Official bicentennial celebrations of the “affable drunk” who founded Canada will likely mask John A. Macdonald’s history of racism and deliberate starvation of First Nations, and similar policies continue today with the tar sands and fracking expansion.

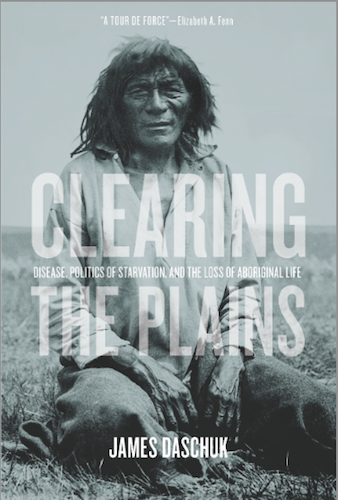

James Daschuk, author of Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life, addresses Canada’s history of disease, deliberate starvation, ethnic cleansing, tar sands expansion, neglect of treaties and a legacy of colonialism that continues today.

The resilience of Indigenous communities in the face of ongoing corporate and state coercion is incredible, and the problems of our age will not be resolved until Canada honours its relationship with First Nations. The prospects for change do not look good, and we have a responsibility to alter this perilous trajectory.

The politics of Indigenous starvation

Matthew: Your book is causing a nice stir and provoking lots of discussion about the history of Canada and First Nations relations. James, if we could open with what purpose your book serves in addressing the reality of First Nations today. It’s a historical picture, but I’d really like to pull it into the present.

I’ve given plenty of talks on this over the past few months since the book was launched. My point with the book was to try and identify the root of the current disparity in health and wellbeing between First Nations people in western Canada and the mainstream population.

Sean Atleo, who is chief of the Assembly of First Nations, wrote an open letter during the federal election campaign in 2011 and he said that young Aboriginal people have a greater chance of ending up in jail than finishing high school; that 114 Aboriginal communities across Canada had boil water orders; that tuberculosis was 30 or 34 times more prevalent in Aboriginal communities than the mainstream population.

So it’s really trying to identify how our First Nations neighbours can live in almost entirely different circumstances than we do, even though they’re physically not separated from us at all.

And you really trace a lot of those figures and statistics back to racism, and you point this out very clearly in the book, but also federal policies that deliberately deprived Indigenous people of food and forced them off their lands and onto reserves. Basically saying that the current situation with many First Nations communities is rooted in deliberate policies of starvation and racism.

Yes, so the United Nations Human Development Index usually has the mainstream population of Canada as among the top ten countries in the world, but if you use those same criteria for First Nations people, they are something like 68th or 70th [alongside Panama, Malaysia or Belarus].

Another thing I was shocked at was that these weren’t organic situations like the inadvertent introduction of diseases like smallpox. These were actually planned policies to get Aboriginal people off the land, and they were managed by John A. Macdonald in his role as minister of Indian affairs.

So for the first five years after his return to power in 1878, Macdonald was not only Prime Minister, he was also minister of Indian affairs. And he personally oversaw basically the directed famine and forced removal of Indigenous people from the territory of south-western Saskatchewan, forcing them onto reserves, where their health has never truly improved in comparison to the white population in the last 120 years.

From railways to pipelines

Right, and the logic behind that forced removal from the land — driven by John A. McDonald and his Conservative government — you very much say that it was an economic motive, forcing First Nations off the lands in order to make way for the railway. Can you maybe elaborate on that, and I am also interested in if any parallels can be drawn with the Harper Conservative government today and their resource-based projects.

Here’s another national economic action plan that directly affects First Nations communities. It’s this national vision of being an energy superpower very much in line with the railway and wanting to build a national project. So are there comparisons and similarities?

Sure, so in March of 1882, Macdonald said that the Indigenous people south of the proposed railway tracks in the territory of Assiniboine or south-western Saskatchewan would be removed by force if necessary. He made this statement in the House of Commons.

What they wanted to do was eliminate any threat to the construction of the railway — any impediment — and they wanted the land cleared for European settlers. So when the Europeans showed up over the next couple of decades, the land was literally cleared of people.

In the early spring of 1883, some 5,000 people had food withheld from them in the Cyprus Hills and were forced to march several hundred kilometers north to their reserves around Battleford, Saskatchewan. It was brutal but it was very effective. Only a few hundred people were still on the land and hadn’t taken up the reserves.

Parallels with the present? Yes, we have the second largest proven oil reserves in the world in northern Saskatchewan, and Mr. Harper and the oil companies are doing their best to get that oil extracted and to profit from it.

There’s an American scholar who’s talked about something called “sacrifice zones,” and I think that might apply to both of these situations. The national policy back in the 1880s was the central tenent of the Conservative government in their return to power in 1878.

