We’re headed back into a wave.

If you’ve ever been caught up in an undertow, you know the feeling. It pulls you down into the water until the next wave spins you around, curls you up and spits you out onto the sand. But you’re not out of the water yet. Before you can get your bearings, the next cycle is upon you and you’re pulled back under, sputtering, turning, becoming even more disoriented. It takes a few cycles until you figure out your exit point; the one moment in the flow pattern when your own strength outmatches the relentless pounding of the ocean.

It feels very much like in this pandemic, we’ve missed our exit point.

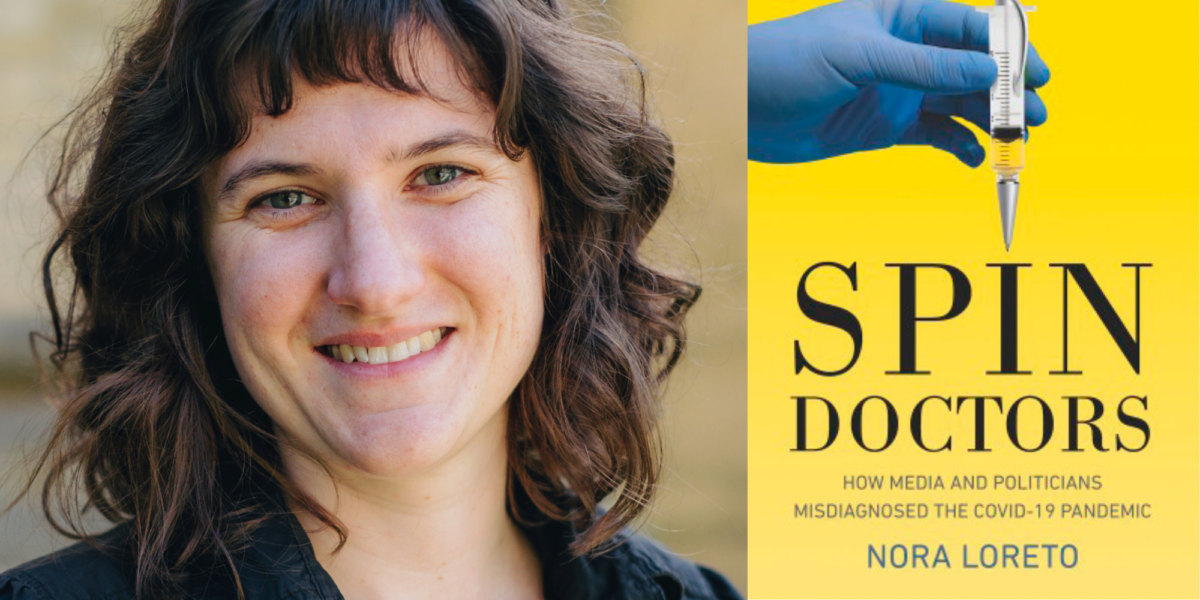

Or, as Nora Loreto, author of Spin Doctors: How Media and Politicians Misdiagnosed the COVID-19 Pandemic, put it during her appearance on the Canadaland Shortcuts podcast yesterday: “it feels like Groundhog Day.” The Bill Murray kind.

The Omicron variant is here and spreading rapidly within our borders, yet the main response by the federal government is to close borders and impose racist travel restrictions. Media tells us once again — at the brink of another holiday season — to prepare for the worst, yet fails to offer any hope for a future in which we won’t be living in fear. Many provincial governments, including the one here in Ontario, again tell us that the spread of the pandemic is up to each of us as individuals and not, in fact, up to them, our elected representatives who are paid to enact public policy in our best interest. The premier of Alberta specifically cited “personal responsibility” when pressed about his decision to loosen COVID-19 restrictions prior to the holidays.

It feels hopeless. It feels unending. It feels like I will never not feel anxious in a crowd or with a group of unmasked friends. It feels like we’ve failed. And, if you listen to the government releases or media coverage, (which, as Loreto describes in her book, are too often one and the same), you haven’t done enough. You have to do more. It’s all your fault.

It’s not.

What Loreto describes in her book is a multi-system failure. Canadian media is in system failure. Long-term care is in system failure. Capitalism is in system failure at the expense of the working class. Industry takes advantage of the failure by refusing to increase wages on pace with inflation, by eroding worker’s rights and providing care to society’s most vulnerable as cheaply as possible. As neoliberalism is wont to do, individuals are blamed for the spiral.

Government takes advantage of the failure by privatizing essential services like care in the interest of balanced budgets, making fluffed up funding announcements and providing a plug that is two sizes too small for the drain. The spiral continues.

