The violent Australian crime series with a wicked sense of fun, Mr Inbetween, ended this week after three seasons. Coincidentally this week, it got no Emmy nominations. It’s done pretty well for a show written by and starring an unknown, Scott Ryan, who’s been living with the character since 2005.

It’s been widely distributed without spawning the kind of frenzied online chatter common for (IMO) lesser shows. It’s modest in ways, including episode length (22-28 minutes each) and hasn’t been taken too seriously. The Globe‘s John Doyle, who liked the show, said of season one “there are no big ideas here.”

In fact I’d say it’s the most morally serious crime ‘n violence series I’ve ever watched. It’s been like a seminar based on the work of the greatest moral philosopher, Immanuel Kant. He coined “the categorical imperative” and the idea that people should — a very tricky “should” — be treated as ends, not means.

Take the severe violence in the show. (I’ll do my best to avoid spoilers.) Why is violence — as opposed to mere action — so mesmerizing in fiction? Other screen versions, like Sam Peckinpah’s westerns or Marlon Brando in The Chase, portrayed violence viscerally but rarely explored it. To be effectively violent, like Ryan’s character Ray, you need to treat the other as a thing, not a person; as meat, like a surgeon operating on someone they know (I’ve been told). If they suddenly morph back into a person, you’re befuddled, perplexed. You’re Mr. Inbetween.

When that happens, Ray sometimes backs off and goes away, leaving viewers and reviewers wondering why. He recognizes the seismic mental shift, though he might or mightn’t articulate it. Those are Kantian moments.

Outright murder is less fraught than sheer bodily harm, since it can be done at a distance through poison or guns. You don’t have to confront the “thingification” of a being like you. C’mon, how many TV shows make you think such thoughts?

For a great moral philosopher, Kant (1724-1804) was remarkably frank about how hard it is to decide in specific situations what’s right and wrong. He said the only unquestionably good thing is a “good will,” i.e., the desire to do the right thing. Beyond that vague guidance, you’re pretty much on your own.

He did offer rules of thumb (he called them maxims), such as: Always treat others as ends in themselves and not means. Ray has fine, complex, loving relationships with his daughter, brother, girlfriend and his “mates.” Yet he’s utterly means-end when on a job or (here it gets complicated) doing something he feels is morally required. It’s Kant’s alternatives, restructured for TV.

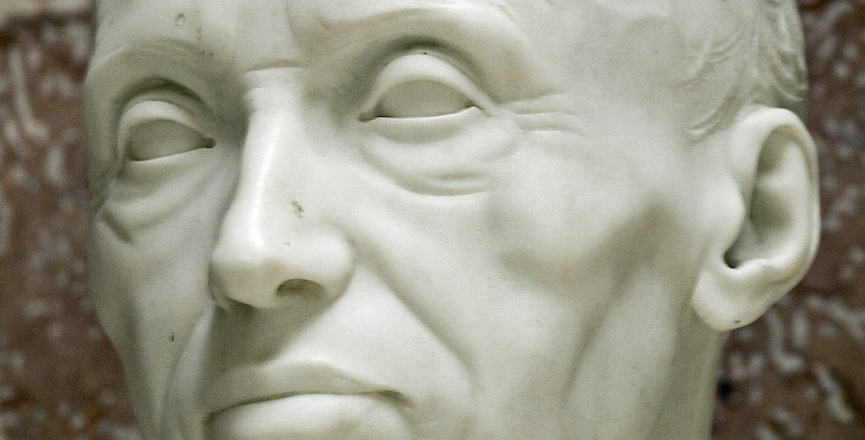

As for philosophy, he’s reticent but thoughtful. Socrates himself never wrote anything down and Ray looks a bit like Socrates in ancient sculptures: bald, self-contained and often preoccupied with knowing himself. This makes him way better than the titular character in Barry, I’d say, to whom he’s been compared. Barry gets to know himself, but doesn’t seem as naturally inclined to the pursuit.

You could call Ray a practical, as opposed to a theorizing, Kantian. He’s always situated between good and bad, right and wrong. Sometimes he’ll let one member of a crew off for a moral reason that occurs to him, even after doing in others. This almost embodies Kant’s other “maxim”: Act so that what you do could become a universal law for others to follow. With obvious qualifications.

I’d say he treats nearly everyone with at least a minimum of personal respect, and often more than that, including those whom he knocks (Aussie for “whack,” I gather). Respect isn’t an explicit Kantian ethical standard, but it is mine. The show is like a medieval morality play, which often had characters with names like Mr. Good and Mr. Bad, embodying those traits. This one adds Mr. Inbetween who, come to think of it, was called Everyman in those days.

The show kind of runs out of steam in its final season, so it’s probably good that they ended when they did. And if, for comparison, you want to go from the humbly sublime to the pompously ridiculous, I suggest you tune in, among other cases, to CNN’s smug, self-congratulatory History of the Sitcom on Sunday nights.

Rick Salutin writes about current affairs and politics. This column was first published in the Toronto Star.

Image: Ainunau/Flickr