Building the railway was the primary directive. They had to get built, and they had to get it built as quickly as possible. The health and wellbeing of 20,000 Aboriginal people was probably the cost to them for the successful completion of the railroad. They didn’t fit the paradigm, and they were dispensable from a 19th century perspective.

And if you bring that up 130-odd years, the few thousand Dene and Cree people in northern Alberta are in their protest with Neil Young and so on — they are seen as an impediment to development.

I think in the big picture, the government is putting the wealth of Canada — the gross national product — at the expense of Indigenous wellbeing. That’s the cost of doing business.

Honouring the Treaties?

You actually just mentioned Neil Young, the famous rock and folk singer. He recently took a strong stand and embarked on an “Honour the Treaties” tour. I am interested in your thoughts on that because, in your book, you make a fairly clear case that many of the treaties were used as tools by the Canadian state to force often starving and strained Indigenous groups into compliance. Could you speak about that, and the importance of treaties today?

Sure. With regards to the treaties — and I specifically mention Treaty 6 — it was signed in Fort Carleton in the summer of 1876. That was a truly hard-bargained treaty. The commissioner and the representative of the plains Cree negotiated in good faith, nation-to-nation, and they bargained hard for three days — I think it was August of 1876.

Within about a year-and-a-half or two years, when the buffalo disappeared and the plains Cree lost their position of military power, the federal government took advantage at every turn they could to basically subjugate and almost imprison people onto reserves using food as a weapon — as a form of coercion — and withholding food to anyone who didn’t submit to the will of the Indian department. So we do not have a very long history of good treaty relations in western Canada, for sure.

What would I tell anyone now, these days? Many of us in mainstream society think the treaties only involve some type of benefit to First Nations people, be it the misguided idea that First Nations people get free schooling or some type of special privileges.

I guess the way most of us in mainstream Canada should think about it is that the treaties are the legal basis upon which we have built one of the most affluent societies in the world, Canada, at the expense of the health and wellbeing of the original owners of the land.

The treaties are a legal recognition that Aboriginal people, First Nations people, were the owners of the land. Our ancestors and the institutions that came before us in the dominion of Canada could not have moved into the prairies without legally binding treaties. For 130 years, our federal institutions have not acted in accord with the spirit of those treaties.

Colonialism and the British Empire

Michael Welch: Because those treaties were signed with the crown of England, I was curious about whether the approach of the Canadian government of clearing the land for the railway, if there was a different attitude on the part of England.

Oh man. Well, we were a dominion, so we weren’t a truly sovereign country, but think about the role of England at this time in its colonial program across the world in relationship with railways.

At about the same time as the Canadian Pacific Railway was being built, there was a huge famine in India. So the English colonial powers that were managing India were using railways to export food from India to England at the same time that 400,000 people died of starvation in India.

So the Canadian aspect was part of a global colonial agenda that privileged setters and agrarian capitalism at the expense of whichever Indigenous people — be it Africa, be it India, be it western Canada.

I don’t know if people would have been shocked about Canada because there were probably worse things going on being reported in the papers in England.

Indigenous resistance today

Matthew: Interesting stuff, and also extremely depressing stuff. The book is relentlessly factual, and that is relentlessly depressing. You tell a story of war, violence, rape, alcoholism, racism, manipulation by colonial authorities, imposed starvation. You are almost hoping to get a breath of fresh air, and it feels as if it doesn’t come.

But reading the book, what I drew inspiration from were moments of resistance. Certainly, there were First Nations communities that took very strong stands. I’m thinking of that great quote when the police were trying to bribe Indigenous communities with gifts in order to introduce telegraph lines in the 1870s, and Chief Big Bear said “we want none of the Queen’s presents…let your chiefs come like men and talk to us.”

I couldn’t help but draw comparisons with some of the resistance that we see today, often led by women. The Mi’kmaq in Elsipogtog, many of the actions that we’re seeing around Canada and First Nations territories, and it does give a sense of hope. If you could speak to some of the resistance and some of those more uplifting moments.

The fact that Indigenous people have survived the 130-year onslaught of their language, residential schools, breaking family ties, attacks on religion, language, culture, you name it. The fact that First Nations still continue to exist and identify themselves as First Nations people — and demand their rights that were negotiated in treaties — is a testament to their strength. […]

Confronting the myth of a gentle Canada

Just two more quick questions. Like you’ve said, most Canadians don’t know this history. I’d like to know your thoughts on why that’s the case. Is it our education system, or political system? What is preventing young people from receiving this knowledge? You really have to dig deep to learn this stuff, and why is that?

Canadians are very judgmental when it comes to Americans and how they view themselves as the greatest and most powerful nation on earth, but every country probably burdens themselves with some myth that may or may not represent reality.

I think Canadians have this idea that we are fundamentally a decent and nice people, boring though we may be. These days, we’re in the middle of the Sochi winter Olympics, so we’re feeling good about ourselves.

