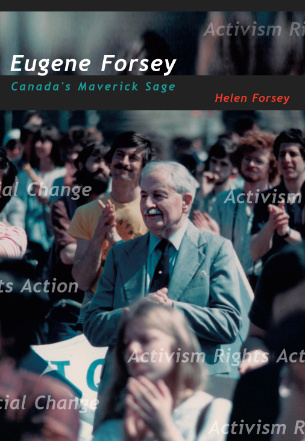

In this excerpt from her book, writer and activist Helen Forsey remembers her father, senator, constitutional expert and rabble rouser, Eugene.

One of my favourite pictures of my father appeared in the Ottawa Citizen on a September day in 1974. It showed him picketing in front of the Chilean Embassy on the first anniversary of the bloody military coup that overthrew that country’s democratically elected socialist government and launched the brutal Pinochet regime. He was carrying a sign that read: “RESTORE CIVIL LIBERTIES IN CHILE.”

A year earlier, the day after the coup itself, he had risen in the Senate to declare: “This was a tragedy, not only for Chile and for South America, but for the world. Here was a case where there seemed to be some hope that revolutionary developments — which I think were highly necessary in that country — would be carried through by democratic and constitutional means. It now appears that this hope has been destroyed, and I cannot help feeling that this will provide sad ammunition for subversive elements throughout the world, who will be in a position to say… ‘Learn the lesson. The thing is hopeless. It cannot be done except by violence.’ To my mind this is a great tragedy.”

That picture, and the excerpt from the Senate Hansard, sum up for me a great deal of what my father was about. It’s all there: his enduring commitment both to “revolutionary developments” and to peaceful, constitutional means for achieving them; his concern for civil liberties, here and elsewhere in the world; his own unassuming personal participation in grass-roots protest.

In Dad’s later years, public coverage of his ideas and activities focussed mainly on the constitutional and national unity aspects of his work. As a result, it was not always obvious how broad and progressive his perspective was. Yet that perspective was never absent. As the world changed and new challenges emerged, he continued to dedicate his energies to the common good.

Dad had always been an internationalist by inclination. His travels as a young man in Europe and the Soviet Union, his facility with different languages, his study of constitutional issues in Commonwealth countries, and his international connections with other democratic socialists and labour people had all broadened his horizons far beyond Canada’s borders.

His trip to India in 1953 for the World University Service Seminar, and the friendships that resulted from it, strengthened his international perspective and deepened his awareness of the so-called “developing” world. On his return, he reflected on what had been, for him, a hugely significant experience: “Across half the world, across differences of creed and colour and political belief, we built bridges which I think will last.” And last they did.

“Senator Rails Canadians to Help Third World” ran the headline on an Ottawa Citizen article in November, 1976. “The wealth of Canadians is scandalous in contrast to the horrifying poverty of most the world’s people, Senator Eugene Forsey said Sunday. In a vigorous speech, the 72-year-old senator told Carleton University’s 64th convocation that egotism and indifference must end if Canada is to respond properly to the needs of the Third World…”

That speech reflected the very serious apprehensions he felt about the scope and urgency of planetary problems. His message to the graduates was not a soothing one. In it he challenged them to address the “new and inescapable realities” facing Canadians and the world-the growing scarcity of energy, raw materials, and food; the growing power and rising expectations of the people producing those things; the exponential growth of world population; and, last but not least, the massive threat of pollution.

Still, his speech was neither a guilt trip nor a dirge of despair; it was a call to action. The future, he said, would demand: “much plainer living, much harder thinking, much more intense feeling for the disadvantaged and the disinherited, in our own country and across the world. We, the non-poor, are going to have to adjust ourselves to a new scale of priorities… to accept a considerable, even a massive, redistribution of wealth and resources.”

That adjustment would mean we would have to change not only our economic expectations but also much of our dependence on modern conveniences and technology. Dad emphasized that this would be far from easy.

“Getting large masses of people to change their minds on those subjects which directly, and deeply, affect their own incomes and their own convenience is a huge and daunting job,” he said. “The changes that will have to be made will run into fierce, and understandable, resistance… ‘What! Clear the private automobile out of the city centres, stop poisoning the atmosphere and stop gargantuan waste of an irreplaceable source of energy?'”

Then, risking the wrath of purists on the left, he ventured further. “That resistance will come not only from the rich, the tycoons, the multi-national corporations, but also from the unions in the prosperous industries which flourish on squandering resources, on polluting air and water and devastating countrysides… The welkin will ring with the outraged cries of big business and little, of unions and their members, of municipal, provincial and national electors.”

His blunt realism was also constructive. He stressed the need for the kind of approach the labour movement has called “a just transition” for affected sectors and communities. “Devising the means to cushion the blows,” he said, “to provide alternative employment and income for people displaced by the changes, will tax the ingenuity of statesmen and economists. Persuading the democratic electorate to accept the changes, even with workable plans to look after the displaced, will tax the resources of educators, elected politicians, and elected labour leaders.

“Government and labour politicians can get only so far ahead of those whose support they must seek. They need all the help their constituents — which means us — can give them. Democracy, in its true sense, means not simply a system of government. It means us.”

Writer and activist Helen Forsey is the daughter of the late Senator and constitutional expert Eugene Forsey. Her book on her father’s legacy to Canadians, entitled Eugene Forsey: Canada’s Maverick Sage, is being published this April by Blue Butterfly Books. This excerpt is reprinted with permission.