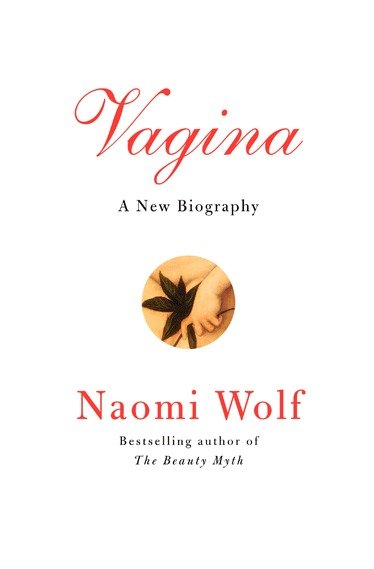

Naomi Wolf’s fall from grace within the feminist community has been well documented. First there was her baffling, victim-blamey defence of Julian Assange, and now she’s been taken to task by writer after writer for her generalizing, the-goddess-is-in-your-vagina take on female sexuality. After having read criticisms of her most recent publication Vagina, such as this from Suzanne Moore in the Guardian:

“My problem with Wolf is longstanding and is not about how she looks or climaxes — but it is about how she thinks, or rather doesn’t. She comes in a package that is marketed as feminism but is actually breathlessly written self-help.”

And this from Maia Szalavitz in Time Magazine:

“The brain and female sexuality are extremely complicated — and reducing them to simplistic formulations that deny women their humanity fails to do justice to either feminism or science. Properly contextualized, neuroscience can add to our knowledge of sexuality, but not if it’s twisted to support sexist ideas about women as ‘animals’ who are so addicted to love that they become zombies.”

And, of course, Ariel Levy’s cutting review:

“[Wolf] started her career (and, some have argued, another wave of feminism) with a fresh iteration of an old idea: that our culture had reduced women to their bodies. Many feminists, then, may be perplexed to find Wolf, in her eighth book, situating the essence of the female being right back where it started: in the body, in one particular place…

…The vagina is no longer an orifice within a woman; the woman is now a support mechanism for the vagina. Anger the vagina and the woman will have no choice but to become a harpy. Biology is destiny once again.”

I was already well-versed in how badly Wolf mucked up her attempt at writing a book about her supposedly groundbreaking discovery that, gasp! the vagina and the brain work in congruence … Just like how, you know, the process of eating a muffin or painting our fingernails is necessarily connected to our brain. If our vaginas weren’t connected to our brains we wouldn’t have any sensation at all down there.

So I must admit that even before cracking the front cover, I expected not to like the book. My preconceptions didn’t disappoint. I immediately littered the introduction with eyerolls and scribbled notes in the sidelines that consisted of little more than variations on the word ‘barf.’

Wolf approaches the subject of female sexuality and the vagina from a personal perspective, which can work well for these types of explorations. As women, our personal experiences naturally shape our understandings of our relationships to our bodies and to sexual pleasure. But she does so in a way that applies her personal experience to all women. And yet, the truth is that all women are not Naomi Wolf.

I couldn’t help but get the sense that she had simply run out of ideas.

Wolf’s incentive for writing the book begins with her concern that, though she continues to have great sex and tons of orgasms, the orgasms she was having weren’t wowing her. “Colors were just colors,” she laments. “It was like a horror movie.” OH the horror! Wolf’s regular orgasms weren’t brightening the leaves on trees or making her as chatty as usual. Forgive me for saying so, but big whoop.

Considering the number of women who either have a difficult time orgasming, or simply never do, Wolf’s ‘problem’ struck me as insensitive at least. At most, reeking of privilege. As Salavitz said to me in an interview: “Talk about first world problems.”

All that said, as someone who has experienced challenges in the orgasm department, there were parts of Vagina I very much appreciated. I know that many women can relate to the feeling of frustration and even desperation that is experienced when we can’t reach orgasm. We have all been socialized in a world that is largely defined by a male perspective; naturally sex hasn’t escaped that framing. One of the consequences of this male-centred understanding of sexuality is that that we learn sex is linear, as Wolf points out. “Orgasms are seen as the ‘goal’ of sex in our culture,” she writes, which means that if we aren’t experiencing orgasms, we often feel, and our partners often feel, that there is something amiss.

While it’s always seemed relatively obvious that men’s orgasms are a little more, let’s say, straightforward, than women’s, what Wolf discovered in her research was that the female pelvic neural network is extremely complex and varies from woman to woman. So much so that orgasms, Wolf writes, are “completely unique for every individual woman on earth — no two women are alike.”

A couple of months ago, after telling a friend that, as much as I hated to reinforce stereotypes about women being exceedingly complicated, for me, orgasms had never been easy or straightforward. His response was this:

“What, the set of factors that triggers your orgasm is complicated? Labyrinthine even? Almost like a complex set of riddles, codes, and puzzles that make the end result almost impossible to predict except on a slow, step by step basis? And any man who successfully navigates the maze is more likely to become your long-term partner, even if you didn’t find him worthy at first?”

Sigh. Yes. Like that.

And Vagina makes a similar case. What she gets right is that all women are ‘wired’ differently. This discovery could possibly go a long way in terms of resolving a lot of the shame women experience around not being able to come, or come easily. She also argues that women are hardwired to become attached, “addicted” even, to “the person with the right touch to activate your unique neural network.”

“The truth is,” she writes, “if he or she didn’t … touch you in ways that suited your unique needs to be touched, or make you come satisfyingly — you wouldn’t care that much if he or she never called again.” Which I’m not actually convinced is at all true. While the idea that we become chemically attached to those who are able to navigate the ‘maze’ that ends in orgasm makes sense, it doesn’t explain equally valid and stimulating sexless relationships and it implies that women’s choices when it comes to relationships out of their control.

