Two Conference of the Parties (COPs) are following each other this fall – the climate change COP 27 last month in Egypt and the biodiversity COP 15 this month in Montreal. These global environmental summits have been held for nearly 30 years, following the signing of climate change and biodiversity treaties at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

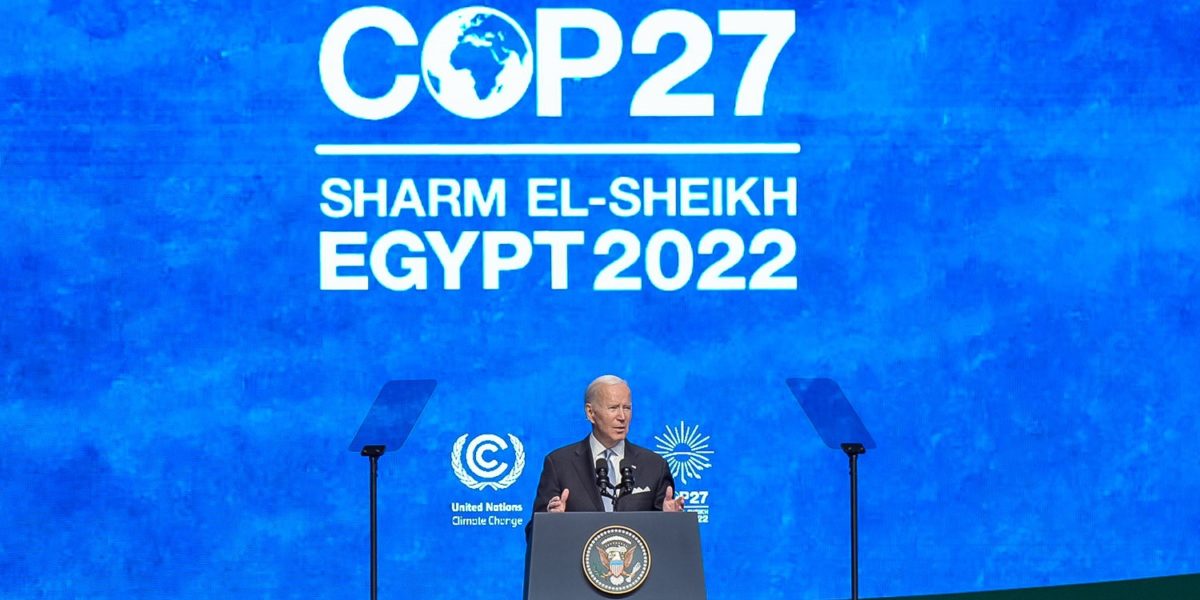

COP 27 was a bad COP. Hundreds of oil and gas lobbyists flew to a Red Sea resort to block effective action to slow the extraction and burning of fossil fuels. They succeeded, increasing the likelihood that billions of residents of planet Earth will experience extreme weather events and climate-induced ecosystem collapse in their lifetime.

Writing in the Guardian, Bill McGuire called the climate COP “a bloated travelling circus that sets up once a year, and from which little but words ever emerge.” In the Globe and Mail, Eric Reguly said “Today’s carnivalesque events have proven expensive, climate unfriendly, chaotic, stressful – and largely useless… Time to kill them off.”

Can the biodiversity COP 15 be a good COP?

For this to happen, governments must follow both western science and traditional knowledge. Many people have heard of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN body created in 1988 to assess the science related to climate change. Although the IPCC received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007, its repeated warnings about the costs of climate inaction have been ignored.

Few people are aware that a non-UN biodiversity equivalent to the IPCC was created in 2012, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

IPBES says that the time for incremental measures to address the twin climate and biodiversity crises is past. IPBES scientists are working on a transformative change assessment that will be released in 2023.

Political leaders included the concept of transformative change in the Kunming Declaration adopted at part 1 of COP 15, held last October in China. The Declaration says that “urgent and integrated action is needed, for transformative change, across all sectors of the economy and all parts of society.”

To understand integrated action and transformative change, think of a forest. Think of the electrically sensitive network of fungal hyphae linking trees together, exchanging energy and nutrients with them. Fungi are waste management heroes, transforming discarded roots, branches and leaves, making them available for a new generation.

Now consider the current reality. To grow crops and expand urban settlements, we kill fungi (fungicide), plants (herbicide), insects (insecticide), and ultimately Mother Earth (matricide). Gas-powered death machines hasten extinction. Bad COPs make sure there’s plenty of fuel to keep them going.

Biodiversity scientists speak of “habitat loss” – a polite term. Our feathered, furry and fishy friends must lose their homes so we can have our own. But if we keep slicing bits off Mother Earth, she won’t be able to continue to feed and nurture us, her children. We’re all connected in one big web of life.

Think of Ontario. Developers give a provincial premier a few hundred thousand in campaign donations, buying new laws and policies. Clear the fields and forests. Drain the wetlands. Build houses and roads.

Money is a drug. It’s addictive. Politicians and developers feed incestuously off each other. Economic growth trumps rational behavior. We’re a civilization of drug dealers. Negotiate. Make the deal.

Speaking of negotiations, COPs are all about removing brackets and producing a clean text. There could be a bit of drama at COP 15 over whether to keep Mother Earth in the first paragraph of the Global Biodiversity Framework – biodiversity’s equivalent of the Paris climate accord. Here’s how it reads at present:

Biodiversity is fundamental to human well-being and a healthy planet [for peoples living in harmony with nature and Mother Earth.] It underpins virtually every part of our lives]; we depend on it for food, medicine, energy, clean air and water, security from natural disasters as well as recreation and cultural inspiration, [and supports all systems of life on earth], among others.

Mother Earth is in brackets. Will they come off, or will she be deleted?

Indigenous peoples will be speaking up for Mother Earth at COP 15. Here’s how the Assembly of First Nations puts it in Honouring Earth:

First Nations peoples have a special relationship with the earth and all living things in it. This relationship is based on a profound spiritual connection to Mother Earth that guided indigenous peoples to practice reverence, humility and reciprocity.

There’s more. Read it. Western science and traditional knowledge can work together. Transformative change plus a spiritual connection to Mother Earth can save us.