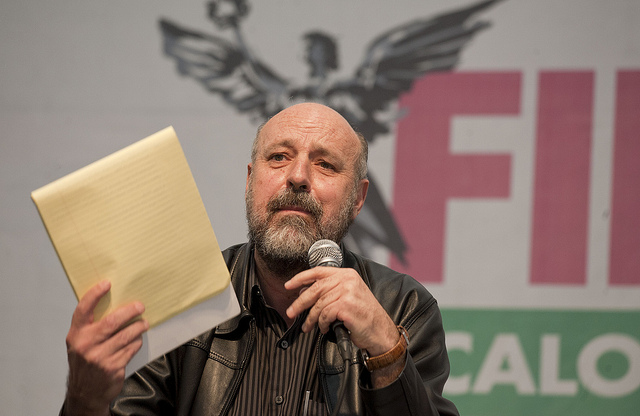

Luis Hernandez Navarro was in Toronto this week to speak about the crisis in Mexico after the deaths and kidnappings of student teachers last fall. He’s an eminent journalist and opinion editor at La Jornada, Mexico’s second largest daily. It’s well to the left of leftish papers elsewhere like the Star or Guardian.

He’s exhaustively reported those events in the small city of Iguala in the turbulent state of Guerrero. The students were from one of Mexico’s fabled rural teachers’ colleges, which have been crucial to social progress since the revolution 100 years ago. They were exploring ways to travel to Mexico City to mark the anniversary of a 1968 massacre of student protesters. That included “fishing” for busses which they would “borrow,” and then return. It’s a bit loosey-goosey but so has social order been during the “drug wars” of the last decade. Probably over 120,000 killed; 23,000-30,000 missing. People tolerate informal arrangements. But six of the students were killed in encounters with police and military; 43 disappeared, or were kidnapped. It wasn’t the first or last time but for some reason it resonated nationally and sparked outrage.

It’s routinely mysterious what ignites social explosions, though you can always speculate afterward. In Tunisia in 2010, a street vendor, humiliated by police, set himself afire and the Arab Spring immediately followed. He wasn’t the first or last either. It’s one reason I drifted from my early Marxist leanings: you just can’t “analyze” history well enough to anticipate or manipulate it.

Luis says (in retrospect) that the Iguala events were “the last straw.” Mexico has been deteriorating from a “narco-state” — strong central government colluding with crime cartels — to a “mafia state” — numerous political and criminal elements battling each other chaotically. What resonated from Iguala wasn’t the brutal deaths (face of one student ripped off his skull) but the missing. You can’t stop hoping they’re still alive, though it’s hopeless. And the authorities do nothing, or less: they cover it up, generating more rage. Half of Guerrero’s municipalities have now been seized and governed by local, unofficial groups.

There’s also the resonance of the rural teachers’ colleges. They were part of the two key elements in the original revolution: free universal education and land reform. They brought literacy and hygiene to peasants and still do — though they’ve been under attack since the ’68 protest. They have a legendary status.

And there’s this: in Mexico the revolution never dies away. In the U.S. their revolution is a faded memory, preserved mainly by laughable “re-enactors.” In Canada our relation to our past is so tenuous we must be constantly reminded to recall it. (Remember the War of 1812? Remember last year’s commemoration of it?) In Mexico, history — especially the revolution — always seems right there.

Luis says the momentum from last fall appears to have stalled. The struggle is now between memory and forgetting of that particular event, though others will surely take their place. I asked what keeps him going. He sighed and said, “Right now I am feeling great anger.” He used the word indignation, an interesting term that has recurred in social justice movements lately. I think its appeal is that it contains the term for dignity. Tunisians called their movement the dignity revolution though media tried to label it the “jasmine revolution.”

But he said youth give him hope. In Mexico City, dentistry students asked him to speak about Iguala, to describe “what wasn’t on TV.” They thanked him for telling them what they already felt but didn’t fully know. It’s surprising where you can find hope for a nobler future: dentists. Take note, Dalhousie.

Then he asked why this interested me. Without a ready answer, I said too glibly, Because nothing human is alien to me. Aha, he replied, “Carlos Marx said that too. You’re not as far from him as you think.” It’s true, there was a 19th-century version of the lightning round and Marx gave that line, in the original Latin, as his favourite saying. And glibness aside, I believe it. You don’t have to be an expert or linguist to find things that are common and even inspiring in distant settings. Besides, we’re cellmates, us and the Mexicans, in NAFTA.

This column was first published in the Toronto Star.