Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

I’ve been reading about the great public debate on the theory of relativity. It happened 100 years ago, mostly in Europe, but it’s refreshing to look back at it in view of how today’s major science issue, climate change, has been treated — when it’s been treated — during the U.S. election.

For instance, by 1922, when the key confrontation occurred in Paris, between Einstein and French philosopher Henri Bergson, the basic position — relativity — was accepted by both scientists and the broad public. The debate was about significant details and implications, including policy matters.

By contrast, in the U.S. election, they’re still stuck in what’s essentially an up-or-down vote. Bernie Sanders, in his characteristic way, says, The debate is ovuh. Donald Trump, the Bernie inversion, calls it a hoax invented by China.

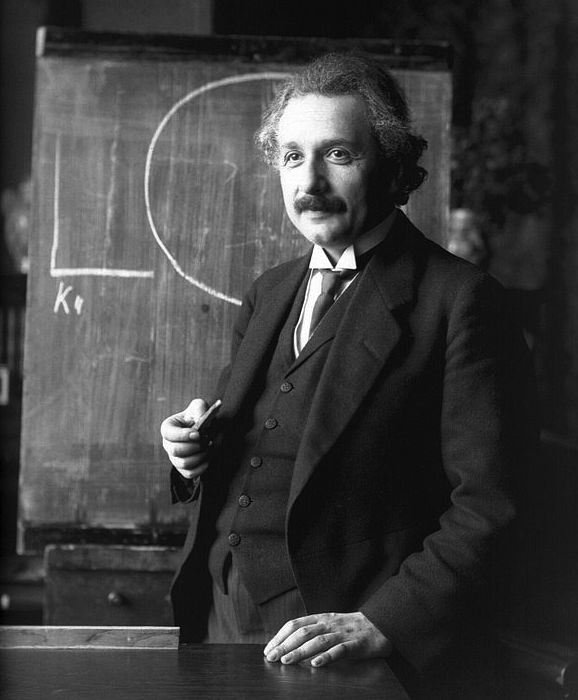

Back then, Einstein was already a global celebrity. Bergson, whose star has since faded, was roughly his equal. I happened to encounter his books in my first university year. My philosophy prof was a “Bergsonian.” He admired Bergson’s critique of Darwin in the name of “creative evolution” and the “élan vital,” or vital force, that powers life’s flow. Bergson’s argument on that hasn’t aged well but it was exhilarating to an undergrad. During grad studies in New York, my department of phenomenologists revered Bergson as their precursor. Both men had the ability to fill halls and even arenas. People battled for tickets.

Einstein’s decision to attend that Paris debate was complex, given fraught French-German relations after the First World War. As a German Jewish pacifist, he’d opposed the war but in the aftermath, felt Germany was being screwed by the victorious French. They’d just taken over the Ruhr industrial region. Bergson headed the League of Nations Committee for Intellectual Cooperation, to which he desperately wanted to recruit Einstein. Einstein though, sensed anti-Semitism or anti-Germanism in much of the opposition to his views, theoretical or political. He dithered awhile about the committee, then opted out.

On the practical level, there was an urgent need to standardize times and measures for the sake of technical efficiency and political harmony — and Einstein’s thing was definitely time-space. So concrete policies were at stake.

What did their basic conflict hinge on? The nature of reality, and the place of science. Einstein felt his representation of the world reflected it objectively: everything was already laid out imperturbably, in the time-space continuum. Bergson invoked a creative, unpredictable element. Reality was still unfolding; it didn’t pre-exist, it emerged. This was “time’s arrow”; Einstein called that illusory.

It sounds like a scientist-humanist dualism: Einsteinian “clock time” versus Bergsonian “lived time.” But there were wheels within wheels. Einstein, the relativist, was simultaneously seen as a “monist,” who conceptualized reality as an unchanging “block”– yet he was also an antiwar activist and Zionist. Bergson, passionate advocate of creativity and freedom, was allied, among others, with existentialist Martin Heidegger, who became a Nazi in the 1930s. There was a murky underside to his voluntarist sheen. Each position had implications for action, but nothing was utterly clear. So the debates and analyses raged.

The conflicts, implications — and personal agendas — persisted for decades. Jimena Canales, author of The Physicist and the Philosopher, sets them out.

The key issue then was the nature of time, apprehended through physics. The crucial nexus now is the environment and climate science. I’m resisting one-to-one parallels, but it’s hard not to be impressed by their discussion then.

By contrast I keep thinking about TV ads during this U.S. election that seem vaguely, furtively related to climate change, with people saying, “I’m an energy voter.” What is that? If it’s about climate, why not come out with it? Those energy voters look suburban, irritating and smug. If I was an American I might register as a low energy voter, or a clean energy voter, just to irk them. But where’s the debate? Where are the issues? And why don’t we see scientists and philosophers more prominently on the public stage?

I came of age, philosophically, in the existentialism era. Rationalism and science seemed dull, musty and inert, compared to dramatic existential leaps into the maelstroms, like politics. But the current U.S. parody of discussion has rehabbed, at least for me, the enlightenment ideal of rational discussion among people of good will and open minds. The Age of Reason never looked so good.

This column was first published in the Toronto Star.

Photo: Ferdinand Schmutzer/Wikimedia Commons

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.