The women’s soccer scandal in Paris is hardly the first time Canadians have cheated in order to win.

Canada’s greatest victory in international competition, the ’72 Canada-Russia series, was arguably won because Bobby Clarke swung his stick and broke the ankle of the ethereal Russian forward, Valeri Kharlamov. (It’s also arguable we won since Canada’s players, evoking general awe among their opponents, simply refused to quit.)

But Clarke’s hack was in another class from the drone flown over a New Zealand practice as instigated by Canada’s coaches. Clarke’s hack harked back to deep psychic recesses in the Canadian past. It was rooted in a colonial subservience learned from centuries of foreign masters, leading to our humble niceness (“Sorry!”) that was frequently counterbalanced by outbursts of violence in foreign wars (Vimy) or on the ice. It was national and visceral.

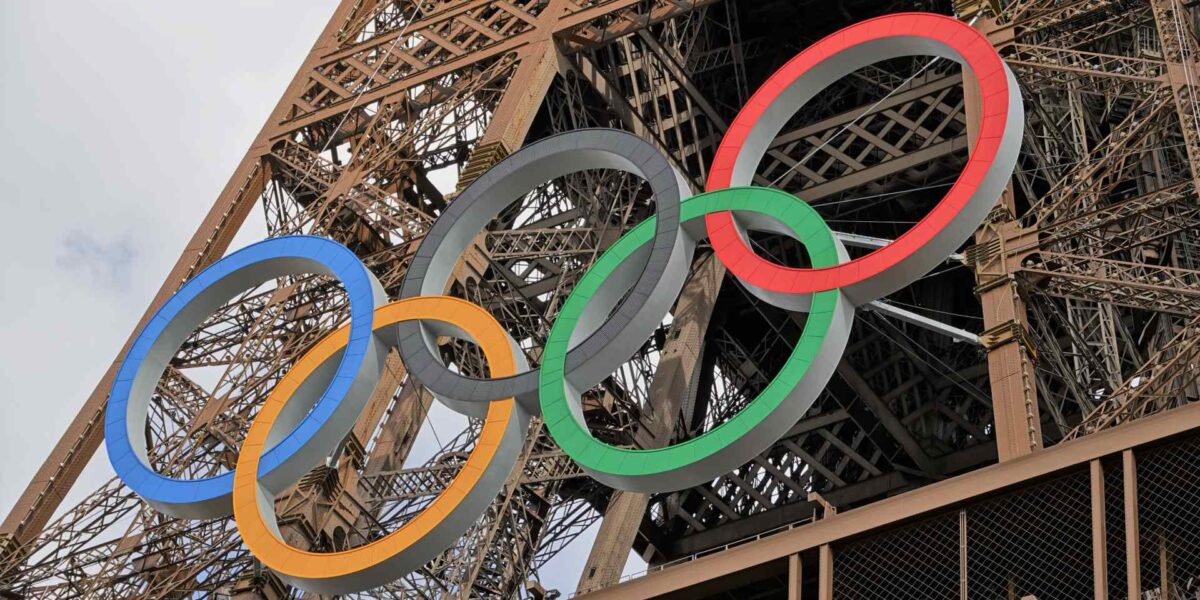

Not so with the plot of drones, which is economically and ideologically in tune with its times and has become the norm in international sports. It’s not uniquely Canadian, though in my opinion it’s related to a group called Own The Podium created in 2004 leading up to Vancouver’s 2010 Olympics. It was modelled on business competitiveness and the idea you can buy success anywhere, anytime. Own is a sporadically used sports expression but it was more common back then in right wing tropes like owning the libs — as in trolling or triggering them.

It also didn’t work.

We never owned the podium — check this morning’s list of medals — since podiums aren’t listed on stock exchanges. It’s a turgid metaphor that only really comports with those rich enough to think they can buy everything.

Winning has never been quintessential to satisfactions in sports though it clearly plays an important role. But so does almost winning — and losing. That’s how you test your mettle or simply learn what mettle means. Cathal Kelly wrote in the Globe & Mail after the Oilers defeat this spring: “They don’t sing songs about people who almost did something.” In fact, they do. Listen to Stan Rogers’ sublime, “MacDonnell on the Heights”: “Perhaps had you not fallen/ You might be what Brock became/ But not one in ten thousand knows your name.”

In sports too? Yup. The most beloved sports poem is still “Casey at the Bat,” ending: “But there is no joy in Mudville, mighty Casey has struck out.”

This is a complex, delightful, skittish topic. For athletes, winning is central. They have to win or, more realistically, be motivated by the need to. You can’t just treat it as a great, well-paid job. If you do, it’ll show. Ken Dryden once came to a class I taught on Canadian culture and was pressed so hard by students about his desire to win, that he backed up against the blackboard, saying “I don’t think I should need to apologize for that.”

For fans it’s different. What they need is hope.

I’ve shared season tickets to Maple Leafs games since 1973 and most of that time, including the Dryden (as hockey boss) era, there was hope. There were exceptions, like the Burke-Kessel era, when the fans grew surly. But fortunately, humans can survive on hope, since there’s more of it than victory.

The Scots gave a display of this at last month’s Euro Cup. “We never seem to do too well,” ran their song, and “Time will tell if we are gonna make it” — then a pause followed with brutal honesty by — “through the group stage, nobody’s saying we are gonna win it.” Then the music goes upbeat because humans live on hope, not wins, though it’s wins we hope for.

Many years ago, in pre-Thatcher England, some kids playing cricket in Battersea Park explained the game to me. Since the field was unmarked, it fell on fielders to say whether a ball landed in or out of bounds. I asked why they wouldn’t simply lie. They smiled with a hint of pity and said, “Oh that wouldn’t be spo’ting.”

Our games run deep, and they’re not only about winning.

This article was originally published in the Toronto Star.