced or that a research project be balanced in a political or ideological sense, nor is there such requirement in SSHRC regulations.

Moreover, as the organizers’ efforts to “balance” the content of the conference were being deemed insufficient, a conference at the University of Toronto’s Munk Center took place in March 2009 called “Emerging Trends in Anti-Semitism and Campus Discourse,” which contained a decidedly one-sided speaker’s list that no one demanded be “balanced.”

Universities have never been the bastions of academic freedom that some have liked to think they were, but I do agree with Thompson’s conclusion that current trends suggest the “existing frameworks that protect the public interest will continue to be eroded” both by the global entrenching of neo-liberal economic policies and by the aggressive acceleration of those policies under our current, highly ideological government. The worst, I fear, is still to come.—Jason Kunin

Jason Kunin is a Toronto teacher and writer. This review first appeared in Socialist Sollidarity.

Dear rabble.ca reader… Can you support rabble.ca by matching your mainstream media costs? Will you donate a month’s charges for newspaper subscription, cable, satellite, mobile or Internet costs to our independent media site?