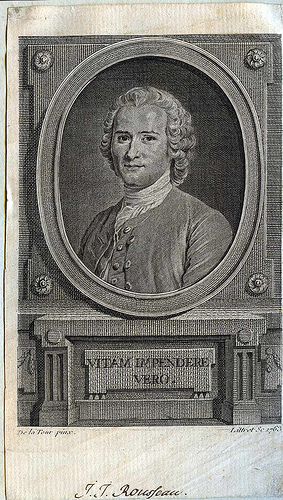

On the cover of its special edition magazine commemorating the 300th anniversary of the birth of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (June 28, 1712), Le Monde designates him as “the Subversive.” True enough, Rousseau was a contestataire, a non-conformist, a rebel, a pre-revolutionary, whose remains were carried to the Pantheon in the aftermath of the French Revolution, to be buried a hero.

Rousseau shall forever be known for championing liberty. Famously, for Rousseau, individuals are born and remain free, and enjoy equal rights. Society corrupted the individual, but all was not lost. Through building a “culture,” individuals could transform social life and live in accordance with nature.

The intellectual historian Peter Gay in The Party of Humanity, his essay collection treating the French Enlightenment, refers to Rousseau as the theorist of democratic movements. Certainly the life and work of Rousseau would resonate today with equality-seeking groups, ecologists, social reformers, and those looking to overthrow an unjust political order. Indeed it is hard to imagine any thinker who raised themes more relevant to radical left politics of today than Rousseau.

A Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (1755) could have been the founding text of the Occupy movement. In this work, Rousseau identified the ownership of private property as being the source of injustice.

In The Social Contract (1762), Rousseau examined the universal, what he called the general interest, or the common good, which was more than simply the addition of individual choices or aspirations, not to be confused with the will of the majority. Guy LaFrance, the Canadian philosopher, showed how Rousseau looked to ancient philosophy to ground his theory of law as being about humanity, not commerce and property; about democratic rights, not institutions.

Rousseau asked Who am I? And answered: my heart, which ensures the goodness inherent in the individual life. What is needed to reform society is to cultivate individual autonomy, or consciousness. This could be done by calling upon reason, but passion, the emotions and appetites needed to be integrated as well.

In 18th-century Germany, Kant recognized the philosophical genius of Rousseau, and was greatly inspired by him. Rousseau rejected the “rationalist” outlook of the French philosophes such as Diderot, and especially the creed that nature could be mastered, dominated and controlled. For Rousseau the natural world needed first to be known and respected, a view that resonates strongly today.

Rousseau was a native of Geneva and the city is hosting celebrations of the anniversary of his birth this year. But, in his lifetime Rousseau was persecuted, attacked, and his works, notably Emile — about how children could be self-educated — were burned in Paris, Geneva and Holland. Today thought to be one of the greatest thinkers of all time, Rousseau has always had his detractors. Voltaire, the great philosopher of the Enlightenment (whose books were also burned) was an early adversary. In France, Rousseau was celebrated as a literary figure above all, until the 20th century. During the Cold War, Anglo-American writers tried to tie Rousseau to authoritarian political practices.

Rousseau lived most of his life as an itinerant. His mother died after giving him birth. When he was 10 his father was forced to flee Geneva, and left him to the care of a pastor. He came to France at age 16, where he died in 1778. A composer and theorist of music, his attachment to harmony extended to the world. A great believer in transparency of thought, as he became celebrated for his uncompromising views, he was forced to flee France for Switzerland, and then to England for year.

Julia Kristeva, the eminent French intellectual, in her portrait of Rousseau for Le Monde’s anniversary magazine writes about him as the best-selling author of the 18th century. His novel Julie or the New Heloise (1761) sold out everywhere, and people paid to borrow the book, by the day or by the hour.

Rousseau is widely read and studied today, 300 years after his birth, because his insight into the human condition goes beyond the skepticism of thinkers determined to overcome the authority of religion or ideology. A social critic, he embraces a dialogue with the inner self. Not for Rousseau, off-the-shelf academic empiricism.

In his politics, the standard account is that he tried, and failed, to accommodate both individual freedom and the authority of the state. But Rousseau looked to a society of free, educated people, a society populated by individuals like his literary creation Emile, to recognize what was best for all — the common good. For Rousseau, politics, living with others, was a moral undertaking. Forever a solitary thinker, Rousseau embraced solidarity with his fellow human beings.

Duncan Cameron is the president of rabble.ca and writes a weekly column on politics and current affairs.

Image: Skara kommun/Flickr