Given the exhausting recent round of celebrating significant national anniversaries — Vimy’s 100th, Canada’s 150th — some Canadians may feel partied-out when family and friends gather again in a few months to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Canada’s income tax.

Of course, many will feel there’s nothing to celebrate. After decades of tax phobia, incited by business commentators and right-wing think-tanks like the Fraser Institute, some Canadians may well regard the 100th anniversary of the income tax — September 20 — as a day of infamy. The Fraser Institute is already planning to use the occasion to stir up fresh tax rage in the land.

That’s why it’s worth pointing out that, in any thoughtful assessment, the establishment of an income tax would be regarded as a nation-building event — ultimately as important as what was achieved on the battlefield at Vimy or the conference room in Charlottetown.

The income tax made it possible for Canada to develop into the advanced society that we are today, enabling us to raise the revenue to fight the Second World War and then create strong public programs in health care, education and social insurance that have pushed us toward the top of every global index of human development.

While the Fraser Institute crowd always tries to convince us we can’t afford the things we want, we actually can — thanks to the income tax.

Individually, we may struggle to provide for our needs, but when we pool our resources, we’re fabulously rich. This explains why collectively we can create an excellent public health-care system for all, while the U.S., abandoning its citizens to the marketplace, ends up with a far more costly system that leaves tens of millions uninsured.

In addition to raising revenue, the income tax is designed to ensure the burden of supporting government is shared fairly among citizens. So, unlike other taxes, its rates are “progressive” — imposing a heavier burden on those with bigger incomes.

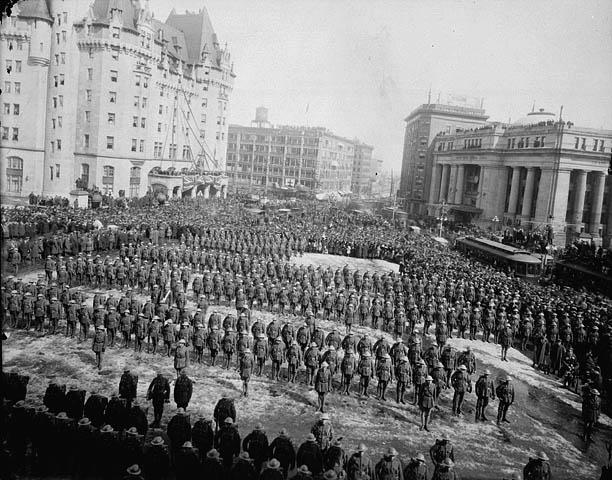

Its role as a “make-the-rich-pay” tax goes all the way back to the beginning. Pressure for the tax arose among working people who were risking their lives in the trenches of the First World War, while back home Canada’s elite grew wildly rich in the revved-up war economy. As the Conservative government considered imposing conscription, a rallying cry arose from labour and farm organizations: “No conscription of men without conscription of wealth!”

The day after Parliament passed the contentious conscription bill, the government announced plans for an income tax.

In recent decades, however, the Fraser Institute and much of the business community have conducted a relentless — and fairly successful — campaign aimed at vilifying taxes in general, and taxes on the rich in particular.

They’ve succeeded in whittling down the progressivity in the income tax. In 1966, the top marginal rate was 80 per cent on income above $400,000 ($3 million in today’s dollars). Today, the top rate (which varies between provinces) is typically just above 50 per cent.

They’ve also won deep cuts to corporate taxes and taxes on capital. Along with sales tax reductions, these cuts have left a gaping hole in government finances.

If Canadian governments (at all levels) collected the same percentage of tax as they did in 2000, they would have had an additional $78 billion in revenue every year — enough to fund new programs like national childcare and pharmacare.

Instead, we watch as health care, education and other vital programs face ever more cuts, leaving us believing the narrative that government must partner with the private sector if we want these services — even though that will ultimately drive up costs.

Canadian politicians have largely capitulated to the anti-tax demands of the business elite, apparently fearful of threats that otherwise the rich will leave the country.

Such threats will no doubt continue.

A better response to them may be the one delivered many years ago by William Jennings Bryan, the fiery American Populist Party leader in the 1890s, when populists truly championed the people.

In an impassioned 1894 speech that’s worth recalling as we celebrate our income tax’s centennial, Bryan urged the U.S. Congress not to be intimidated by the hundreds of wealthy Americans who signed a petition threatening to leave the country if an income tax were introduced:

“We can better afford to lose them and their fortunes than risk the contaminating influence of their presence,” he roared. “Let them depart! And as they leave without regret the land of their birth, let them go with the poet’s curse ringing in their ears!”

Linda McQuaig is a journalist and author. Her book Shooting the Hippo: Death by Deficit and Other Canadian Myths was among the books selected by the Literary Review of Canada as the “25 most influential Canadian books of the past 25 years.” This column originally appeared in the Toronto Star.

Photo: Library and Archives Canada, PA-099796 /flickr

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism.