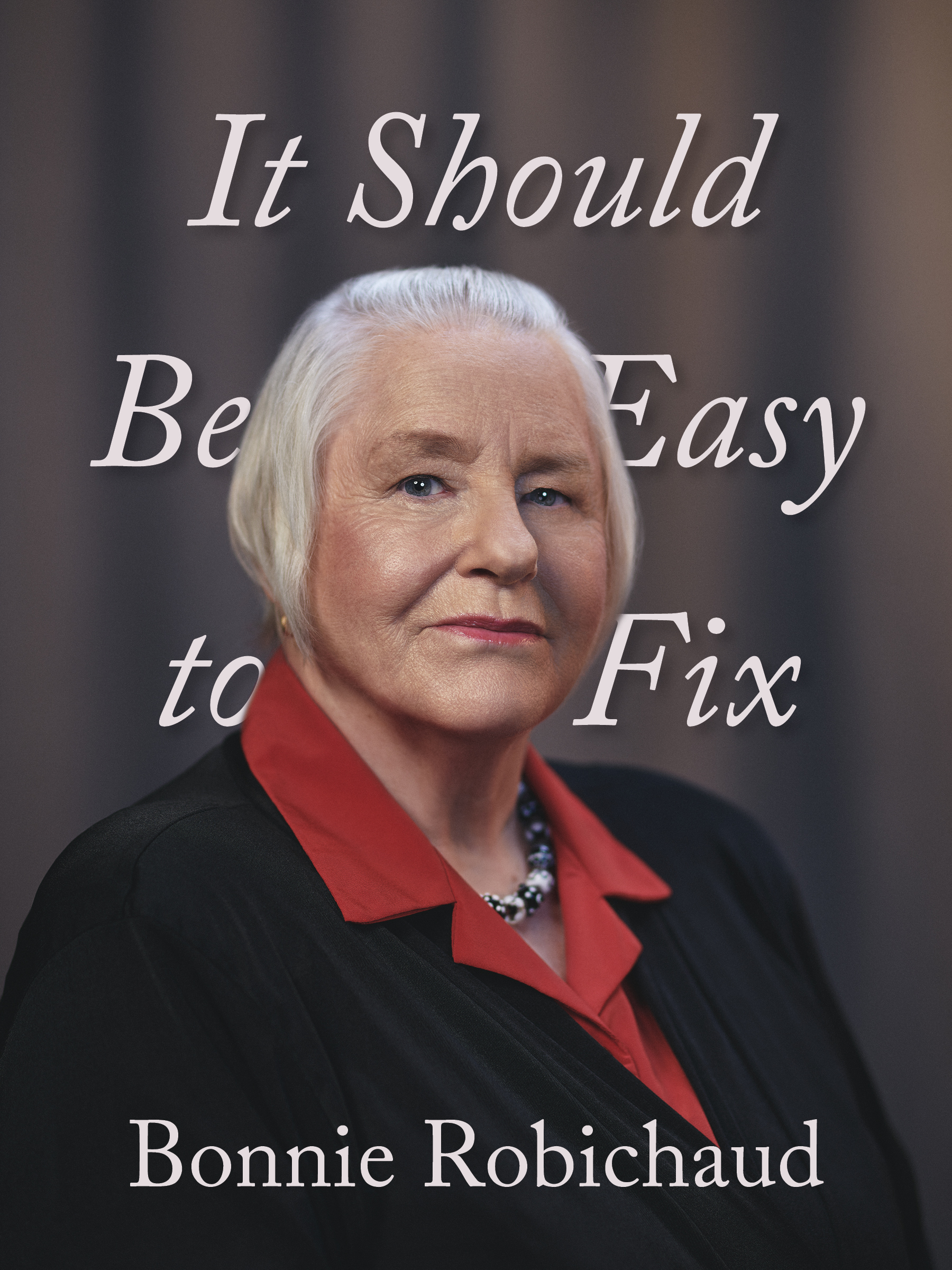

In It Should Be Easy to Fix, union activist and public speaker Bonnie Robichaud reflects on the decade-long legal battle to hold employers responsible for sexual harassment in their workplaces.

The title of the book harkens back to Robichaud’s response to a high ranking military officer who said nobody had ever complained about sexual harassment in the workplace.

“Well then,” she said more than 40 years ago, “it should be easy to fix.”

Robichaud was no stranger to workplace discrimination. As a young woman, she lost her job after experiencing a miscarriage before subsequently being offered a transfer on the condition that she didn’t get pregnant for two years. Suffice it to say, the employer had to find someone new.

