Canadian writer Ian Adams died Sunday of a stroke at 84. He was unique. As a journalist, novelist and screenwriter, he didn’t just cover, he confronted subjects like the Cold War’s sordidness and the travesty of residential schools. There was no one like him.

He was born to crazy missionary parents (his term) in 1937 in the Belgian Congo when it was still called that. They abandoned him to orphanhood (his terms) in boarding schools when the war came. Eventually he made his way to Winnipeg and worked in journalism, starting in the darkroom. By the 1960s he was writing for Maclean’s magazine — a mighty media force then. In northern Ontario he came upon the story of an Indigenous boy named Chanie “Charlie” Wenjack who ran away from a residential school and died trying to get home.

He wrote a cover story in 1967, against a background of “media silence” about those institutions. Maclean’s ran it but disapproved. Forty-five years later, Gord Downie of the Tragically Hip made an album about Chanie one of his final projects, inspired by Ian’s article. When he performed it at Massey Hall in 2016, he brought Ian onstage to a standing ovation.

Ian straddled a time when no journalists went to university or J-school and one now when everyone does, but he left journalism to write fiction, on similar subjects. That liberated him. He said writing novels let you use all your resources and delve in ways that journalism’s prim, limiting procedures didn’t.

He wanted less to explore what actually happened, which is often hard to ever verify with certainty — think of the Kennedy assassination — than what lay behind it and could’ve happened. He got into journalism because he wanted to reveal the truth, and he got out of it and into fiction for the same reason.

His recurring subject became the world of security services and spies, run in Canada then by the RCMP. He was fascinated with spies as outlaws, beyond society’s control. When he unearthed a scandal (as he often did: he’d drink night after night with a source just to reach the point where he could pop a crucial question), he might just pass it on to a journalist. That sometimes led to upheavals, like security moving from RCMP jurisdiction to a new agency, CSIS. Other strands became the basis of his novels.

One was S: Portrait of a Spy, about a triple agent in the RCMP, working for Canada, the Soviets and the U.S. That was really all you needed to know about Canada’s humiliating role in the Cold War. It became the novel that was sued for libel; the plaintiff claimed he was the model for the protagonist. Ian called him “The Man Who Wanted to Be S.” The publisher withdrew the book. Writers set up an Ian Adams Defence Fund, the suit was settled, the book reappeared.

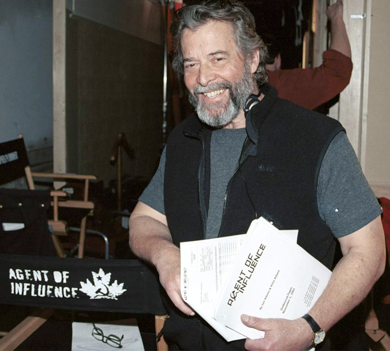

He developed a style largely his own for these novels, some of which became films. He’d occasionally rewrite a chapter in conventional thriller style just to show people like me, he said, that he could do it. We wrote a stage version of S together. When it opened in Ottawa, the cabinet minister in charge of the RCMP surprisingly accepted our invitation, though his equivalent onstage was portrayed as a fool. We knew he knew that because a plainclothes Mountie-type attended a preview and aimed his attaché case at the stage. It felt quite… Canadian.

Ian also wrote film scripts, often with his son Riley, a screenwriter, some based on Ian’s novels. Christopher Plummer played in one and Michael Moriarty, the fine actor who starred in the first version of Law & Order, in another. He developed severe hearing problems in recent years, a special affliction for someone who listened so well, and heard things — in large social aggregates and in individuals — that other Canadian writers couldn’t hear.

So he narrowed his focus to those nearest: Riley, granddaughter Poppy, his son from his first marriage, Shane, Shane’s son, Polaris. He wrote till the end.

He never wrote about his early years in the African heart of imperialism, or on the shores of the Indian Ocean. Perhaps it felt too piercing. But when he saw the corpse of Chanie Wenjack, described in a local article as simply “an Indian kid found dead near the tracks,” it surely echoed his own “orphanhood.” None of his writing was done to wrap fish with the next day, and be forgotten after that.

This column originally appeared in the Toronto Star.