The labour market is in much worse shape than the official 7.3 per cent unemployment rate implies. The latest evidence for this proposition is a miserable report on employment and earnings from Statistics Canada.

Further to Andrew Jackson’s post on the release, most media coverage of this report focuses on year-over-year measures of growth in hourly wages and weekly wages. And on this basis, the news was grim: year-over-year growth in weekly earnings (considering both hourly and salaried workers) slowed to 1.1 per cent in September, down dramatically from their 3 per cent clip earlier this year, and the slowest increase in almost 2 years. Average hourly wages are also decelerating quickly: to 2.5 per cent year-over-year in September, down from 5 per cent as recently as April. (Weekly earnings perform worse than hourly wages right now, for two reasons: the number of hours worked has declined, and salaried workers have fared worse this year than hourly workers.)

However, the situation is actually considerably worse than these year-over-year numbers imply. Year-over-year comparisons (often used for series which exhibit strong seasonal patterns) are like looking one year backward in the rear-view mirror. Shifts in direction of the series are not fully reflected until many months after they happen.

Statistics Canada provides seasonally adjusted versions of both series, however, so it is both appropriate and more informative to compare month-to-month trends rather than year-over-year data. On this basis, it is clear that wage inflation is not just slowing down; rather, we are already tipping over into nominal wage deflation.

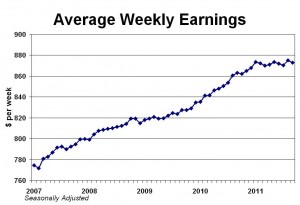

In nominal terms, average weekly earnings have been stagnant or slightly declining all year, and are now lower than they were in January (see first figure below). Since consumer prices rose 2.4 per cent during the same period, workers have taken a significant hit to their real incomes (as Andrew’s post stresses). But possibly even more dangerous is the potential for falling nominal earnings. That could ultimately feed into deflation in broader prices (especially once energy prices turn down, which is likely if the global economy stalls again), with potentially explosive consequences for consumer spending, debt burdens, and macroeconomic stability.

Average hourly wages also declined in September (see second figure), and more rapidly. Indeed, they’ve been falling at an annualized rate of almost 2 per cent since June. Already the decline in nominal employment incomes (especially measured by weekly earnings) is worse than occurred during even the worst months of the 2008-09 recession.

If in fact Canada is now entering another recession, the labour market is starting from a much weaker position than was the case in autumn 2008. That means the economic and social consequences will be much more harsh.

The risk of broad deflation, originating in a depressed labour market, provides a very strong macroeconomic argument for the role of unions. By preventing a downward cycle of wages and prices rooted in the desperation of workers, unions help to anchor the nominal price level and stabilize macroeconomic conditions. In this regard, the Harper government’s holy crusade against labour rights is doubly perverse: apart from further undermining the economic position of workers, it raises the risks of deflation and depression for the whole economy. Mr. Harper and Ms. Raitt should be careful what they wish for.

Jim Stanford is an economist with CAW. This article was first posted on The Progressive Economics Forum.