“There is a wise saying that goes like this: A real gentleman never discusses women he’s broken up with or how much tax he’s paid.”

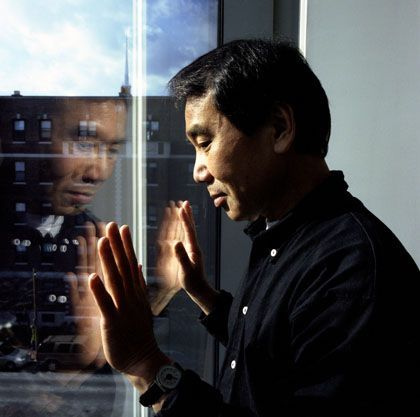

– Haruki Murakami

When one goes back to a book and rereads it, there can be a radical incongruity between the past and present experience of the text. Suddenly aspects of the book that were previously hidden, or absent, appear to be written in the largest font on the page. One of baseball’s deadliest sluggers, Reggie Jackson, said after hitting three home runs in a game in the 1977 World Series, that the ball on this day looked as big as a melon, meaning that it was impossible for him not to hit it. Analogously, on some days certain paragraphs appear as melons whereas previously they sped by too fast for the mind to record. This experience tells us that reading is actually a form of writing, that is, of constructing an interpretation or illusion, revising it or tearing it down, and then — if one has the vitality — establishing not simply a new reading but a more complex, encompassing one out of the debris of the previous.

A writer who regularly produces the feeling of incongruity upon re-reading him, that is, the recognition of how much one writes into the text, is Haruki Murakami. Murakami is Japan’s most famous writer and he has won every major Japanese literary award. As well, he is one of the world’s most popular novelists: his books have been translated into over 40 languages and for the past few years there has been regular speculation that he will win the Nobel Prize for Literature. His works include The Wild Sheep Chase, 1Q84, and The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle — the latter often cited as his best. One never knows what to expect when turning the page of one of his books. Murakami has said that he himself often has no idea what will emerge next; the initial draft of his novels are written without an outline: “If there is a murder case as the first thing, I don’t know who the killer is. I write the book because I would like to find out. If I know who the killer is, there’s no purpose to writing the story.” Despite the various drafts that he composes, the final version always retains an ungraspable, unknowable shimmer.

Along with his prolific writing production he is also unexpectedly a long-distance runner. He has completed a marathon every year since he first started writing novels as a full-time occupation. The first sentence of his apparently flippant memoir What I Talk About When I Talk About Running comments that there is a wise saying that a real gentleman never discusses women he’s broken up with or how much tax he’s paid. The next sentences exclaim, “Actually this is a total lie. I just made it up. Sorry! But if there really were such a saying, I think that one more condition for being a gentleman would be keeping quiet about what you do to stay healthy.” Murakami then goes on to point out that he is not a real gentleman and thus begins his explanation of why running is an integral condition of his craft as a writer.

While his stories are the strangest of any contemporary novelist that I have read — tales of solitary individuals who are obsessed with ears, cats, refrigerators, sofas, beer, elephants, music and love — his own life as he documents in his memoir is severely regimented. Murakami goes to bed every night at 10 p.m. and wakes up between 4 and 5 a.m. every day. He writes for five to six hours and then runs six miles as training for his annual marathon. He has held to this schedule for almost every day for the past 30 years and states that this regime is necessary in order to deploy the physical and emotional endurance required to write creatively.

He notes, and this is a part of the text that I missed in my first reading years ago, that composing novels is essentially an unhealthy type of work. Writing, he believes, forces the writer to confront a toxin that resides within oneself and within all of humanity. Thus a substantial commitment to writing becomes a dangerous obligation and every writer has to find a way to confront the threat that this poison possesses. Murakami explains that many writers lose their capacity to write great novels as they get older because they lose the stamina that is required to incessantly confront the venom that lurks within humanity.

Murakami’s toxin metaphor applies not only to writers but to activists and theorists as well. Progressive action and thought forces one to face the contaminant that has grown within society. While progressives, unlike conservatives, do not believe that humans are essentially characterized by greed or violence, we do recognize that social structures and cultures have encouraged us all to think and act in authoritarian, self-interested ways. An honest, regular confrontation with society’s ignorant violence can lead to a worn, tired quality bereft of the vitality necessary for social and political innovation. While Murakami the writer armours his mind by disciplining his body, how do progressives — who have dedicated their lives to human progress — steel their hearts over the long haul when continuously encountering, challenging and reflecting on numerous forms of aggression?

Thomas Ponniah was a Lecturer on Social Studies and Assistant Director of Studies at Harvard University from 2003-2011. He remains an affiliate of Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and an Associate of the Department of African and African-American Studies.

Photo: Chan Hsun-Chih/Flickr