Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a supporting member of rabble.ca.

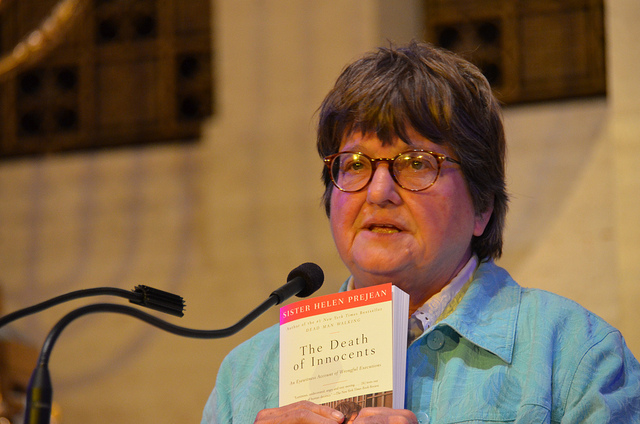

Thirty years ago, a Catholic nun working in a poor neighbourhood of New Orleans was asked if she would be a pen-pal to a death-row prisoner. Sister Helen Prejean agreed, forever changing her life, as well as the debate on capital punishment in this country.

Her experiences inspired her first book, Dead Man Walking: An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States, which has just been republished on its 20th anniversary. She was a pen pal with Patrick Sonnier, a convicted murderer on death row in Louisiana’s notorious Angola prison. In her distinctive Southern accent, she told me of her first visit to Sonnier: “It was scary as all get-out. I had never been in a prison before. … I was scared to meet him personally. When I saw his face, it was so human, it blew me away. I got a realization then, no matter what he had done … he is worth more than the worst thing he ever did. And the journey began from there.”

Sister Helen became Sonnier’s spiritual adviser, conversing with him as his execution approached. She spent his final hours with him, and witnessed his execution on April 5, 1984. She also was a spiritual adviser to another Angola death row prisoner, Robert Lee Willie, who was executed the same year. The book was made into a film, directed by Tim Robbins and starring Susan Sarandon as Prejean and Sean Penn as the character Matthew Poncelet, an amalgam of Sonnier and Williams. Sarandon won the Oscar for Best Actress, and the film’s success further intensified the national debate on the death penalty.

The United States is the only industrialized country in the world still using the death penalty. There are currently 3,125 people on death row in the U.S., although death-penalty opponents continue to make progress. Maryland is the most recent state to abolish capital punishment. After passage of the law, Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley wrote: “Evidence shows that the death penalty is not a deterrent, it cannot be administered without racial bias, and it costs three times as much as life in prison without parole. What’s more, there is no way to reverse a mistake if an innocent person is put to death.”

Studies of the racial bias abound. The Death Penalty Information Center, citing a recent Louisiana Law Review study, reports that in Louisiana, the odds of a death sentence were 97 per cent higher for crimes in which the victim was white than those where the victim was African-American. Nationally, 75 per cent of the cases that resulted in an execution had white victims.

Although Colorado is not one of the states to abolish the death penalty, Gov. John Hickenlooper used his executive authority to grant a temporary reprieve to one of the three death-row prisoners there, saying, “It is a legitimate question whether we as a state should be taking lives.”

This week, Indiana released a former death-row prisoner. Paula Cooper was convicted for the 1985 murder of Ruth Pelke. Cooper was sentenced to death at the age of 16, and was, at the time, the youngest person on death row in this country. Pelke’s grandson, Bill Pelke, actively campaigned for clemency for her: “I became convinced, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that my grandmother would have been appalled by the fact that this girl was on death row and there was so much hate and anger towards her.” He went on, “When Paula was taken off of death row in the fall of 1989, I thought, ‘Well, that’s it. She’s off of death row. My mission has been accomplished.'”

Nevertheless, Pelke joined a march from Florida’s death-row prison to Atlanta, on which he met Sister Helen Prejean. “After 17 days of walking down the highways with this nun, you get a real education about the death penalty. It was on that march with Sister Helen Prejean where I dedicated my life to the abolition of the death penalty,” he said. “As long as there’s any state in this world that’s killing their own citizens, I’m going to stand up and say that it’s wrong.”

Prejean said one of her greatest regrets was that she failed to reach out to the families of the murder victims while she was spiritual adviser to Sonnier and Willie. She went on to found Survive, an organization to support families of murder victims like Pelke. She wrapped up our conversation this week by saying: “I’ve accompanied six human beings and watched them be killed. I have a dedication to them to do this; I can’t walk away from this. I’m going to be doing this until I die.”

Denis Moynihan contributed research to this column.

Amy Goodman is the host of Democracy Now!, a daily international TV/radio news hour airing on more than 1,000 stations in North America. She is the co-author of The Silenced Majority, a New York Times best-seller.

Photo: Steve Rhodes/flickr