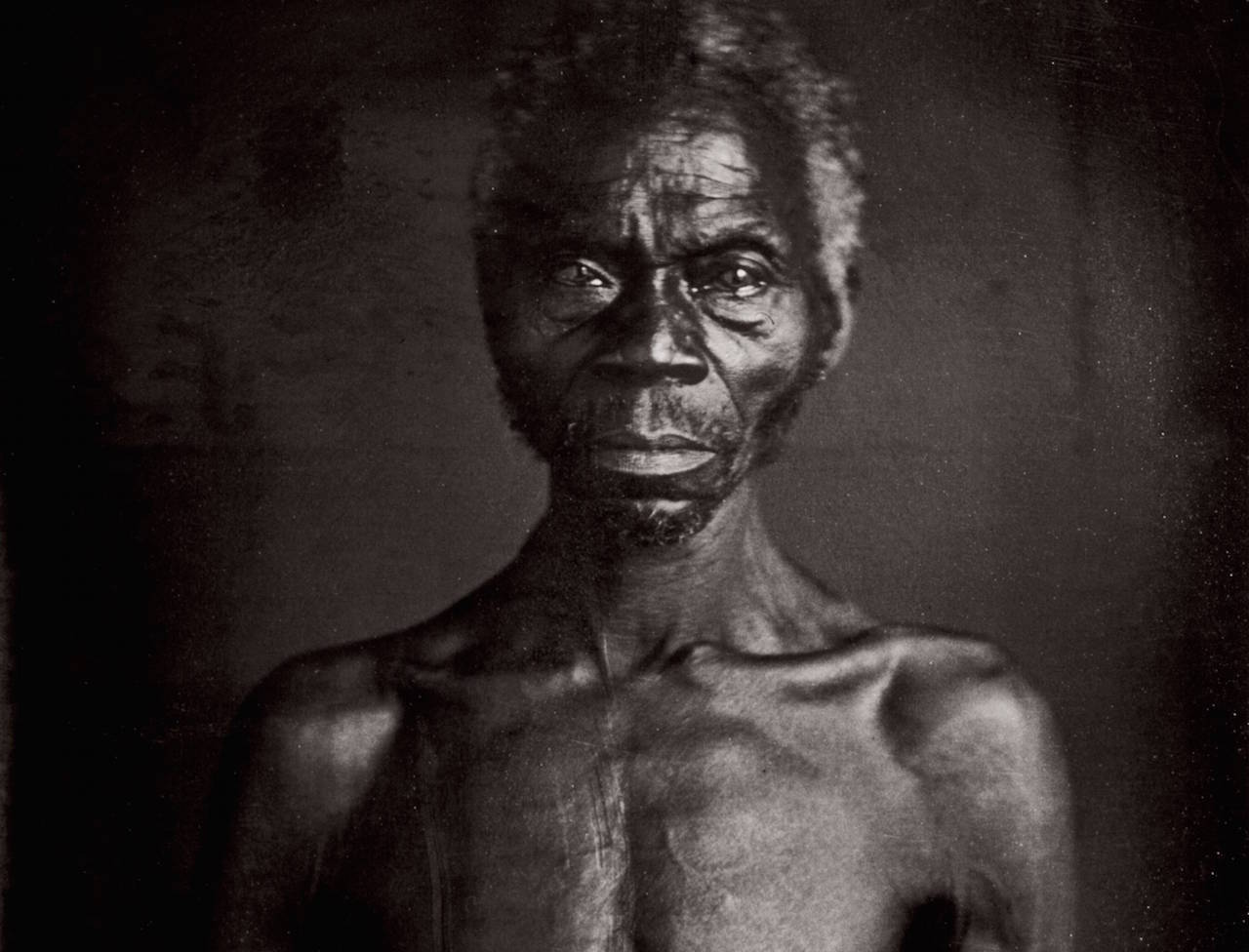

The haunting gaze of Papa Renty peers from the 1850 daguerreotype. The enslaved man was forced to pose, naked, for a study being conducted by a racist Harvard anthropologist named Louis Agassiz. The Swiss-born scientist promoted “polygenism,” a theory that held that different races were separate species, and that the white race was far superior to the Black race. To validate this, Agassiz traveled from Harvard to South Carolina seeking authentic, “pure” Black slaves, those whose original, African racial makeup hadn’t been diluted, as all too often occurred, by the rape of slave women by their white masters. Agassiz commissioned these images of Renty, his daughter Delia and other slaves, and returned to Harvard. The images eventually ended up in a storage cabinet, forgotten, until they were discovered in 1976. Since then, Harvard has kept tight control over access to the collection, charging licensing fees to any seeking to use them. Now, Tamara Lanier, one of Renty’s direct descendants, is suing Harvard, demanding that the daguerreotypes of Renty and Delia be returned to the family.

“When will Harvard University finally free Renty?” Lanier’s lawyer, civil-rights attorney Benjamin Crump, asked on the Democracy Now! news hour. “These daguerreotypes are very, very valuable. They are the earliest known photographs of American slaves and some of the earliest known photographs in America,” adding that they are “priceless to Tamara Lanier and her family, because they’re the linear descendants. … But Harvard is telling Ms. Lanier and her family: ‘No, no, Renty still belongs to us. He’s still our property.'”

Ownership of the daguerreotypes is a legal question that strikes at the heart of slavery, its history in building not only the United States but also institutions like Harvard, and what our society owes to descendants of slaves. “Make no mistake about it,” Crump said. The lawsuit “is landmark in its scope, because it will be the first time that descendants of African slaves in America have been compensated in any way, fashion or form from an American institution.” He says it could be as important as Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court case that desegregated schools nationally.

The riveting, 24-page complaint opens with a quote from Maya Angelou, also a descendant of slaves: “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage need not be lived again.” The lawsuit details Louis Agassiz’s racist theories and his meteoric rise in U.S. academic and elite circles. It recounts how his research describing the inferiority of Blacks was funded by a Boston textile magnate whose business depended on a steady supply of cheap cotton from Southern slave plantations.

