I usually get very excited about reading a book written by a residential school survivor and this instance was no exception. I experience joy in that we are now hearing survivors’ voices that had in the past been silenced.

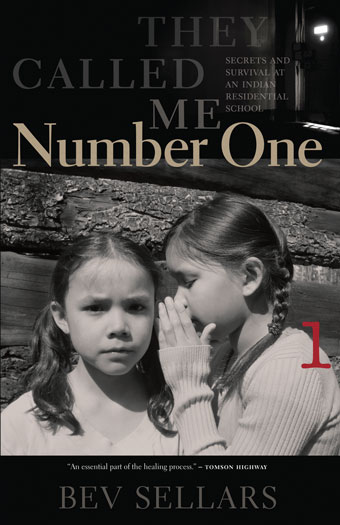

Bev Sellars’ They Called Me Number One: Secrets and Survival at an Indian Residential School details Sellars’ life from the time she was five years old until the age of 58 and she notes four reasons she felt compelled to write this book.

First, Sellars wanted to recognize that in the early 1990s “our communities first began to explore and deal with the aftermath of the Indian residential schools.”

Second, Sellars wanted to share her experience with fellow survivors — those she knew who were suffering the same experiences.

Third, through the process of writing, Sellars felt she was “still disassembling the restrictive world in which” she used to live and wanted to move forward in that process.

Lastly, Sellars was and continues to feel angry about the way Aboriginal people were treated and are still being treated in Canada and wanted to express and resolve some of that anger.

They Called Me Number One retraces Sellars’ life from a traumatic childhood through to her transition as a community leader and showcases her passion and her drive for education in succeeding in acquiring a law degree. As Sellars ages she reflects and realizes the impacts that residential school has had on her life.

The use of a non-chronological order and the movement back and forth potentially mimics Sellars’ understanding of how her life unfolded. You must be patient for reflection because it is more important than time.

“I felt an extreme sadness in the soul:” Experiences in residential school

Raised by her Gram, Sellars at age five contracted tuberculosis and was admitted to the Coqualeetza Hospital at Sardis outside Vancouver, British Columbia. She remained there for 20 months.

While at the hospital, Sellars grew to love a young blonde nurse who eventually left her employ when she got married. In spite of the closeness, the nurse neglected to say goodbye; however, it was because of this relationship, Sellars initially wanted to become a nurse.

When Sellars returned home, she tried to reconnect with her family, but three weeks later, at age seven, she was sent to St. Joseph’s Mission residential school, which was located on the Williams Lake First Nation lands in British Columbia. Sellars attended St. Joseph’s from September 1962 to June 1967.

A bed wetter, Sellars was punished and traumatized by the strap. She was “well acquainted with the feeling of loneliness,” but “learned to suppress it while in hospital.”

Through these experiences, Sellars reinforces the readers’ understanding of residential schools in that it was a “breeding ground for dysfunction” and that she was “so conditioned by a place” that “they really did control us by fear.”

Sellars says, “I learned that speaking my mind or questioning anything would only get me into trouble. Using my mind was even more unacceptable.” She has no memory of grade four.

As a teenager, Sellars came to understand two important life facets: (1) she “shouldn’t expect to be treated as an inferior by all white People” after becoming friends with three white girls, and (2) her life force energy was sparked when she was acknowledged by the traditinal dancerin full regalia, which spurred on her drive for education.

By age 18, Sellars was married and soon gave birth to two children. Later she adopted one additional child, but by then her marriage had dissolved and she had sought a restraining order against her abusive ex-husband.

Sellars attempted suicide — the first of many — and while in the hospital after getting her stomach pumped, a white nurse scolded her “You people!” The nurse made her feel so uncomfortable and “stupid” that as soon as the tubes were removed from her arms, Sellars left the hospital without her shoes.

She went to her Gram’s home for support and comfort as she sadly stated, “I felt an extreme sadness in the soul.”

Decolonizing the mind and becoming a success story

Sellars is incredibly insightful about her residential school experiences and the process of “decolonizing.” She references the amazing abilities of First Nations’ leaders Bill Wilson and George Watts in that they “were not prisoners in their mind like too many of us who attended the schools.” They were able to engage others from a position of strength and confidence.

