As events in Ferguson, New York, Oakland and beyond unfold, many Canadians have been quick to distance ourselves from the systemic racism that has plagued the U.S. since the times of the transatlantic slave trade. With most Canadian historical accounts selectively highlighting the Underground Railroad, we overlook the history of enslaved Black people within Canada, de facto prohibition on Black immigration from 1896-1915, displacement of communities from Africville and Hogan’s Alley, made-in-Canada segregation laws, foreign policy from Haiti to Somalia, and pervasive institutional and interpersonal anti-Black racism.

The problematic discourse of ‘Canada’s own Ferguson’

Over the past several months, dozens of (primarily white) commentators have noted that “Canada’s own Ferguson” is the violence inflicted on Indigenous people by Canadian police. Such analogies, particularly when made by those of us who are non-Black and non-Indigenous, are problematic.

Within a white supremacist society and ally industrial complex, such well-intentioned analogies ignore the multiplicities of racial histories and perpetuate both anti-Black racism and Indigenous genocide. It is commonplace to have U.S. media comparing Indigenous resurgence in Canada to Black civil rights movements in the U.S., conveniently ignoring Indigenous reclamations in their own backyard. Similarly, collapsing Black struggles in the U.S. into Indigenous struggles in Canada actively erases Black/Afrikan struggles in Canada.

It would be more appropriate to suggest that the Canadian corollary to Black struggles in the U.S. are specific Black-led struggles in our own country.

Theorist Scott Morgensen comments: “I am concerned that white people might embrace Indigenous solidarity in ways that evade our responsibilities to people of color and to their calls upon us to challenge all forms of white supremacy.”

This is not to minimize the centrality of Indigenous self-determination struggles or to suggest that Indigenous and Black struggles on Turtle Island are not interconnected. As Indigenous feminist Andrea Smith notes, “[S]ettler colonialism does not merely operate by racializing Native peoples, positioning them as racial minorities rather than as colonized nations, but also through domesticating Black struggle within the framework of anti-racist rather than anti-colonial struggle.” On these mutually reinforcing processes, she concludes, ” Thus, the colonialism that never happened — anti-Blackness — helps reinforce the colonialism that is settled — the genocide of Indigenous peoples.”

Black Lives Matter and Idle No More/Indigenous Nationhood Movement — and the solidarities between them — are relevant all over Turtle Island, not just in zones demarcated by state borders. In both the Canada and the U.S., members of Indigenous, Black/Afrikan/Caribbean, and BlackNDN communities are most likely to be shot and killed by the police, have high incarceration rates, and face deliberate impoverishment and neglect by state institutions. Children from these communities are most likely to be apprehended, and disproportionate numbers of women/trans/genderqueer/two-spirit people are missing or murdered.

Afro-futurist healer Danielle Stevens powerfully indicts this system: “How do I survive in a country that was built through the labour, exploitation, and extermination of my ancestors, that has always devalued my entire existence and is working overtime to actualize my death?”

Black Lives in Canada

“The project of articulating Canadian blackness is difficult not because of the small number of us trying to take the tentative steps towards writing it, but rather because of the ways in which so many of us are always preoccupied with elsewhere and seldom with here… The writing of blackness in Canada, then, might begin with a belief that something important happens here.”

– Rinaldo Walcott, Black Like Who? Writing Black Canada

In September of this year, 33-year-old Jermaine Carby was shot and killed by police at a traffic stop. Eyewitnesses saw Carby walking with his arms stretched out when police fired several fatal shots. Ajamu Nangwaya has compiled an overwhelming list of over 50 police killings in the African community. Year after year — for example in the shootings of Albert Moses and Tommy Anthony Barnett and Andrew Bramwell and Hugh Dawson — police officers have been cleared of any criminal wrongdoing.

In 2002, the Toronto Star uncovered a troubling trend on racial profiling by Toronto Police Services. Over a period of five years, statistics showed that for minor drug possession charges, Blacks were more likely to charged than whites. And of those who were arrested, Blacks were twice as likely to be held in jail than whites.

Ten years later the Toronto Star followed up with a story that revealed that little had changed. “While blacks make up 8.3 per cent of Toronto’s population, they accounted for 25 per cent of the [police] cards filled out between 2008 and mid-2011,” they reported. Based on freedom of information requests, the Toronto Star has also revealed that Black males aged 15-24 are stopped and documented 2.5 times more than white males the same age.

And when it comes to hate crimes, Black people are one of the primary targets. Last year, those who identified as Black reported 42 per cent of all race-based hate crimes.

Paralleling the explosion of Indigenous women and immigrant detainees behind bars, Black people are one of the fastest-growing prison populations. Canada’s federal correctional investigator Howard Sapers even launched an investigation into the 80 per cent increase (52 per cent increase proportionally) of Black prisoners in federal jails over the past decade. Sapers found that while representing 2.5 per cent of Canada’s population, 10 per cent of those in federal prisons are Black. He also found that Black prisoners are more likely to do time in maximum security and solitary confinement.