It also describes what is known of Papa Renty. A native of Congo, Renty somehow obtained a copy of Noah Webster’s Blue Back Speller, and managed to teach himself, and others, to read — a crime for slaves. It’s the same book legendary abolitionist Frederick Douglass used when learning to read and write while still enslaved, working in Baltimore’s shipyards. Papa Renty’s son and grandson were also named Renty. They were forced to use the surname of their owner, Taylor. Renty Taylor III was sold to a slave owner named Thompson. Among his children was Frederick Douglass Thompson, Tamara Lanier’s grandfather.

“As a child, my mom often talked about her enslaved ancestors, particularly the man in the image, who she fondly referred to as Papa Renty,” Lanier said on Democracy Now! “She also talked about our lineage, how our family was broken apart by slavery.”

Along with Renty, and Delia, Harvard’s collection has images of other slaves, taken in the same Columbia, South Carolina, portrait studio. They are mugshot style, one image head-on, another from the side. Also from Taylor’s plantation is Jack, a native of Guinea, and his daughter, Drana. Drana, like Delia, is stripped to the waist, like the men. From the plantation of a Col. Wade Hamilton, also near Columbia, is a male named Fassena, a carpenter and slave.

Tamara Lanier hopes the images will expand the national dialogue on slavery. “It’s important for me that people know who Renty was and who Agassiz was,” she said. “I hope that there is a greater education or a reteaching of history, so that we can dispute the legacy that Agassiz has stained my family with.”

While her lawsuit proceeds, the images of Renty and the others remain at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, bearing the copyright, “President and Fellows of Harvard College.” On this, the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first slave ship to the shores of North America, it is high time for Harvard to give up its claimed copyright and just do what’s right, reuniting Renty and Delia with their descendants.

Amy Goodman is the host of Democracy Now!, a daily international TV/radio news hour airing on more than 1,300 stations. She is the co-author, with Denis Moynihan, of The Silenced Majority, a New York Times bestseller. This column originally appeared on Truthdig.

Photo: Joseph Thomas Zealy/Harvard University/Wikimedia Commons

Help make rabble sustainable. Please consider supporting our work with a monthly donation. Support rabble.ca today for as little as $1 per month!