As a survivor of residential school, Sellars felt that she lacked this ability. However, she is a success story despite the tragedies that befell her family and herself — a survivor in every sense of the word.

She achieved her lifetime goal by attending university, becoming a lawyer and writing a memoir. She is a testament that survivors can leave a positive legacy, despite the horrors experienced, and her story is a positive contribution to the growing literature on Canadian Indian residential schools.

As a reader, I noticed that only two chapters were devoted to her actual residential school experiences, and I acknowledge that writing and reflecting on those times are painful and that this book is only a snapshot of Sellars’ life.

There appears to be so much more that she can offer and that we can learn from her. There is no mention of her experiences attending law school and working for the Treaty Commission. Sellars’ insights detail her experience and the intergenerational residential school experiences of her grandmother and mother.

Sellars does not sugar coat the truth and did not make excuses for what happened. Her book is a reflection of her life and her understanding and of making sense of what occurred.

When she speaks about her brother, who committed suicide, she speculates that he did this because the principal of the residential school sexually abused him. The priest, now a Bishop, went on to be convicted in a court of law.

In the past I have worked with and listened to survivor voices and it is important to give voice to those survivors.

After reading Sellars’ work I felt some of my own reflections being stirred when she says she “cringed and the shame I felt at being Indian went deeper and deeper” and that “everything in society told me that I was not good enough because I was an Indian.”

I learned that we had to be better, to perform at a higher standard and change peoples’ minds about Indigenous women. In my experience with residential school survivors, humour was and has been instrumental in enduring horrid experiences. I agree when she states that, “I guess a sense of humour that Native people have is just another way of survival for us.”

Moving from surviving to thriving

So how did the author do? Did she succeed in fulfilling the reasons why she wrote the book?

Let us revisit the reasons.

Did she explore the aftermath of residential schools? Yes. I believe that she absolutely did.

Did she share with fellow survivors who were suffering? Yes. Her nephew, Robert Sellars, after reading Sellars’ draft, stated that he could now forgive his father as he understood what the survivors endured during their lifetimes and now understood why he had done certain things.

Did she disassemble the restrictive world she lived in? Yes. By taking control of her life, becoming an independent woman, being a community leader and attaining a law degree, she broke that “victim mould” which many residential school survivors are labelled.

Did she decrease her anger about the way Aboriginal people have been treated and continue to be treated? Yes. Sellars has given the readers an insight that we needed to hear.

“It is time we started living again and not just surviving.”

I have heard this from other survivors that they are thriving, not just surviving, and taking back what was taken away. The difference is that they are now the ones in control and they are doing it their way, which Sellars has also done.

Dr. Theresa Turmel is an Anishinaabe-kwe from Michpicoten First Nation. She completed the program requirements of the Ph.D. Program; Indigenous Studies from Trent University, July 2, 2013. Her dissertation titled, Gaagnig Pane Chiyaayong: Forever We Will Remain: Reflections and Memories: ‘Resiliency’ Concerning the Walpole Island Residential School Survivors Group, is the hallmark of significant learnings of a twenty plus year relationship she has fostered with the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association (CSAA) and its offspring, the Walpole Island Residential School Survivor Group (WIRSSG). Her dissertation is a participatory, community-based partnership with the WIRSSG whereby she discovers life force energy or mnidoo bemaasing bemaadiziwin and offers an Anishinaabe perspective of resiliency.

In her personal life, Theresa is the proud mother of three adult children, John, Danielle and Chantal and extremely proud grandmother of Ariel, Alexandra, Dylahn and Emma-Leigh and has been married to husband, Mike for the past thirty years. She achieved her BA from Laurentian University in 1992 and her Master in Public Administration in 1998 from Lake Superior State University. Theresa possesses a love of learning and she is guided by the traditional Anishinaabe teachings and traditionalists and never wants to stop her life long learning process of culture and identity.

Dr. Turmel’s interests include Traditional Teachings and Medicines, Cultural Revitalization and Health/Healing, Relationships, Social Justice issues, Ecology, Indigenous Literature, Criminology and Corrections and Indigenous Fashion and Design.