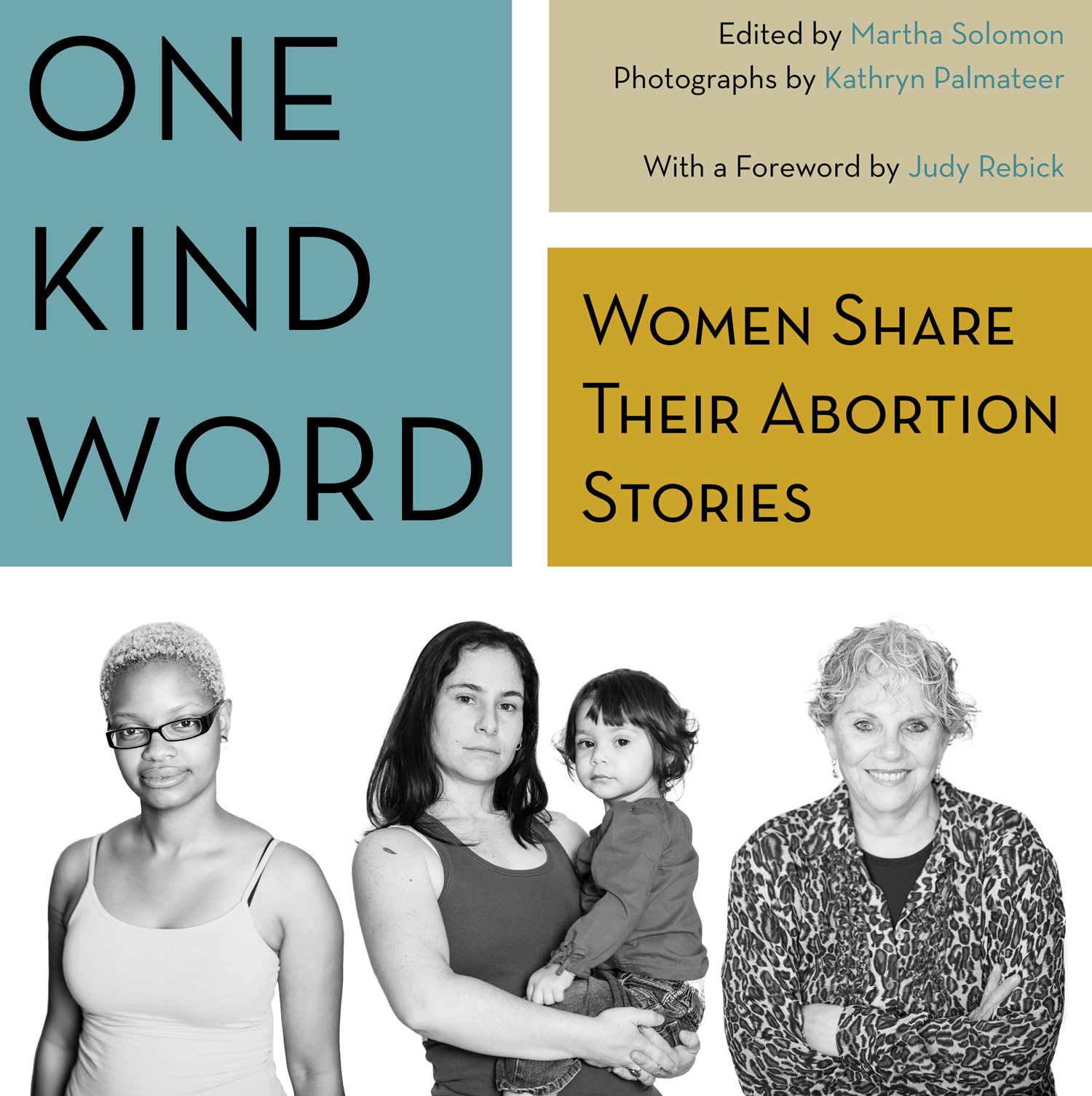

One Kind Word: Women Share Their Abortion Stories is exactly what the subtitle suggests: a selection of portraits and accounts of women who have had abortions in Canada, collected by photographer Kathryn Palmateer and editor Martha Solomon.

The title comes from Lori, the last woman of the collection, who says of her abortion, “The support I would have appreciated: one kind word from anyone.”

Lori’s wish is echoed through many of the experiences shared by many of the women in this collection who perceive a lack of kindness and respect extended to women who seek an abortion in Canada.

One woman, Sheila, recounts a doctor asking if she wanted an abortion because she didn’t love her boyfriend; another, Tabatha, recalls being lectured by a nurse about her “reckless behaviour” in front of other patients.

Their stories come from different eras. Some before the 1988 Morgentaler decision, when women seeking abortions had to make their case to a panel of physicians (“Therapeutic Abortion Committees”). Some when provinces allowed abortion but required parental consent if the woman was a minor. Some today when abortion should be widely available.

These stories convey varied emotions: relief, fear, shame, anxiety, elation. But none of the women included regret their choice.

They differ widely in age, ethnicity, circumstance, but they are united in a refusal to be silenced or shamed for their choice. They are willing to put their names and faces to their experiences. This shouldn’t be a bold choice in a country that struck down abortion restrictions more than a quarter-century ago, a country in which one in three women will have an abortion by age 50 — but it is.

Canada’s ongoing reproductive rights struggle

The attacks on abortion rights have been ceaseless throughout Canadian history, although tactics evolve and adapt to public opinion: scarlet letters and shaming women over premarital sex have mostly given way to tenuous pseudoscientific arguments about “personhood” and the misleading appropriation of terminologies that evoke medical expertise (“partial birth abortion,” “post-abortion syndrome”) and women’s rights (“pro-life feminism”) while being informed by neither.

