For many millennia, the anguished and rugged liminal geography that Coll Thrush examines in his brilliant new book, Wrecked, (the Pacific coastline from what is now called British Columbia south to Coos Bay in southern Oregon,) was the traditional territory of a number of Indigenous nations, including the Tla-O-Qui-Aht, the Makah, the Chehailis, the Chinook and the Siuslaw. From 1693 on, more than 2,000 ships from European and colonial empires of trade and settlement came to grief along this shoreline, which came to be known to colonizers as “The Graveyard of the Pacific.”

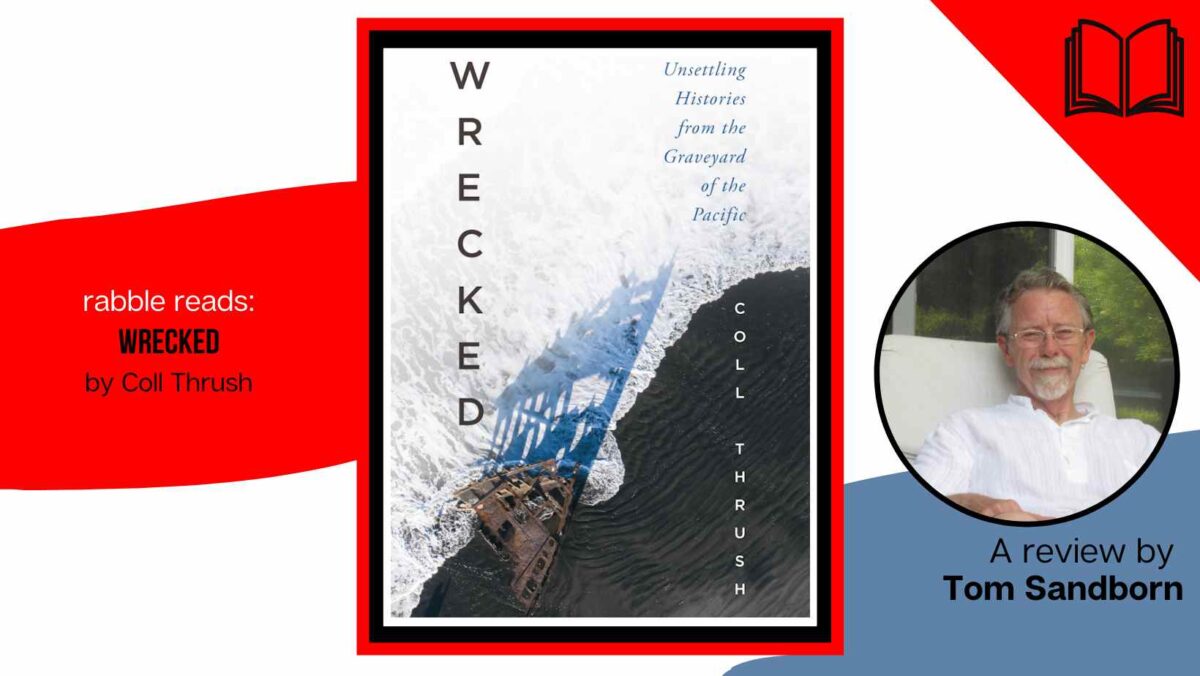

Thrush is a professor of history at the University of BC and the author of two well received previous books, Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place and Indigenous London: Native Travelers at the Heart of Empire. (Full disclosure: I know Thrush and his husband from the pre-covid days when we all hung out at the same gym.)

In the preface to his current work, Thrush clearly situates himself as a settler-ancestry kid fascinated by the shipwrecks he would see on family visits to the coast and as a committed ally of Indigenous peoples With those two perspectives in mind, he describes his book as a “view from the shore,” and what a view it is!

The author moves from intimate personal memories of the role that shipwrecks played in his childhood experience and imagination to exhaustive archival research and profound ethical reflection, not only about the too often violent and disrespectful treatment of Indigenous nations by the crews of the settler ships that haunted the Graveyard but also about similar disrespect among settler journalists, politicians and some of his fellow historians. This is a profound and challenging text, full of insights and intellectual rigor, but never hectoring or polemic in tone. What drives the book and makes it such a satisfying read is the wonderful human stories it has to tell.

These stories include the loss in 1693 of the Spanish galleon Santo Cristo de Burgos, laden with Chinese porcelain and silk, fabrics from India and beeswax. For years the only trace of this lost ship and its cargo was to be found in Indigenous memory and settler legends about a ghost ship that disappeared into hidden sea caves beneath mount Neahkahnie, the highest mountain on the Graveyard shoreline. But in 2022 a National Geographic expedition penetrated the sea cave beneath the mountain and retrieved spars from the ship crafted from hardwood grown only in the Philippines, and historians learned yet another lesson about the importance of taking Indigenous oral traditions seriously.

Two other significant maritime mishaps that Thrush addresses in this Pacific Rim picaresque (although, as he notes, neither are “exactly shipwrecks”) are the demise of the Boston in 1803 and the Tonquin in 1811. The Boston crew insulted and abused the Nuu-chah-nulth people led by hawilth Maquinna at Nootka Sound. When fighting broke out, the Nuu-chah-nulth warriors prevailed and killed nearly all the crew, leaving only two survivors. One of them, John Jewitt, lived among his captors for several years before reconnecting with white “civilization” and authoring a book about his time on the coast.

In another “trading” negotiation that went wrong in 1811, Jonathan Thorn, the captain of the Tonquin ( pride of John Jacob Astor’s resource exploitation enterprise up and down the coast) insulted a chief. The Indigenous warriors prevailed again, until, in a series of events that remain murky to historians, the gunpowder stores onboard exploded, sinking Astor’s ship. Both these events became part of the settler narrative about dangerous “savages,” a narrative that justified genocidal violence against Indigenous nations like the shelling of an Ahousaht village in 1864.

Indigenous law gave the nations along the shoreline title to anything that came ashore, whether grounded whales or shipwrecked sailing ships, a view that white settlers and colonizers did not share, needless to say. While Thrush has many tales to tell about shipwreck survivors being rescued by Indigenous people, he makes clear that the counter narrative of “evil natives” mistreating the sacrosanct properties and bodies of the white intruders tended to take up more space in settler discourse and served to rationalize conquest and displacement of the original inhabitants of the coast.

This is an important book, full of fascinating stories and cogent, useful ethical reflections. In a time when Canada’s partial and not yet adequate attempt at truth and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples is under attack from the political Right and honored more in rhetoric than in action by many in the political centre, it is part of the truth we need to face and engage before true reconciliation can occur.

As the author recently told an interviewer:

“ I think Indigenous history and Indigenous studies—which are not necessarily the same thing—are engaged with silence on multiple levels. First, there is the ongoing work to overcome the erasures of settler colonialism, which seek to render Indigenous peoples and polities invisible or absent. It’s more than just a matter of articulating that Indigenous people were actors in the past; it’s a matter of showing how Indigenous peoples and Indigeneity were critical to the most important aspects of colonial history, from their military and political influence to more subtle processes such as the formation of whiteness and ideas about “liberty.”

Highly recommended.