Charles Dickens wasn’t thinking of the twenty-first century when he penned these opening lines of A Tale of Two Cities, but they work as a pretty good caption for the current era, and for the decisive season of contract bargaining and strikes facing auto workers on both sides of the US/Canada border this fall. For the first time in decades, the United Auto Workers (UAW) in the US and Unifor in Canada were in a position to take strike action against the auto industry’s Big Three: Ford, General Motors and Stellantis (the recently formed multinational that owns 14 brands around the world, including Chrysler and Jeep) at the same time.

Auto workers could be poised to make labour history again, as they did in the heroic era of sit down strikes and factory seizures in the 1930s.

But some observers on the left worry that this historic opportunity for workers is going to be squandered in a flurry of compromise and sell out, and meanwhile the business press is uttering shrill cries of alarm about how any serious work stoppage in the industry will be bad for “the economy,” (AKA corporate profits.) Little is heard from these pro-business pundits about whether annual CEO pay at the Big Three, up 40 per cent in the last four years and ranging between $21 million and $29 million dollars last year, is a similar threat to the economy. Whether viewed from the left or the right, the situation in the North American auto industry is a very big deal indeed.

The two unions involved share a complex history. Canada’s Unifor, the country’s largest private sector union, with over 300,000 members across the country, represents over 18,000 auto workers at Big Three plants in Canada. Unionized auto workers in Canada split from the UAW in 1985 to form the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW), which in turn merged in 2013 with the Canadian Energy and Paperworkers Union (CEP) to form Unifor. Unifor left the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) in 2018 in a dispute over Unifor raids launched against other CLC member unions, while the UAW remains a member of the American Federation of Labor–Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), the umbrella organization that links most American unions.

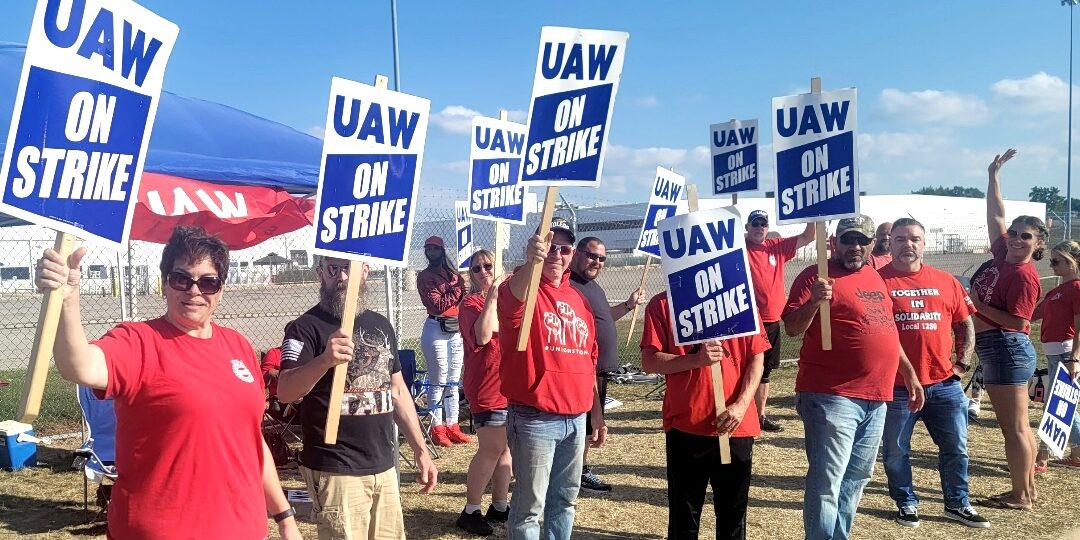

The UAW contract with the Big Three expired on September 14 of this year, and the American union, which represents nearly 150,000 American autoworkers, announced a new strike tactic it called “stand up strikes.” This involved selective work stoppages at one plant from each of the Big Three producers, a marked departure from the “pattern bargaining” tactic that has been traditional in auto disputes. In pattern bargaining, the union first chooses one company and focuses on getting a contract with that employer, then turns its attention to other employers with the first agreement serving as a pattern for the next agreements. In Canada, Unifor has maintained the pattern bargaining tactic, focusing first on Ford. After granting the employer an extra day of bargaining past what had been seen as a strike deadline, Unifor announced on September 19 it had reached a tentative agreement with Ford, with membership voting to approve the contract over the weekend..

Meanwhile, south of the border, the UAW announced on September 22 that it was expanding “stand up” strike action to shut down 38 more General Motors and Stellantis plants across 20 states. Ford is noticeably missing from the list of new actions announced, and UAW head Shawn Fain indicated that enough progress had been made in Ford negotiations that the union was not expanding its actions at Ford, yet. In a statement posted on the UAW website, Fain said:

“As you know, we gave our Members Demands to the company two months ago. They wasted a whole month failing to respond. But there has been movement. In particular, we’ve made real progress at Ford. We’re not there yet, but I want you to see the direction that Ford is going, and what we think that means for our contract fight. At Ford, Rawsonville Components and Sterling Axle employees will now be on the same wage scale as assembly workers. We have eliminated that entire wage tier. At Ford, we have officially reinstated the Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA_ that was suspended in 2009.”

Meanwhile, going into a weekend in which Canadian auto workers will vote on a contract with Ford recommended by Unifor bargainers and UAW pickets go up at more US auto plants, while leaving most UAW members on the job, the resolution of the current disputes remains uncertain. Leadership of both unions have been criticized by observers on both the right and the left, with the reliably pro-business Wall Street Journal quoted an op-ed by General Motors President Mark Reuss that accused the UAW of spreading myths about what the companies can afford, and the World Socialist Website called for more militance and less compromise from union leadership, saying “The trade union bureaucracies on both sides of the Canada-US border are pulling out all the stops to sabotage the contract struggles of nearly 170,000 auto workers across North America.”

What many observers to the left of Unifor and UAW leadership would like to see is a continent-wide strike of auto workers in Canada, the US and Mexico with militant demands to shift some of the profits from the industry away from already overpaid CEOs to the workers who actually build the cars and generate the profits. This is a compelling vision, and it is hard to fault it on the grounds of simple fairness. We are unlikely to see such a tri-national campaign this autumn, but the predictably flawed contracts most likely to emerge from this round of contract talks may well make more workers sympathetic to this more radical vision in the future.