So when Robichaud found herself experiencing sexual harassment during her probation period at the Department of National Defence, she knew she had reason to fear her employer.

Shortly after she started her new job as a cleaner, her new boss began making advances that made Robichaud not just uncomfortable, but fearful for her job and safety.

In Jan. 1980, Robichaud filed a complaint with the Canadian Human Rights Commission, arguing she had been “sexually harassed, discriminated against, and intimidated by her employer … and that her supervisor was the person who had sexually assaulted her.”

At issue in the Supreme Court case was “whether or not an employer is responsible for the unauthorized discriminatory acts of its employees in the course of their employment under the Canadian Human Rights Act.”

Her case specifically targeted the harassment allowed by her managers rather than the harassment itself.

A legacy born out of “the lowest point” of Robichaud’s life

In an interview with rabble.ca, Robichaud explained It Should Be Easy to Fix was a long time coming, with the first draft initially completed in 1989.

It wasn’t until Robichaud heard from a union colleague working on a video for the Public Service Alliance of Canada’s 50th anniversary in 2016 found Robichaud’s original draft that the idea to publish her memoir resurfaced.

“I wanted to write it because, up to that point, there was zero responsibility for the employer to do anything about sexual harassment,” Robichaud explained. “There was still a lot of work to be done there.”

In her memoir, Robichaud reflects on the fact that her legacy—changing federal laws around sexual harassment in the workplace—also happened to be “the lowest point of my life.” Robichaud also candidly described how unwanted attention can begin as an annoyance, before it “relentlessly escalate[s] to the point that it dominates your life.”

“It was not my goal in life to do this. My goal in life was to raise my beautiful children, and spend quality time with them. That was my goal since I was about six years old—to love them—and I’ve never changed my mind,” Robichaud said. “This got, shall we say, thrust on me. And I wasn’t going to give up.”

Robichaud reflected on her time writing the book, noting it was difficult but necessary.

“It put me back in the same place I was then, but still, the book needed to be written,” she said. “If we don’t write our history, it won’t be done.”

“We cannot make social change if nobody knows what it is that needs changing”

In her memoir, Robichaud noted that her filing to the Canadian Human Rights Commission marked the first complaint of sexual assault referred for inquiry since their inception in 1977.

At one point during her decade-long fight, Robichaud was reassigned to a school at CFB North Bay, this time working under a female boss who considered Robichaud’s former boss “a real gentlemen.” The job taught Robichaud another harsh lesson: that having a female boss gave no guarantee of solidarity.

Another time, she was experiencing unwanted and inappropriate comments from another male superior. When she took it to the Public Service Commission, she was dealt a devastating blow: you can only make one sexual harassment complaint per lifetime, at least back in the 1980s.

“We cannot make social change if nobody knows what it is that needs changing,” she wrote.

Robichaud took her story to CTV’s long-running news series W5 in the March 11, 1984 episode. One year later, she decided to take back the narrative and created the Bonnie Robichaud Defence Committee Newsletter. The publication would eventually be put on hiatus in an agreement to continue her case.

In her memoir, Robichaud wrote of reading Margaret Atwood’s then-newly published The Handmaid’s Tale. Reading that book, she had a realization: that while the women in Atwood’s story didn’t have a choice, Robichaud still had the right to appeal.

Robichaud found herself being forced to relive her experience over and over again. She called it “voyeuristic” telling a room of men at her union about being sexually assaulted. While it would’ve been easy for Robichaud to give up—and did her superiors ever try—she wrote that the more resistance she received, the more determined she became to fight back.

The ruling from the Supreme Court of Canada applied to all federally regulated workplaces across Canada. However, while sexual harassment in the workplace should have been easy to fix, Robichaud is troubled by just how little has changed in the workforce for women.

“We’re more knowledgeable now. We know that women are not responsible for being sexually harassed and there may be employers who do take responsibility for it,” Robichaud said.

While there’s still so much work to do in holding perpetrators of sexualized violence in the workplace accountable, Robichaud is pleased to see the shift in public opinion that followed the #MeToo movement.

“One really important thing is that if women no longer stay silent, they can at least talk to each other about it and bring it more out in the open,” she said.

But the cycle of sexual harassment in the workplace still carries on, often through non-disclosure agreements.

“All that [non-disclosure agreements do] is protect the employer and further harm the complainant,” she said. “I would never again sign a silence clause for anybody. It’s wrong.”