My copy of the Globe and Mail the other day included the July edition of the Report on Business magazine, featuring its annual ranking of the top 1000 publicly-traded corporations in Canada. The survey makes for fascinating reading. In honour of Canada Day, I would like to present a few statistical factoids about these huge institutions that determine the direction of our economy, and increasingly our politics and our society. This profile provides some fascinating insights about the changing structure of corporate Canada, and the corresponding evolution of Canada.

I zero in on the biggest of the big: the 50 most profitable public corporations in Canada in 2010, according to the rankings. These 50 companies raked in $80 billion worth of after-tax net income. In contrast, the remaining 950 companies on the RoB list received only $20 billion more. So by focusing on the top 50, we are certainly catching most of the action.

Indeed, those 50 giant companies accounted for about two-thirds of the after-tax profits generated by all corporations (public or otherwise, foreign or Canadian) in Canada in 2010. According to Statistics Canada data, total before-tax corporate profits last year equalled some $180 billion, $55 billion (or 30 per cent) of which was paid back in direct taxes to all levels of government, leaving some $125 billion worth of net income. Almost two-thirds of that was captured by the top 50 corporations.

2010 was a much better year for corporate Canada. Before-tax corporate profits in Canada jumped by over 20 per cent in 2010 — rebounding from crisis-ridden 2009. After-tax profits jumped by over 30 per cent (taxes grew less than before-tax profits partly because of corporate tax cuts, and partly because of timing issues related to the business cycle). The top 50, however, did even better than that: their total after-tax profits grew 40 per cent in the year. Just 9 of the 50 experienced a profit decline last year. The 17 resource companies on the list led the way: their after-tax profits grew by 70 per cent.

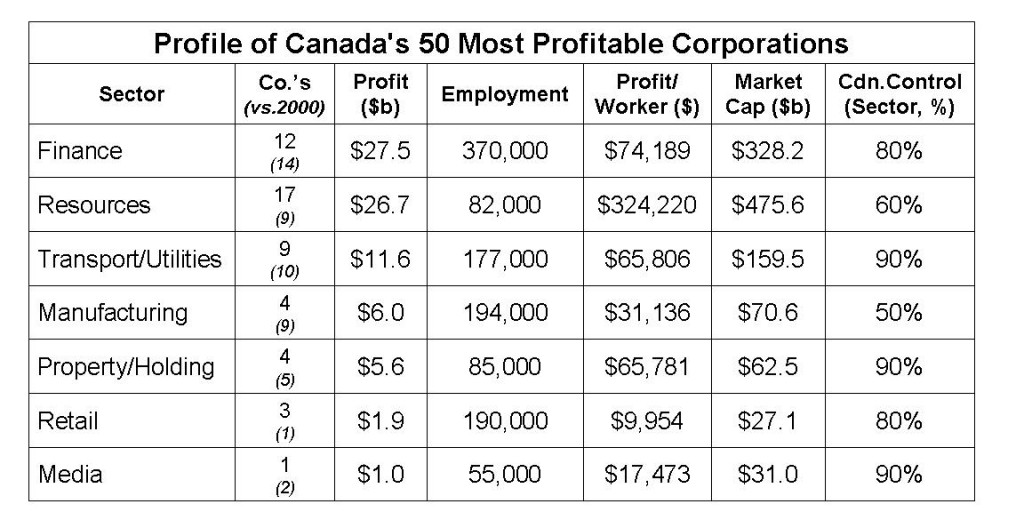

Reflecting the stunted structure of Canada’s private sector, the corporate top 50 listing is dominated by two sectors: finance (12 companies) and resource companies (17). These sectors took home over $25 billion each in after-tax profit (and together accounted for over two-thirds of the total profits of the top 50). While the leading role of big finance in corporate Canada has been fairly stable over time (there were 14 financial firms among the RoB’s top 50 a decade ago), the global commodities boom and Canada’s accelerating resource-dependence has almost doubled the number of resource producers represented among the top corporate ranks over the last decade. Petroleum companies have become especially prominent, now providing 11 of the top 50.

