Of all the lessons that the architects of neoliberalism have imparted over the past four decades, perhaps the most insidious was the idea that there would not be losers along the road to 21st-century progress. Instead, the prospect of the end of history brought with it the promise that all of us would be winners.

The future was frictionless. Or so the political logic went.

Today, that logic has worn thin around the edges. The reality of climate breakdown has exposed the idea that a better, human future was inevitable for what it was: a new-fangled political cover to mask the realities of capitalist wealth concentration. A better future — or any future at all, it seems — must be fought for, vigorously.

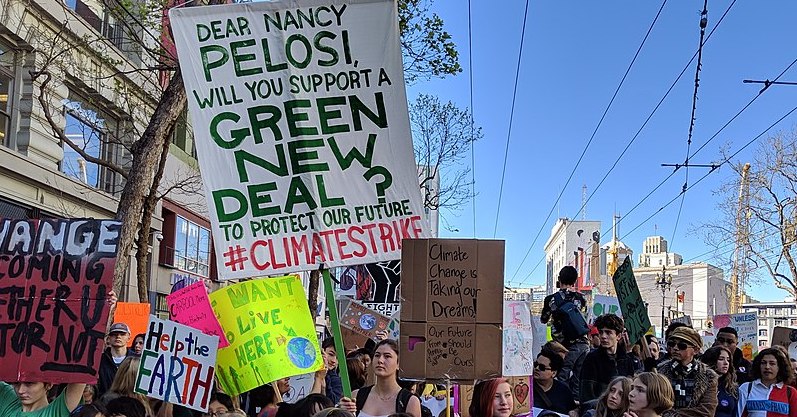

If the very fact of climate change has mainstreamed the trickery of this neoliberal logic, then the authors of A Planet to Win (Kate Aronoff, Alyssa Battistoni, Daniel Aldana Cohen and Thea Riofrancos, all prominent climate activists and scholars) put it to rest once and for all. Within the context of late-stage capitalism and climate collapse, the authors argue that the activist left must popularize a new moral and political calculus, one aimed at building a world where all people can live a good life. For Aronoff, Battistoni, Cohen and Riofrancos, this means fighting for — and winning — a radical Green New Deal.

The authors are careful to distinguish between a faux Green New Deal, which focuses on crafting narrow climate policy behind closed doors, and a radical Green New Deal, which broadens climate policy and “leans in” to the “inevitable” intersections of economic, social and environmental issues. “What we really need is a new political economy,” they assert in the introduction. Incremental change might have been possible, had we started three decades ago. But with just a narrow sliver of time left before we lock in devastating levels of carbon emissions, nothing short of a radical Green New Deal will do.

While the broad stroke components of the radical Green New Deal the authors outline are fairly straightforward — an eco-socialist vision that moves beyond New Deal era public works projects to include public ownership, a fundamental reimagining of the world of work, and new forms of democratic control — the book’s real innovation lies in its reminder that the end-game isn’t merely to transition away from the extractive systems that brought us fossil fuels and dirty energy. The goal is to build a just, democratic, caring world.

There is a difference between the oft-invoked vision of industrial retooling towards green technologies and the authors’ vision of a Green New Deal. The former is a transitional strategy, while the latter involves establishing an entirely new society. Building a new world can’t happen without an initial transition, of course, and the authors spend ample time describing the processes that might get us there in time.

But they put equal emphasis on what comes next: living in it. This reminder runs throughout the book, echoed in small but vital details. The book’s suggestion that former coal mines might be turned into educational and recreational sites for people to learn about labour and environmental history, for example, helps to flesh out what daily life could look like under their radical Green New Deal.

Policymakers often focus on the technical elements of climate adaptation, but A Planet To Win takes a different approach. While we do need to invest in research and new technologies, the authors point out that we already have ample solutions and resources to make the transition happen. Public dollars line the pockets of the fossil fuel industry and the banks that finance them; the world’s greatest polluter, the U.S. military; and other industries, like Big Pharma, that put profit over people. We’re not missing the technical know-how or the money, what we’re missing is political will. A Planet To Win supplies us with a potent set of political lessons to inform the movement for a radical Green New Deal.

Of these lessons, perhaps the most important is their case for abandoning the neoliberal focus on attaining elite consensus, which has straightjacketed climate policy in both the U.S. and Canada, and embracing a politics of visceral public popularity. This sort of left populism requires identifying the enemy — the fossil fuel industry — and building a mass movement aimed not at appeasing our enemies, but winning.

As the authors rightly point out, the labour movement historically provided society with a keen awareness of what transformative, radical change might look like, what “winning” took, and what people can accomplish through collective action. The four-decade assault on workers and unions — carried out not just by conservatives parties on both sides of the border, but by liberal politicians, too — has dampened our sense not just of what’s possible, but how to get there.

Building momentum around a radical Green New Deal must draw on these strategies and, in doing so, restore power to workers. That the labor movement has tried-and-true strategies to offer — one of the book’s chapters is called “Strike for Sunshine” — does not prevent the authors from arguing that a radical Green New Deal must also redefine and expand our concept of “work.” A federal jobs guarantee, which would offer a good union job to anyone who wants one, is just one piece of the puzzle. A Green New Deal would also involve massive public investment in the arts, free university and college education, and support for low-carbon work, such as care work, which is today often underpaid or unpaid work done primarily by women and people of colour.

The authors also admit several blindspots, including questions about food security and agriculture. But the book’s greatest accomplishment is its willingness to challenge the neoliberal consensus around what kind of change should be considered pragmatic.

After decades of outright climate denial, we now face obstacles and roadblocks to climate action because our political leaders want to approach adaptation incrementally, through tweaks and patchwork policy-making, to achieve consensus without taking on the industries actively ruining our planet.

It’s this logic that has led to our increased investments in renewables to simply increase the overall energy supply, instead of actually displacing dirty energy. We don’t win without wholeheartedly taking on the enemy. The authors show that, in the context of climate breakdown, these kinds of transformative, radical changes are, in fact, the pragmatic ones.

The title itself — A Planet to Win — implies both a set of material facts to be changed (or, rather, won) and, through the use of an indefinite article, reminds us of the imaginary we must collectively create. Nothing is guaranteed. We need to figure out what we’re fighting for, and how we want to fight for it. The book accomplishes both: the authors weave the “what” with the “how” so gracefully that the book reads as much like a lyrical manifesto as it does an Alinskian organizing manual.

A Planet to Win concludes with promising set of freedoms that are both positive (freedom to move, freedom to live) and negative (freedom from fear, freedom from domination, freedom from toil). These “freedoms” are meant to guide us through the uncertainty of transition and keep our movements moored. “The future is coming at us fast — but we still have the chance to shape it. We have nothing to lose, and a planet to win,” the authors write.

We should all be taking notes.

Sophia Reuss is rabble.ca’s assistant editor.