The federal government never tires of boasting that Canada’s labour market has performed better than most other countries through the financial crisis and subsequent recession, and that the number of Canadians working today is greater than it was before the recession hit. That means we have fully recovered from the downturn, and the Tories are good economic managers, right? Wrong.

The whole trick is based on ignoring the fact that Canada’s population is growing, and relatively rapidly. Our working-age population has grown by 1.75 million since 2008 (or just under 1.5 per cent per year). So it’s hardly an accomplishment to get back to the same total absolute number of jobs (or even higher), when there are 1.75 million more Canadians capable of working.

The best way to measure jobs performance over time, relative to population growth, is by analyzing the employment rate. (It’s better than the unemployment rate, which is distorted by the problem of falling labour force participation, which in turn reflects large numbers of Canadians who’ve given up looking for work.) Canada’s pre-recession peak employment rate was 63.8 per cent (attained early in 2008). It plunged quickly and frighteningly, to 61.3 per cent by June 2009 — a decline of 2.5 points. Then it recovered, for a while — reaching 61.9 per cent by January 2011. With a few bumps along the road, that’s exactly where it sits today. The employment rate for June was 61.9 per cent. The labour market has recovered less than one-quarter (0.6 points out of a total decline of 2.5 points) of the damage that was done by the recession. More damningly, progress has stalled completely for the last two-and-a-half years — when governments (including ours) forgot about stimulus, and turned to austerity.

International comparisons are also skewed by this phony reasoning. Countries like Germany or Japan, with relatively stagnant populations, don’t need to create net new jobs in order to retain good labour market health. Canada does. So showing that Canada’s absolute job-creation rate is stronger than countries with low or even negative population growth, is a chump’s achievement.

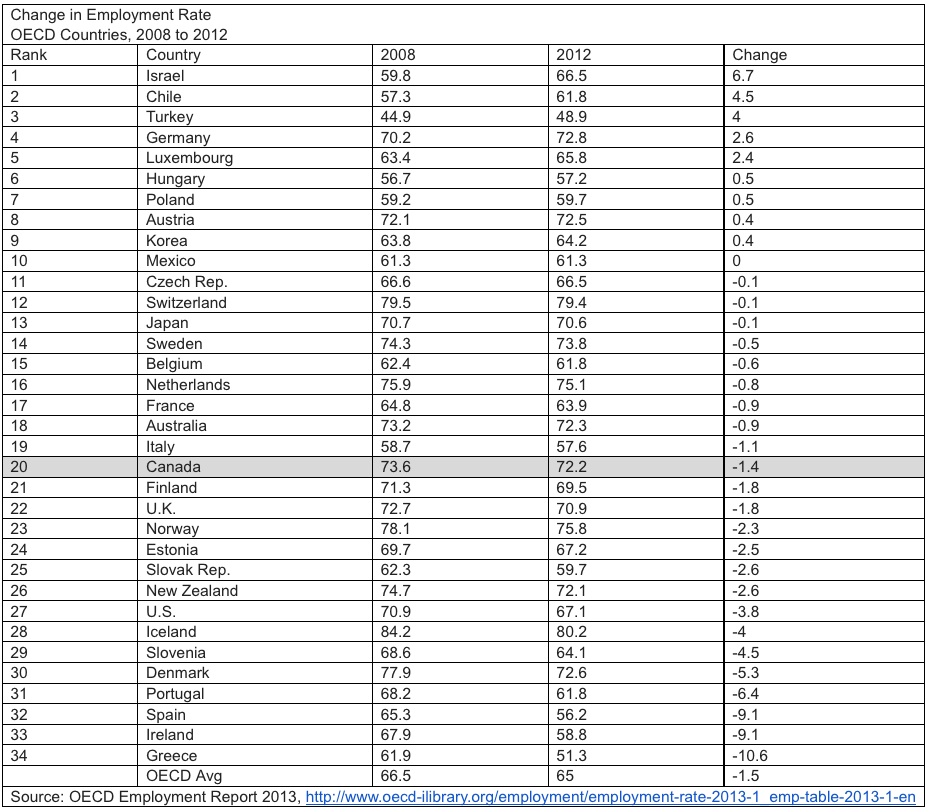

The OECD Employment Outlook released earlier this week had some surprisingly critical words to say about Canada’s notoriously weak employment protections (which it ranks as among the most employer-friendly in the world). Dig into its statistical tables, and you will also find some damning statistical data. Their table on the evolution of the employment rate in 34 OECD member countries puts paid to the Tory claim about our relatively strong jobs performance. When I last reviewed this data (for a CCPA report published in early 2012, titled Canada’s Incomplete and Mediocre Recovery, available at www.policyalternatives.ca) we ranked right at the mid-point. After another year of labour market non-recovery we’ve fallen well into the lower half of the list. Ranked by change in employment rate between 2008 (when the recession hit) and 2012, Canada ranks 20th out of 34. I have organized the chart by ranking; the original OECD data is available here.

Nine countries have increased their employment rate since 2008 (including Germany, Korea, and Austria). These countries can claim to have fully recovered from the recession (at least by this central measure of labour market well-being). Canada, however, clearly cannot. We’ve done better than the U.S., and much better than countries hit by economic catastrophe (largely the result of misplaced austerity), such as Greece or Ireland. But we now rank squarely in the lower half of OECD countries according to job-creation (relative to population growth).

(Note the OECD table uses the annual average employment rate, whereas my earlier discussion above uses seasonally-adjusted monthly data. That’s why the 1.4 point net decline in the OECD data is smaller than the 1.9 point net decline in the monthly data. The absolute level of the numbers also differs due to the OECD’s use of a different definition of working age population. But the direction of change is still clear.)

It is simply false to assert that Canada’s labour market has recovered from the recession, or that Canada’s labour market has done better than most other countries in surviving the recession. No matter how often this claim is uttered by government officials and reported uncritically by lazy journalists, it’s still simply false.

Jim Stanford is an economist with CAW.