Wolf goes on to make a number out-there claims about the connection between women’s creativity, productivity and decision-making ability with sexual satisfaction, providing evidence in the form of female artists past, from George Eliot to Georigia O’Keefe who she claims experienced noticeable increases in creative flow and productivity that was in direct relation to their “sexual flowering.” Odd, because, in my experience, I seem unable to get anything done whilst in the throes of new love or lust. Elation, love, and orgasms are notorious for inspiring irrationality, cheese, and lovesick cliches. If you want proof, look no further than my diary.

But, hey that’s me.

And isn’t that the whole problem with Wolf’s Vagina? She takes her own experience, which is perfectly valid as far as personal experiences go, and sets out on a mission to prove that it is universally applicable to all women. She attaches femininity to our orgasms, which erases and ignores a lot of women who are doing perfectly fine minus sex. What of the orgasmless woman? Is she destined to a life of bland colours and lacking in creative drive? Depressed and unable to make a decision to save her life?

Wolf could have avoided all the critiques she’s been subjected to over Vagina had she answered her own question differently. When she asks: “was this an insight potentially generalizable to all women?” her answer, like all feminists who know better, should have been “obviously not.”

How to Be a Woman

by Caitlin Moran (Harper Perennial, 2012; $17.99)

Caitlin Moran’s How to Be a Woman has most commonly been viewed as “fun.” And indeed, the author succeeded in publishing a light, I’m-every-woman read that aims to revitalize what Moran sees as a movement in desperate need of re-branding.

One reviewer wrote recently: “Reading her first book, How to Be a Woman is probably the closest I will come to a religious experience.” And though Moran’s working class roots and her messy honesty make her relatable and likeable, I can’t say I felt the same awe that others expressed.

Jumping from the “stripping is bad because women do it for money not for fun” to “burlesque is good because those women don’t even need the money!” argument and other such gaps in logic that ignore the whole “female bodies on display for the male gaze” factor jarred me into a cynicism that stuck for the remainder of the book.

On CBC Radio’s Q, Moran tells interviewer Jian Ghomeshi that she’s “pro- pornography.” She explains to him that there’s a “big argument about it in feminism” and seems a bit miffed at a movement she says has “rules” about what one can and cannot like. “I just thought that if you said you were a feminist you believe men were equal to women, but apparently not. If you are a feminist you are not allowed to like pornography.”

Because she sees her persona as a comedic one, it’s difficult to know when to take her completely seriously. Another way to look at this would be to see Moran’s jokey style as a way to avoid making solid arguments and as a defense against critique.

So while her views on pornography — that it’s “just people having sex” and that it doesn’t “damage” her to watch it might be a light oversimplification (as much of the book is — a light, oversimplification), she’s also quite serious. Her belief is that mainstream pornography is a problem, as it encourages women to remove all of their pubic hair (which she sees as a very bad thing), because it’s created this trend of referring to vaginas as “pussies” (which she doesn’t like), and because it’s all the same — a “porn monoculture,” she calls it.

But her solution, which is simply more variety in porn, fails to address that silly little multi-billion dollar industry that survives and thrives on a tidal wave of patriarchal-capitalism. A stronger critique than simply “more variety” is needed.

While Moran may well want to make feminism an easy sell, dictating that certain acts or social phenomenons are acceptable while others are not, without providing a solid foundation for those conclusions isn’t necessarily useful in terms of making an argument for feminism.

And this is where Moran fails. She wants to make feminism palatable and so she oversimplifies. And I understand that to a certain extent. How to be a Woman was not intended to be a heavy academic book about feminism. Part memoir, part “feminism is for everyone!” Moran just wants people to get on board. Why wouldn’t a woman want to be a feminist, she asks? Or, as she puts it: “What do you think feminism is, ladies? What part of ‘liberation for women’ is not for you? Is it freedom to vote? The right not to be owned by the man you marry? ‘Vogue,’ by Madonna? Jeans?” While voting and jeans are wonderful things, today’s feminist movement is about much more than suffrage and Moran’s comfy clothes. If that were the case, post-feminism would be a real thing.

In an effort to sell her brand of feminism that says this is just about doing what you want and feeling good about it, she oversimplifies to the point of confusion. Stripping is BAD, burlesque is GOOD. Pubic hair is GOOD, g-strings are BAD. As much as I appreciate that she advocates for real, contradictory, imperfect women — I myself being a real, contradictory, imperfect woman, I don’t see Moran’s understanding of feminism as being about much more than her own personal preferences. Sure, I hate stilettos and brazilians as much as the next person, but I also see the connection between women’s learned desire to be pretty objects manifested in burlesque, a culture that very much supports the uncomfortable shoes and underwear fad Moran deplores.

She wants women to be comfortable with their bodies, their shoes, and their abortions. And that’s great. But in terms of a movement, we need, also, to be making some bigger connections.

It seems as though one of the biggest selling points for Moran’s book is her humour, and even that was lucklustre. Tina Fey did a far better job writing a comedic, feminism-is-ok! type of book with Bossypants than Moran and doesn’t try to take on arguments she isn’t prepared to back up.

Unfortunately, I get the distinct feeling that both Wolf and Moran’s recent publications are representative of the current climate of feminism today. Less “feminism is for everyone,” and more “feminism is for me.”

Meghan Murphy is a writer from Vancouver, B.C. Her website is Feminist Current.