Of course individual politicians and journalists should indeed do some reflecting on the way they’ve framed this pandemic and its peripheral issues and how that framing dictates public policy. Indeed, much of Loreto’s book is dedicated to unpacking this framing and how it has left us in a state of constant panic without anywhere constructive to direct our nervous energy.

Canadian media went into this pandemic with slim resources, overworked and underpaid newsrooms and dwindling advertisers. Over the last two years, Canadian newsrooms have continued to shrink, demanding more from fewer staff members and outsourcing the rest to underpaid freelancers. It’s understandable, then, how many people found themselves living in a sort of information fog throughout this pandemic, at a time when clear, deep journalism was most necessary.

As Loreto points out, official government statements are far too often taken at face value, repackaged in plain language and disseminated as journalism. The numbers we hear about – and are starting to hear about quite loudly once again, as Omicron cases climb – are never just numbers. Data can never be neutral, and yet throughout this pandemic, (and beyond, frankly) there has been an assumption from much of Canadian media that: 1. government data can be accepted at face value, and; 2. that data is presented by government in an arms-length, impartial way.

Consider how governments shared information about COVID-19 outbreaks and deaths in long-term care across provinces:

“B.C. reported long-term care, retirement residences and assisted living facilities, more or less regularly during the first wave, but then stopped for most of the second wave, reporting this figure’s overall total instead, and only once per week. On January 7, 2021, the B.C. Centre for Disease Control resumed regular weekly reports. They didn’t include hospital outbreaks. Alberta reported this information to media, and not consistently. If journalists didn’t write about the information, it would not be reported publicly for a specific day. Saskatchewan didn’t report anything; outbreak and death information came through journalists who uncovered outbreak information by reporting on residences individually. Manitoba reported long-term care, retirement residences, assisted living and hospital outbreaks daily, but not cumulatively. Ontario reported long-term care daily and cumulatively, but not retirement residences, adult assisted living or hospital outbreaks. Some of Ontario’s 34 public health units reported shelters, retirement residences and adult assisted living, like Toronto, Ottawa, Waterloo, Peel and Halton, but some did not, like Middlesex-London, Durham or Windsor-Essex. In Quebec, the province with the best overall data, CHSLDS, retirement residences and assisted living were reported daily, though not cumulatively per residence. Through the Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ) however, data about total death by location of residence was easy to access for any day of the year. And New Brunswick and Nova Scotia both relied more on journalists to push the information out, though deaths were so low that the stories received widespread media coverage when they happened.”

All of this meant that reporting on long-term care outbreaks across the country was inconsistent, incomplete and lacking definition. Loreto meticulously points out these gaps in government information and media reporting and, where she can, fills them in. (Loreto co-authored a report last June released by the Royal Society of Canada that estimated Canada’s death toll at the time was actually double what the government numbers were claiming).

Much of the missing, incomplete or distorted data that Loreto challenges in Spin Doctors is data about groups of people who were left most vulnerable to the virus. Seniors, those with disabilities, workers and Black, Indigenous and people of colour – not to mention those who occupy the spaces where those identities intersect – continue to shoulder a hugely disproportionate burden.

Loreto’s book offers a detailed look at the gaps. She doesn’t offer us a quick fix or a solution to the problem that is our current, grinding socio-economic system. She does offer up, on a platter, a map for accountability.

“During the pandemic, Canadians needed unflinching investigations as well as daily reports that mentioned things like how many residents were sharing rooms together in an outbreak or how much money a company stood to lose if they were forced to shut down during an outbreak,” she writes at the end of her last chapter, which focusses distinctly on the media’s role in the mismanagement of the pandemic – a theme that runs throughout the book.

She goes on:

“This information could have shown people, for example, why there was such resistance to closing down large congregant work settings, even though the evidence was overwhelming that that was one critical measure for pandemic mitigation. But most news stayed close to the official line, rarely straying from the expectations and limits imposed on them by a corporate media whose owners preferred to fire people in the middle of a pandemic to boost their bottom line than endure a year of lower profits or debt in the service of providing information for the common good.”

So far, it doesn’t seem like much is going to change as the Omicron variant sweeps government messaging and media with sentiments of panic, sensationalism, and the same, strange, off-base policy decisions we’ve seen the last several waves.

“The only tool people are using is to scare people and hopefully therefore scare politicians into doing something. Which they will not,” Loreto said today on Canadaland. “There is this giant black hole of information related to Omicron that is related to our day-to-day lives.”

We’re back to being bashed against the shore by the waves. Groundhog Day, indeed.