Street Stories: 100 Years of Homelessness in Vancouver by Michael Barnholden and Nancy Newman with photographs by Lindsay Mearns (Anvil Press, 2007; $20.00)

At first glance, Street Stories: 100 Years of Homelessness in Vancouver and Hope in Shadows: Stories and Photographs of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside appear to tackle the same subject – exploring the lives of the city’s poor and homeless. However, upon closer examination these two very different projects show us that the Downtown Eastside is about far more than homelessness and that homelessness is not limited to the Downtown Eastside. Through engaging photographs and stories both books attempt to articulate the larger context of social and political factors contributing to poverty and homelessness in the city of Vancouver.

They achieve these ends with varying degrees of success.

Street Stories opens with an essay which traces the social attitudes, events and legislation that have contributed to homelessness throughout the past century. The second half of the book attempts to provide a more intimate look at contemporary circumstances of homelessness through photographs and brief interviews. The combined intent of these sections seems to be to encourage a re-visioning of the way most of us regard homelessness.

As Barnholden and Newman explain in their essay, the language and imagery historically used to discuss homelessness and to describe the homeless betrays a persistent social stigma characterizing this population as dirty, hopeless, lazy and fundamentally responsible for their own sorry fate. Instead, they suggest,

"when we speak or write about the problem of homelessness, we are talking about individual tragedies. The dignity of the individual is paramount, and we must respect that dignity by telling a story that is as full and complete as possible, by placing individuals within a context that reveals as much about other members of society as it does about them."

In as much as the book succeeds at doing this in the essay section – where links are clearly drawn between individual lives, wider social attitudes, legislation and a diminishing public safety net – it fails to do so in the photographic portion of the book. Relatively little contextual information is provided through the photographs, where subjects are often depicted alone, in tightly framed shots. Only slightly more information is supplied by the brief biographies that accompany each photograph. The brevity of each entry contributes to an overall impression that one is reviewing a catalogue of characters. With very little information to ponder, one tends to flip through the pages quite quickly without spending a great deal of time considering the lives of these individuals or the larger societal implications of their circumstances.

The voice in these passages is slightly confused in that the author/interviewer appears to be paraphrasing responses to a series of set questions without disclosing any of these questions to the reader. Although at times it seems like there may have been a uniform line of questioning pursued, the kind of information provided about each person is fairly inconsistent: in some cases age is disclosed and in others it is not, sometimes an individual’s reasons for being on the street are discussed and at other times not. Because there is little apparent consistency among the bios, the reader is left wondering how Mearns made decisions about what kinds of information to include. And insofar as our impressions about these individuals are so much informed by the construction of these brief passages, it seems irresponsible of the author not to address her own role in shaping these biographies.

There is relatively little discussion in the book about Mearns’ process and motivation for undertaking this project. What we do know we learn from one brief page which explains how Mearns made a commitment to raise awareness about marginalized individuals in her community while taking a Landmark Education self-development seminar. Her process was to then enlist a crew of friends and family to assist her in photographing and "capturing the stories of the people they met face-to-face as they walked the streets…."

There is little else explained about the process of assembling these stories and the reader is left with many questions, such as: Why were these particular subjects approached for interviews? What were they told about the project? Were they offered the opportunity to review their photographs and biographies before publication? Were they offered any compensation for their participation? Did those taking the photographs and conducting the interviews have any specific ties to any of the subjects? Were they all approaching their subjects in a similar way? And why was the only topic consistently addressed in most of the stories "advice to young people thinking of a life on the streets"? By neglecting to address so many of these questions, Mearns omits the important discussion of the story behind these "stories." There is much more to these subjects’ lives than we are immediately shown on these pages and the process of capturing these photographs and biographies is equally important to explore if we are to truly engage in a more inclusive discussion of homelessness.

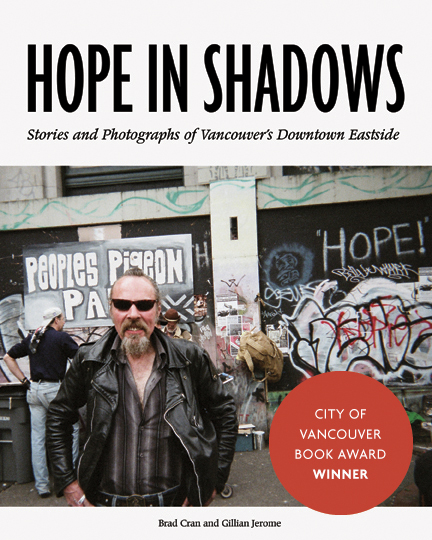

Hope in Shadows takes great care to explain the process by which its subjects’ stories and photographs have been assembled. The result is a more coherent sense of the project’s scope and intent. Arguably, it has a more focused political purpose than Street Stories: to advocate for greater societal appreciation of the Downtown Eastside (DTES) as a valuable and vibrant community, and to promote the work of the Pivot Legal Society specifically.

The book’s opening preface, the essay on the work of Pivot and the informative foreword by Libby Davies all provide meaningful historical and contextual background for the stories and images about the DTES. They explain how this book developed out of a community-empowerment project run through a local grassroots advocacy group. And how the original act of sending people out with cameras to document their own community became a successful launching pad for a treasury of images to appear in galleries, calendars and this book.

In the preface, the authors also diligently explain the approaches they used to document individuals’ stories. All participants were informed as to the project’s purpose before choosing whether or not to take part. The writing process itself involved lengthy interviews and close collaboration between writers and subjects so that detailed first-person narratives could be developed. And all participants were given an opportunity to review final drafts before they went to publication. In contrast to the very loose methodology employed by Mearns and her recruits who casually "set out with cameras, notebooks, and packages of cigarettes" to capture the stories of their fellow city-dwellers, the methods employed by Cran and Jerome’s team appear exceptionally careful and considered.

The Hope in Shadows project is very successful in evoking lasting impressions of its featured participants. The photographic and written components work well in concert to create a strong sense of each individual’s life circumstances, attitudes, aspirations and fears. In part, this is because the narrative passages are satisfyingly well-developed and conversational in tone, enabling each participant’s individual voice to shine through. But, it is also attributable to having the camera lens directed by the individual rather than trained on the individual. Each of these photographs – which are remarkably complex and reflective of many different aspects of day-to-day living in the DTES – provides a great deal more information about how these individuals view the world and relate to their community than a basic portrait would.

These images and stories provide opportunities for real insight into what people in this community are interested in, what they value, where they come from and what they continue to struggle with. Insofar as this project intends to encourage greater compassion for the DTES by "creating a safe vantage point for people to care about and understand" this community, I think it succeeds.

Where Street Stories falls short of its mission by presenting a series of documentary snapshots which fail to create a strong sense of the individual, Hope in Shadows provides a more complete record of individual lives – one that succeeds in "placing individuals within a context that reveals as much about other members of society as it does about them." In so doing, it promotes the dignity of the individual and fosters greater respect, understanding and compassion for this community.–Philippa Mennell

Philippa Mennell is a designer and freelance writer based out of Vancouver, who is currently enjoying the wonders of farm life in Sooke, B.C.