Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

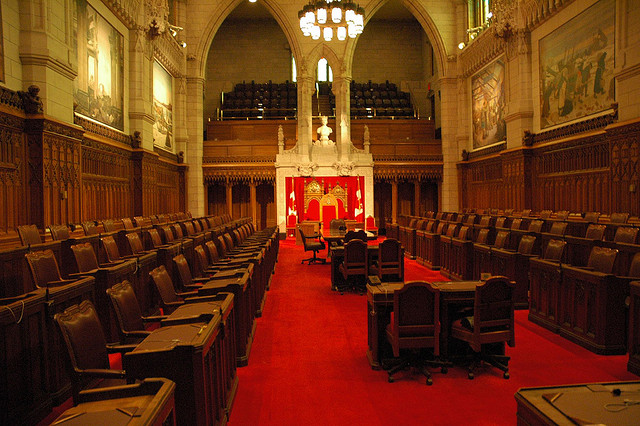

Have we given up on Senate reform? The debate seems to have drifted down into a muddle about how to fill 22 vacant seats.

This is not good enough. Let us remind ourselves of what the real scandal is. It’s the fact that the damn thing costs nearly $100 million a year to run — or nearly $1 million per senator — something largely lost amid the expenses scandals of this or that senator.

No matter how tangled are the constitutional knots hindering Senate reform, the process must begin with some sense of direction. Assuming we can’t get rid of it (more of that below), the ultimate goal should be to shave it down to a third or less of its present size. Start with reducing P.E.I.’s four senators to one, Nova Scotia’s 10 to three and keep doing the math across the country.

Next is the question of how to appoint senators. The Trudeau Liberals have set up an independent body to vet candidates for the 22 seats, but this is only scratching the surface, not to mention avoiding the real issue.

Let me tell you about an illuminating document I fell upon while contemplating all this. It’s a comparative study of upper chambers worldwide done at University College, London, England. (Google “upper chambers worldwide” and scroll down to “Second Chambers Overseas — University College, London”.) My takeaway from it is that, among upper houses the world over, we may well have the most ridiculous contraption.

At last count, there were 58 countries with upper houses out of some 178 national parliaments worldwide. In the 29-member OECD rich-country club, 17 have them.

Of the 58, 24 use various forms of direct election to choose members, while 17 have various forms of indirect election (for example, in Germany state governments choose them).

Meanwhile, 15 use direct appointment. And here’s the kicker: “However, the only Western industrial country having a wholly appointed upper house is Canada.” The other 14 are mostly small island nations, ex-British colonies in the Caribbean and elsewhere. There’s only one larger exception — Thailand — and it has the decency to require that appointees NOT be of the governing party.

Here’s what we should be aiming at: senators elected indirectly by society groups — municipalities, trade unions, trade associations, environmental groups; any body that can legitimately claim to represent a certain number of people. This would confer the legitimacy that senators now lack. It would be done with little fuss and bother. I’d expect that most provinces would have a couple of hundred or more of these.

The study adds that the main problem is “a lack of public respect for the Senate due to its appointed basis. It is not seen as democratically legitimate. Appointees are seen as recipients of cynical patronage — particularly as the prime minister only appoints from his own party.”

Well, yes, we know, but it’s interesting to hear someone else say it. Further, “the stigma of an appointed membership means much good work, for example on Senate committees, goes unnoticed.”

Here’s something else I learned. The Canadian Senate is “formally one of the most powerful second chambers in the world.” These powers are mostly constitutional, not least of which is the power to obstruct its own reform. The reason for this is that it’s modelled on the British House of Lords as it was in 1867, and it hasn’t changed since. Meanwhile, even that old clunker has moved on somewhat. In 1999, under duress, the Lords got rid of a couple of hundred hereditary seats, thanks largely to the sheer power of embarrassment, which may be the best hope for reforming the Canadian Senate as well.

As far as getting rid of the Senate, a poll commissioned by the Harper government last year found Canadians marginally in favour of keeping it. This is consistent with the study, which finds that there is “no clear trend worldwide either towards or away from two-chamber parliaments.” Some have been abolished since 1950, but these were in small unitary states — New Zealand, Denmark, Sweden and Iceland. They seem to be more of a fixed feature in large federal states, where the theory, at least, is of geographic and regional balance (although, as the study points out, in Canada, “despite its nominal provincial basis, there are no links at all between the Senate and provincial governments or parliaments”).

In other words, it’s a ridiculous thing at every level. If we can’t do anything about it, we’re just announcing our national impotence, not to mention blowing the better part of $100 million out the window every year.

This column was first published in the Chronicle Herald.

Photo: Adam Gerhard/flickr

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.