Decades of research across countries with varying degrees of legal restriction and access to abortion has found that making abortions harder to get doesn’t make them more rare, just more dangerous.

Likewise, peer-reviewed research has debunked associations between abortions and breast cancer, disproved the existence of a “post abortion syndrome” and found that that fetal pain is not possible before 24 weeks.

Nevertheless, abortion opponents seem resolutely uninterested in history, logic or science, and continue to push tirelessly for a country in which it is more difficult for women to get a safe, timely, legal abortion.

While Canadians, in general, are in favour of legal abortion, abortion opponents exploit the points of contention, like abortions late in pregnancy or gender selection, with provocative strawman examples (“A woman can legally get an abortion at nine months in Canada!”), which are designed to chip away at public support and erode women’s rights bit by bit, by sensationalizing the cases that make even pro-choice Canadians flinch.

If anti-abortion opponents really believe that all fetal life is sacred — that each fetus is a person whose right to live is more important than a pregnant woman’s right to self-determination — then it shouldn’t matter whether or not the fetus was conceived through rape, or if the mother’s life is endangered by the pregnancy.

But only the most strident anti-abortion types — a minority of the minority — advocate for this no-exceptions position. The rest capitulate to social mores, painting women who get abortions as callous, irresponsible, promiscuous, bad mothers — demonstrating that their concern is less about the fetus and more about controlling and punishing the woman.

A recent article on Florida’s system of appointing judges to determine whether minors can have an abortion without parental consent demonstrates this: multiple teenage girls, desperate to have an abortion, are told by a judge that they aren’t “mature enough” to make that choice — the disturbing subtext being that there is a higher standard for women who opt out of motherhood than for those who are forced into it.

‘Bad’ abortions vs ‘good’ abortions

The result of this clamour and theatrical hand-wringing over “bad” abortions by anti-choice activists (with the long-term goal, of course, of preventing any abortions) is a heightened public judgement of women who get abortions, the idea that women who are seeking this legal, ubiquitous procedure should uphold a certain moral standard.

But anti-abortion activists aren’t the only ones at fault here.

The vast majority of Canadians support access to abortion; however, only about half Canadians support abortion “in all circumstances“; the other half are concerned about abortions late in pregnancy. Nevermind that less than one per cent of all abortions in Canada are performed after 20 weeks, and nearly all for medical reasons.

Some pro-choice people tend to squirm when confronted with examples that could be seized on by the anti-abortion contingent: a woman who has had multiple abortions, but doesn’t use contraception; a woman who waits until the second trimester to see a physician; a woman who chooses to abort a fetus that has a non-life-threatening disability.

We’re guilty, too, of wanting to hush up the narratives that endanger public support that aren’t thoroughly sympathetic. We don’t want them throwing fuel on the anti-abortion fire, or — secretly — we don’t want them to make us uncomfortable by being regular women facing difficult, personal choices, rather than perfect sympathetic figures.

But if pro-choice Canadians truly believe that it’s a woman’s right to choose, then we shouldn’t care who that woman is or what her circumstances are.

It’s for that reason that One Kind Word is necessary, not just for those who are ambivalent or opposed to abortion, but for those who consider themselves pro-choice and yet participate in the silencing of women’s voices and experiences.

Under pressure

Individual women, acutely aware of the ongoing battle over their rights, are pressured to behave a certain way as patients, and then a certain way as women who have had abortions.

In Leslie Jamieson’s essay ‘The Empathy Exams‘, she writes about answering a nurse’s questions at her abortion appointment with the spectre of judgement hanging over them: “Tell her you feel sad but you know it’s the right choice, because this seems like the right thing to say, even though it’s a lie.”

Women are made to feel shame about abortions, and they are made to feel as though they don’t deserve to ask for sympathy or experience complicated emotions.

In the words of on woman Jaime: “I’m furious that I am not able to grieve without feeling like I will be misinterpreted politically. I am very angry that politics dictate how I should be feeling about my decision.”

Another woman, Kayleigh, sharing her experience of getting an abortion, compares the silence around abortion to the discomfort she perceives as a person with a disability: “I always took [other people’s] silence as an indicator that I should be ashamed of my difference, which I found insulting and untrue. Now, I take the silence around abortion the same way.”

This is helpful to no one: not Canadians at large, who need to come to grips with the fact that abortions happen a lot more frequently than one might think from the dearth of more books like One Kind Word, and certainly not to women who have had abortions and deserve empathy, solidarity, safe spaces to share their diverse experiences of a common event.

The trouble with how choice is framed in Canadian discussions of abortion is we equate it with freedom. We suggest that by choosing, women give up their rights to have complex feelings, to experience relief and elation as well as sadness and guilt, because they chose their path.

Jamieson writes, “Mine was the kind of pain that comes without a perpetrator. Everything was happening because of my body or because of a choice I’d made. I needed something from the world I didn’t know how to ask for.”

One Kind Word is a reminder that there are many experiences of abortion and ways to feel about it.

It’s underlying message is that we may not relate to every woman’s experience, or understand it, but we don’t need to. We just need to listen to them, without trying to shoehorn their experience into a comforting narrative or a political talking point, or demanding their reasons and justifications. We need to take the burden of asking for care and compassion off of them, and offer it freely for a change.

We need to trust them and believe them when they say, it was my choice. It was the right choice.

Michelle Reid is a health researcher, magazine editor and occasional writer living in Vancouver, BC. She is a proud member of the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation but doesn’t use that as an excuse to wear headdresses to music festivals. She tweets frequently as @ponymalta