In a study on Canada’s racialized labour force, researchers Sheila Block and Grace-Edward Galabuzi found that those who identified as Black faced the second-highest unemployment rate of all racial categories and the third-lowest earnings. Statistics by the Canadian Association of Social Workers reveals how the racialization of poverty is compounded by the feminization of poverty. The average wage of Black women is 79 per cent of what Black men earn.

And finally, according to a recent report, over 40 per cent of apprehended youth placed into the Children’s Aid Society of Toronto system are Black youth, in particular those of Jamaican background. In one blatantly racist example, Children’s Aid was called because a teacher believed that a child eating roti was “not healthy.” This criminalization of Black mothering and Black families exists alongside the annihilation of Indigenous families through the child welfare system, our modern-day residential schools.

These statistics on institutional racism in Canada are the tip of the iceberg. Underneath are hundreds of stories of anti-Black racism — denial of service and employer discrimination, the simultaneous demonization and exotification of Black bodies, tokenization and shadeism, perceptions of Black/Afrikan cultural inferiority even as appropriation of Black cultural and feminist production continues, the social discipline of Black/Afrikan communities from schools to housing agencies, and the callous and colonial disregard of Black lives across the world imbued in military, health, and climate policy. And all of these forms of anti-Black racism, and more, also occur within our own social movements.

In a powerful femifesto, Alicia Garza has written that Black Lives Matter is an overarching “ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise.” And as a network of Black organizations highlights, “The truth is that justice eludes us: at our schools, in our streets, at our borders, in prison yards, on protest lines and even in our homes. It is that full freedom that we fight for when we say that #BlackLivesMatter.”

For those of us in Canada, it is too easy to point fingers south of the border. Our institutions, communities, and movements need to be accountable for our own anti-Black racism.

And in calling for this collective accountability, I include myself. I have not adequately prioritized allying with Black/Afrikan people or struggles. As a non-Black person of colour, I have to do more to hold my own communities accountable since we cannot fight a white supremacist society without fighting structural anti-Blackness. Social movements, including No One Is Illegal, have been named for perpetuating anti-Black racism. How are we being collectively responsible to these critiques? We need to humbly and honestly acknowledge that many of us who face and fight oppression are also often perpetuating oppression against Black community organizers — whether through gaslighting, silencing, appropriation, shadeism, homogenizing experiences, or more. How can we centre — rather than marginalize or tokenize — Black/Afrikan organizers in our movements?

As writer and activist Walidah Imarisha illuminates: “[W]hen we’re seeing black youth centered, when we’re seeing young black women centered in these struggles, we see an entirely different way of engaging… They’re the leaders who can show us how to build a different world.”

* Edited with thanks to a Black organizer for pointing out that this piece was not holding myself or movements I am part of accountable for anti-Black racism.

Harsha Walia (@HarshaWalia) is a South Asian activist and writer based in Vancouver, unceded Coast Salish Territories. She has been involved in grassroots migrant justice, feminist, anti-racist, Indigenous solidarity, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist movements for over a decade. She is the author of Undoing Border Imperialism (2013, 2014). The column, “Exception to the Rule,” is about challenging norms, carving space and centring the dispossessed.

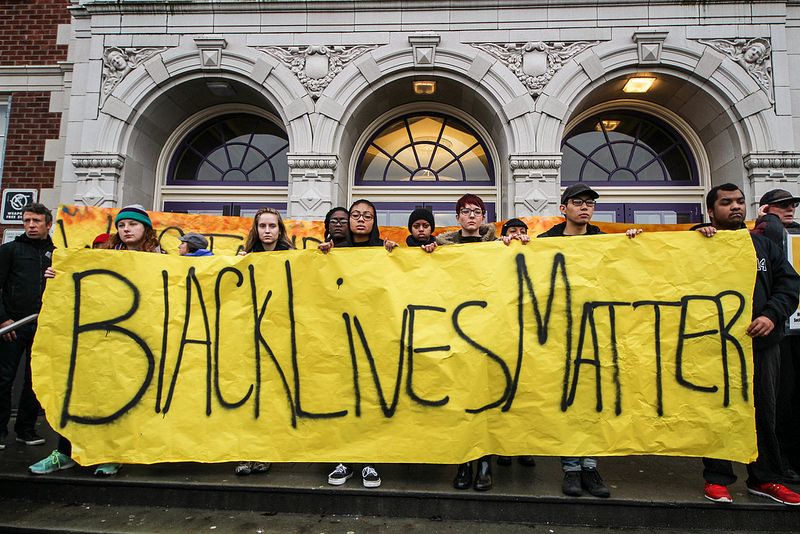

Photo: scottlum/flickr