Sexual liberation was a core principle of the social movements of the 1960s. The desire to emancipate desire was central to the belief that a new society and a new experience could be created. The United States’ LGBTQ (lesbian/gay/bisexual/trans/queer) movements are often described as having begun with the Stonewall Revolt in Greenwich Village in New York City. The rebellion consisted of hundreds of gays resisting a police raid over the course of three days. In The Power of Identity, the sociologist Manuel Castells notes that there were 50 organizations for sexual minorities throughout the U.S. in 1969; after Stonewall the number rapidly increased, reaching 800 organizations by 1973. From that point on it took a mere 40 years, negligible by historical standards, for a U.S. president to declare that he supported the right to same-sex marriage. As readers of this column know, I have praised President Obama’s backing for the legalization of same-sex marriage: it is the most courageous affirmation of equal rights on the part of any president since Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. There are of course many criticisms of same-sex marriage from conservatives, usually claiming to draw on nature or religion, but they are rarely scientifically accurate or logically consistent. A much more persuasive argument comes from those on the left who contend that the current LGBTQ agenda — oriented as it is by a quest for equality by assimilation — is actually hampering the long-term pursuit of freedom.

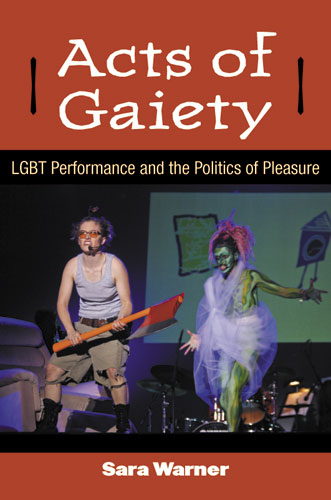

One of the most thoughtful articulations of this critique comes from Sara Warner, a professor at Cornell University, who proposes in her new book Acts of Gaiety: LGBT Performance and the Politics of Pleasure (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012) that movements for sexual liberation need to reconstruct their agendas based on a reactivation of the themes, practices, feelings and visions of their more radical predecessors. The book reflects on various forms of performance, “acts of gaiety,” by drama queens, jesters and guerrilla activists such as Valerie Solanas’ “Theater of the Ludicrous,” zap actions by lesbian feminists protesting marriage, Jill Johnston’s anarchic forms of civil disobedience, the musical theatre adaption of Diane DiMassa’s ‘zine Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist, and Five Lesbian Brothers’ Oedipus at Palm Springs. Warner’s hope is that the visionary writers, artists and performers profiled in her text will inspire the public to turn away from the current LGBTQ assimilationist agenda and instead move towards goals that are genuinely emancipatory.

Warner suggests that we are now witnessing the onset of what she calls “homoliberalism,” that is, an LGBTQ program that pursues mainstream inclusion such as the right to marry, to serve in the U.S. military, and to engage in capitalist enterprise. She argues that this is a set of political goals that, in contrast to the movements of the past, will demobilize, privatize and depoliticize sexual minorities while affirming the worst aspects of American consumer culture. The author notes that, a generation ago, “union organizing, nuclear disarmament, peace, urban renewal, prison activism, immigration reform, the environment, rape, abortion, domestic violence, protection and birth control topped the list of lesbian causes.” Today, LGBTQ communities — save a few remarkable exceptions — no longer make this intersectional model of freedom their priority. It is striking to witness how so many progressives can thoughtfully discuss their own particular agenda while being relatively ignorant or indifferent to the concerns of those outside their priorities. The logic of specialization which organizes the modern market and the state appears — at least in North America — to have also configured the imagination of the activists who resist it.

The triumph of neoliberalism, which occurred not with its conservative inception in the 1980s, but with its consolidation by liberal political parties like the Democratic Party in the USA, the Labour Party in Britain and the Liberals in Canada in the 1990s, has corresponded to the victory of assimilationist policies among formerly radical groups. Movements and individuals have abandoned social change and instead embraced integration: contemporary women, LGBTQ communities, and people of colour appear to desire membership in the U.S. establishment much more than they wish to alter it. This strategy may be understandable in light of the formidable forces opposing genuine transformation, but it is not prophetic. Warner should be applauded for her attempt to investigate the historical emergence of “homoliberalism” and to reanimate gaiety — in all its complexity, affection and aspiration — as a political value for those progressives whose eyes remain focused not just on the ebb and flow of the moment but on a grander possibility just over the horizon.

Thomas Ponniah is an Affiliate of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin America Studies and an Associate of the Department of African and African-American Studies at Harvard University.