But most of us in mainstream Canada really don’t recognise the terrible things that have been perpetrated on our behalf. The subjugation, the imposed hunger on First Nations, medical experimentation on children at residential schools […]

How would you address that? Obviously publishing books like yours, but how do we get that message across to particularly young people, but also people who don’t get to go to school?

I’m pretty hopeful for young people who are still in school these days. There was a travelling exhibit at the University of Regina in the fall, called A Hundred Years of Loss on the impact of residential schooling.

I taught an Indigenous studies class in French, and my students brought 180 K to grade 8 students through that exhibit in French, so several hundred students came through and got to experience that exhibit.

The residential schools are being integrated into the curriculum. I was lucky enough to be invited to the Saskatchewan School Boards Association, and spoke to several hundred school officials on the issues addressed in my book, and they are very interested in getting that information into the K-to-12 curriculum.

I think young people are going to be a lot more open than, sadly, the adult population. Things will change. It might be a generational thing, but just the fact that we’re speaking about this in the media is a good thing. I have a friend who has a quote on his email that says, “Once you learn something, you can’t unlearn it,” so just hearing these stories will change a lot of attitudes.

Revisiting the legacy of John A. Macdonald

I’m interested in some of the critiques that have been raised. Can you speak to some of the responses that you’ve had to your book.

I’m just staring at Richard Gwyn’s The Man Who Made Us, John A. Macdonald’s biography. There are a few biographers of John A. McDonald’s who feel that I’ve not told the full story of Macdonald’s relationship with First Nations people.

I’m not a biographer, and I didn’t really intend to be one, but we’re coming up to the bicentennial of McDonald’s birth and there’s going to be a lot of celebration of McDonald as the affable drunk who built Canada.

Everyone’s got a soft spot for him, but I teach a lot of First Nations students and he is almost universally despised by Indigenous people for his treatment of First Nations, so that will be an interesting thing.

So you may have seen something about the proposal to rename Union station in Toronto. One of Rob Ford’s antagonists, councillor Denzil Wong, proposed about a month ago to rename the station John A. McDonald station.

There’s been a pretty big debate. Bernie Farber from the Canadian Jewish Congress wrote a letter, and there are a few Chinese community activists talking about McDonald’s racism, basically toward their ethnic groups as well. It’s going to be interesting to see how the celebration of McDonald’s bicentennial will be met with a whole bunch of different people, including Indigenous people, talking about his negative role.

He did build Canada — there’s no doubt about that — with the railway and all that other stuff. But he also built the Canada of Oka, of New Brunswick, of unsettled land claims all over the place. So he built a country, but he built the screwed up country we live in today.

I want to close with one last question, because your book is theoretically very rich. You present the theory in a muted and accessible way that I really appreciate, but it’s actually very rich.

Capitalist Ecology Today

What you’re basically saying, drawing from world systems-type theory, is that when an economic system is being introduced, this also entails introducing an ecological system — so capitalist economies being introduced to a land also introduce capitalist ecologies.

So tying an economic system to the land, to our health, to our way of life and being — connecting all of these things in a very subtle way that I appreciate — could you maybe speak to that? This is a big question, but looking at that same model today with the tar sands and pipelines.

The agrarian settlement paradigm has functioned pretty well for the past 120 years. The plains Bison hunting tradition that went on for several thousand years from the time the glaciers receded.

With the arrival of the railway and essentially the extension of the world economic system in the 1880s through railways and shipping, we had an agrarian paradigm that has been superseded by resource extraction.

So in northern Alberta but also in Saskatchewan with potash, oil and other resources, our society and the wealth of our society is heavily dependent on those resources. So if peoples’ land and health is in the way, they are seen as an impediment of development.

That’s a huge part of what the Indigenous people of northern Alberta are facing. It’s almost a curse. They are surrounded by the second largest oil reserve in the world. That’s going to be a development for the next century, probably.

Honestly, I’m not really very hopeful with regard to how it’s all going to end. It’s very C02-intensive to extract. We as Canadians are getting a bad reputation around the world for the development of the oil sands, and the consequence is the loss of land, health and freedom of Indigenous people in northern Alberta and the Northwest Territories.

Thank you. I want to thank you for speaking with us. I want to thank Michael Welch and CKUW in Winnipeg for use of the studio. Congratulations on the book as well. I really hope it starts to make some waves, and I think it will start to appear more in the public, so thank you.

This interview was conducted on February 21 with thanks to Michael Welch and CKUW in Winnipeg.

James Daschuk is the author of Clearing the Plains. Daschuck is an assistant professor in the faculty of kinesiology and health studies at the University of Regina. Matthew Brett is a social justice activist and worker at Canadian Dimension magazine.

This book review originally appeared on Canadian Dimension and is reprinted with permission.