Here’s an enduring Canadian puzzle: why is it that raising taxes on the rich consistently polls exceptionally well — yet never makes it onto the political agenda?

Accordingly, it’s a sure bet that, when the Trudeau governments rolls out its budget next week, it won’t include a wealth tax.

But it should — and right now would be an unusually opportune moment to single out billionaires and megamillionaires for taxation.

That’s because, in a rare twist, the United States has pulled way ahead of Canada in getting the long-taboo issue of taxing the wealthy onto the agenda.

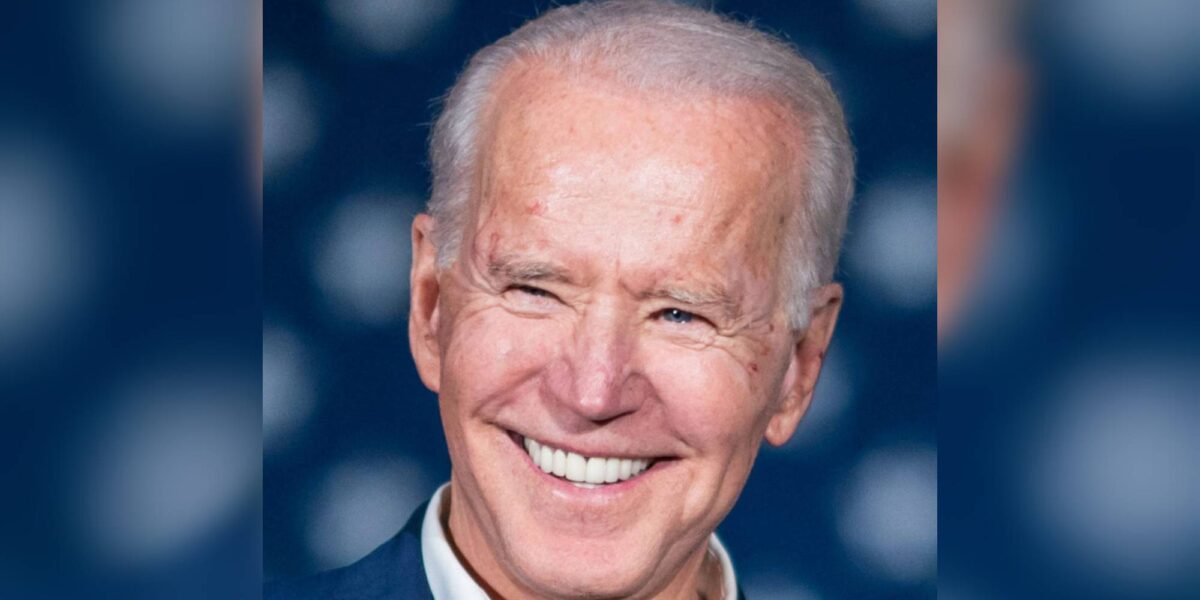

Joe Biden is proposing a number of measures, including an ambitious minimum tax on the wealthiest Americans — in the first big tax grab on the wealthy since Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980.

A fierce fight over taxing the wealthy looms in the U.S. The Democrats came close to passing a version of Biden’s minimum tax last year and could succeed if they regain control of Congress in 2024.

This trail-blazing by Biden, a centrist Democrat, should stiffen the spine of Canada’s strikingly timid “progressive” politicians. (While polls show more than 80 per cent of Canadians support a wealth tax, support is particularly strong among progressives.)

A wealth tax, aimed exclusively at Canadians with net assets above $10 million, could raise $28 billion a year — enough to seriously enhance key social welfare programs, according to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Those trying to avoid it would face a steep exit tax.

Yet, among major parties, the NDP alone advocates a wealth tax and leader Jagmeet Singh doesn’t talk much about it. Why didn’t he insist it be part of the NDP accord with the Liberals?

The Liberals are always keen to beef up their progressive credentials, so last year they brought in a “luxury tax,” which hit Canada’s superrich — with the force of a feather-pillow.

READ MORE: Biden’s green light to drill oil in Alaska threatens Indigenous Canadians

The tax doesn’t even attempt to address the real problem in taxing the wealthy — that, unlike the rest of us, they’re able to legally avoid income taxes. That’s because their wealth is largely held in corporate stock and, unless they sell stock and trigger a capital gain, no income tax applies.

So, rather than sell stock, the superrich can finance their lavish lifestyles by borrowing from banks, which happily lend them ample funds at very low rates — an option not available to those without a fortune to serve as collateral.

Biden’s minimum tax would close this gaping loophole by taxing the superrich on how much their shares appreciate in value, whether cashed in or not. This could add millions — even billions — of dollars a year to the tax bill of an ultra-wealthy American. (By comparison, Canada’s luxury tax might add thousands of dollars to the tax bill of an ultra-wealthy Canadian.)

Our prime minister lacks the boldness of mild-mannered Biden, so does nothing to grab a share of the immense wealth going straight to the top as Canada’s billionaires — and there are dozens of them, including some mega-billionaires — have seen their wealth grow by an astonishing 51 per cent since the pandemic began.

The prebudget debate here has been dominated by wealth-funded think tanks, such as the influential C.D. Howe Institute, which produced a Shadow Budget advocating a post-pandemic Canada with a lot less government spending — despite surging social needs.

Arguing that the cupboard is bare, the Howe’s Shadow Budget somehow overlooks the piles of largely untaxed money that the ultra-wealthy are sitting on, and instead suggests that any additional revenue needed should come from raising the GST — a move that would hit the middle class hardest.

As for tax increases on the wealthy, the Howe plan proposes, well, none. In fact, it advocates tax cuts that would benefit them.

The wealthy are a formidable interest group who play an enormous — although largely hidden — role in shaping the political agenda. Still, they’d have more trouble keeping a wealth tax off the agenda if our progressive politicians embraced the idea with the same gusto as the broad Canadian public.

This article was originally published in the Toronto Star.