Change the conversation, support rabble.ca today.

For much of human history the young have had little political or cultural power; societies were ruled by a gerontocracy that was underpinned by the belief that elders should govern. This of course changed in the period between the end of World War II and the early 1970s. Youth — from adolescence to the mid-20s — became an age of significant, independent social influence.

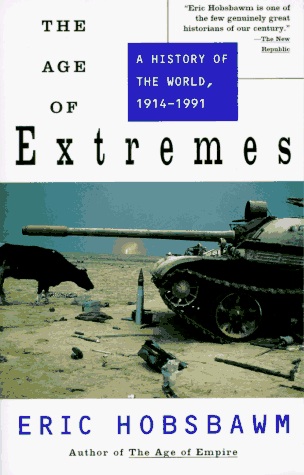

In The Age of Extremes the historian Eric Hobsbawm argued that the new emerging youth culture of the wealthy countries demonstrated three significant qualities. First, the juvenescent culture became prevalent in the wealthy nations because it articulated a cohesive sector of technical power. It represented a unique section of society because the velocity of technological development gave young people a significant advantage over the older generation. The latter had not grown up with computers and software thus reversing traditional roles: the knowledge of the young seemed more socially, culturally and economically significant than that of the old.

Second, the new youth culture was not only prevalent in the rich countries of the world but also became internationalist with numerous aspects such as blue jeans and rock music becoming ubiquitous symbols. The extension of the years of education and the agglomeration of large groups of young people in universities amplified the impact of youth culture — especially the American version. Importantly and perhaps necessarily this youth culture emerged during the period of the United States’ greatest economic prosperity. The music industry discovered the purchasing power of young people in the 1950s: in 1955 record sales were $277 million, $600 million in 1959 and $2 billion in 1970. Rock music became the anthem of the new global youth culture and it was underpinned by the consumer dollars it offered to corporations.

Third, the young and to some degree others no longer perceived youth as a developmental stage en route to adulthood but as the culmination of life. An example of this was the reverence shown to film and rock stars who died young and thus stayed youthful forever: James Dean, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix, to name a few. As with athletes and musicians it was understood that life before 30 was the most vibrant, successful and spontaneously pure time of existence, and the years after would never again be as energetic, fulfilling or honest.

Demographic trends tells us that the cult of youth — in North America — will continue to have impact but without the same magnitude. The original purveyors of youth culture, the baby boomers, with better health care, greater personal awareness of nutrition and exercise and a substantial commitment to life-long learning, are living longer while families are having fewer children. In the future the boomers will constitute a larger percentage of the voting population while the majority of the young will continue to ignore electoral politics. As the elders cease to work they will not fade into retirement homes, bridge clubs and gardening but will instead revive the activist impulses of their youth. The generation that brought us May 1968 has been the most influential, politically sophisticated one of the last 60 years. They will use a portion of their retirement time pursuing social change — or at least pursuing activism to fulfill their own needs — the benefits of which will also spread to the rest of society.

As it becomes clearer to business and policy-makers that many of the newest forms of information technology are teaching people to become more distracted, unaware and inefficient — as every teacher who has watched students compulsively check email during class and every employer who has watched their employees waste time on Facebook understands — the social and economic value of many new forms of information technology will decline. The significance of the talents of the younger generation will diminish and we will return to a more familiar historical pattern, that is, a gerontocracy, albeit one that has now assimilated, through pension funds, easy-to-use laptops, continuing education courses, yoga sessions and ginseng — the comparative advantages of the young.

Thomas Ponniah was a Lecturer on Social Studies and Assistant Director of Studies at Harvard University from 2003-2011. He remains an affiliate of Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and an Associate of the Department of African and African-American Studies.