I was surprised by the huge employment numbers racked up by the big financial firms: 370,000 workers employed by the dozen companies. (The RoB ranking reports worldwide employment of participating companies, but most of the banks’ employees are in Canada.) At the other extreme, the resource producers had very modest employment: just 82,000 in total. This means that the resource industry is the pinnacle of “exploitation” (measured loosely by after-tax profits generated per worker). On average, each worker at those 17 companies generated a stunning $325,000 in profit for their employers — compared to a comparatively stingy $75,000 per worker in the financial sector. Of course, it is not just workers that the oil companies and other resource firms are exploiting: it is the planet, too.

Our 50 big corporations reported year-end market capitalization of $1.15 trillion. Over 70 per cent of that total was claimed by the financial and resource companies. The big claim to fame of the proposed (and now rejected) merger of Canada’s TMX exchange with the London Stock Exchange was that it would reinforce Canada’s leading role as a place to trade resource stocks. I dare say that we are already a bit too heavily weighted on that score (and am glad the merger was rejected by TMX shareholders).

The rise of resources among Canada’s corporate titans is paralleled by the corresponding decline of manufacturers — mirroring the similar negative structural trend that has been so visible in Canada’s overall economy since the global commodities boom took off around 2003. A decade ago there were 9 manufacturing firms among the top 50; this year there are only 4 (RIM, Magna, Bombardier, and Agrium — the last included rather generously on my part as a processor as well as a distributor of fertilizers). Factory workers bust their butts on the shop floor for increasingly stingy real wages — yet they generate a mere $30,000 per head for their bosses. This relatively modest rate of exploitation reflects brutal price competition among firms in this globalized, over-capacitized sector.

The least profitable sector (per head) is the retail industry, whose 3 representatives within the top 50 sucked in less than $10,000 in profit per worker. Of course, the fact that most retail employees work short, irregular hours makes it hard to generate surplus value!

The transportation and utilities sector is another stalwart within Canada’s top corporate echelons. Nine companies are represented (including fantastically profitable telephone companies), claiming $12 billion in profit, over 175,000 employees, and $160 billion worth of market capitalization. Profits equalled $65,000 per worker, almost as high as the financial sector.

The finance, resource, and transport/utilities groupings are thus the major sectors of our economy where large, profitable Canadian-based corporations have developed. In the case of finance and transport/utilities, the fact that these industries are predominantly Canadian-owned (in large part because of strong regulatory restrictions on foreign ownership) is clearly a factor behind this corporate success. In manufacturing, on the other hand, where foreign-owned firms capture around half of all profits (according to Statistics Canada data), it has been much harder to build and sustain Canadian-based companies. The resource sector is a bit of an anomaly: foreign ownership in the sector is high (around 40 per cent of profits), yet a critical mass of Canadian-based companies has been sustained. It should be noted, however, that those Canadian-based companies have become more concentrated in the pure production end of the resource sector, as former value-added giants (like Alcan, Inco, and Falconbridge) fell under foreign control.

What would happen if the doors were thrown open to foreign investment in these once-protected sectors — as is now contemplated by the Harper government in telecommunications, among other industries? Most likely we would see a decline in the population of large, successful Canadian-based companies.

There is an increasing consensus among economists (not just lefties, either) that the absence of large Canadian-based corporations is a key structural factor behind the ongoing failure of corporate Canada to undertake innovation and successfully penetrate foreign markets (that is, with anything other than unprocessed resources). The analysis presented here is largely consistent with that storyline. Canadian corporations have been successful in largely non-tradeable infrastructure-type industries (finance, utilities, telecommunications, transportation), and also in resource extraction. Other than that, corporate Canada is underdeveloped and, if anything, atrophying further. RIM’s coming fall from grace, of course, will only makes matters worse on that score.

Despite this generally gloomy overview, one tidbit in the RoB ranking will bring a glow to any coffee-drinking Canadian’s heart. Company Number 46 on the RoB listing, reporting 2010 net income of $624 million, is none other than Tim Hortons — named after a Canadian hockey player, and having recently extricated itself from the arms of an American fast food giant. So while Canadian companies can’t seem to produce and sell high-tech products that the world wants (no wonder our current account deficit last year exceeded $50 billion, by far the biggest ever), they sure as hell know how to brew a good cup of coffee. Take that with your double-double!

Jim Stanford is an economist with CAW. This article was first posted on The Progressive Economics Forum.

Thank you for choosing rabble.ca as an independent media source. We’re a reader-supported site — visited by over 315,000 unique visitors during the election campaign! But we need money to grow. Support us as a paying member (click here) or in making a one-off donation (click here).