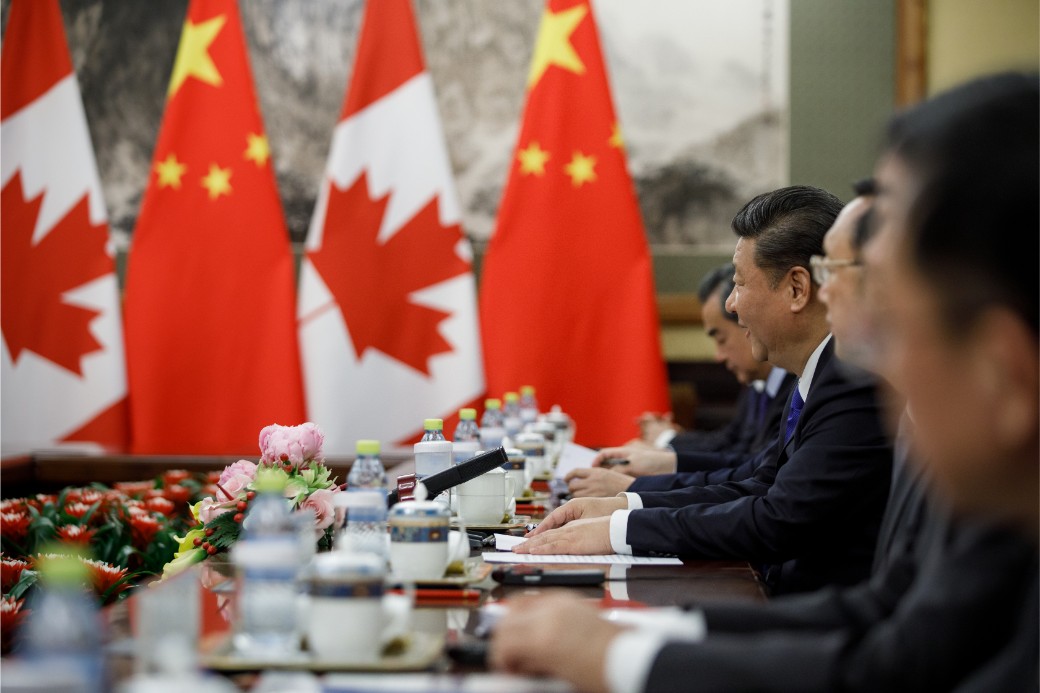

Politics is often a source of great ironies working themselves out over times, places and personalities. At the moment there is much irony to be found in the crisis in Canada-China relations — precipitated by the arrest and detainment of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver, and the apparently retaliatory detainment of Canadians Michel Spavor and Michael Kovrig, and arbitrary increase of a 15-year prison term to a death sentence for Canadian Robert Schellenberg in China.

The irony is that it’s the China-friendly Liberals who find themselves in this mess and who are hopefully going to learn something from the mess. Liberal governments have for some time displayed a frustrating mixture of realpolitik, naivete, willful blindness, obsequiousness, and Western liberal democratic arrogance when it comes to China. The realpolitik began with Pierre Trudeau’s appropriate recognition of “Red China” in 1970.

The lesson to be learned, as Jonathan Manthorpe argues in his recent book, The Claws of the Panda, is that Canada needs a China policy that is “less self-delusional, more courageous, and more intelligent.” Not engaging China is not an option. Stephen Harper tried that, and ended up doing photo-ops with pandas.

Some weeks ago there was debate about whether it was appropriate for a Canadian delegation of MPs and senators to visit China under the auspices of the Canada-China Legislative Association, especially given that a Canadian ministerial visit had just been cancelled.

The formation of this group provides an interesting case study in Canada-China relations. In the late 1990s, then prime minister Jean Chrétien was told by the Chinese that they were no longer happy with just having a Canada-China Friendship Group. China wanted parity with the United States. They wanted a full-fledged Canada-China Parliamentary Association, modelled on the longstanding Canada-U.S. Parliamentary Association.

The order went down from Chrétien that such an association should be created. As NDP House Leader at the time, I was invited to an initial meeting at which this was presented as a fait accompli, name and all. When I objected to the idea on the basis that there wasn’t anything in China that could properly be called a parliament, with no opposition, no elections, and that it was a one-party state, the objection was greeted with both anger and astonishment. Why be so difficult? How could Canada say no to such a fountain of potential future investment, and wouldn’t the Chinese be insulted beyond measure?

Sometime after the first meeting, which ended inconclusively, Minister of International Trade Sergio Marchi announced, while in China, that such a group would be formed. This led to a Reform Party point of privilege. The complaint was that the decision had been announced by a minister before Parliament had actually approved it. In the ensuing debate, only the NDP argued that questions should also be asked about the name of the association. More meetings were held. In the end I suggested asking the Chinese if they would settle for something called the Canada-China Legislative Association. After all, the People’s Congress does legislate, even if it is not comparable to a parliament. The reply to this was that the Chinese would never agree.

At the time I had been reading former Governor of Hong Kong Chris Patten, concerning the negotiations he had with China. His view was that one might be surprised at the outcome of standing one’s ground on some issues. With this in mind, I encouraged the Liberals in charge of the process to at least give the proposal a try. To this day, the group is called the Canada-China Legislative Association.

The lesson, if there is one, is that in negotiations the Chinese sometimes look for, or accept, solutions to difficult problems that — it is initially thought — they might never entertain. Let’s hope that there is something like this as the current crisis proceeds. In the meantime, the Liberals continue to be caught between their former attitude towards China and their current focus on not being on the wrong side of the U.S.

Around the same time as the Canada-China Legislative Association was formed, there was an ongoing debate about China’s admission to the World Trade Organization (WTO), which eventually happened in December 2001. The NDP saw the admission, with China’s record on human rights and labour rights, as something that would worsen the already uneven playing field that workers in Canada and other democracies with strong unions and decent wages face.

Liberals were full of assurances that the more Canada traded with China, the more they would become like us, and that we all needed to be patient and understanding. It didn’t seem to occur to them that we might instead become more like them, by further aggravating the race to the bottom that is characteristic of corporate globalization. It was a complicated self-deceiving Western arrogance, an arguably re-colonizing attitude mixed with salivation at the prospect of accessing China as a place to do business.

When China was a place where Western capitalists could not make money by taking advantage of cheap labour, it was an affront to Western values. When money was to be made, it was a different story.

Bill Blaikie, former MP and MLA, writes on Canadian politics, political parties, and Parliament.

Photo: Adam Scotti/PMO

Help make rabble sustainable. Please consider supporting our work with a monthly donation. Support rabble.ca today for as little as $1 per month!