The time is always ripe for a dirge led by the literati over the dire downfall of culture wrought by the Internet.

There’s one in last Sunday’s New York Times Book Review, conducted by Leon Wieseltier, former high priest for literature at The New Republic magazine. He sets a lofty, mournful tone: “Amid the bacchanal of disruption, let us pause to honor the disrupted. The streets of American cities are haunted by the ghosts of bookstores and record stores …”

There’s disdain for new technologies (“media, a second-order subject if ever there was one”) and for “the church of tech,” without acknowledging that there’s also a Church of Lit. Plus tributes to the previous technology, i.e. print, which happens to be the one he grew up with. Above all, he honours “the traditional Western curriculum of literary and philosophical classics,” a.k.a. the Great Books, that were once taught in HUM1 or Western Civ. courses. Teenagers I know would say: He sounds really old.

IMHO, Wieseltier’s piece is weaker than an earlier lament, Nicholas Carr’s 2008 Atlantic article, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” Carr too hyperventilated over the death of books (or “deep reading”) but at least also indicted people like himself, who say they can’t read long novels like Middlemarch anymore. Yet kids who gambol in cyberspace also gulp down Game of Thrones and other doorstoppers. Maybe the problem isn’t kids and books, it’s dads and the Internet. Carr was also gracious enough to say some critics of the written word (like Socrates) had a point, even if they missed the “myriad blessings that the printed word would deliver.”

An elegiac version of this theme airs on CBC Radio’s book shows, hosted by Shelagh Rogers or Eleanor Wachtel. There’s a hushed, reverential tone between hosts and authors, as if they’re broadcasting from the catacombs or confessional. Their shows could be called Bring Out Your Dead.

There’s often less than meets the eye in these testimonials. Take Wieseltier’s. He never mentions that his long whine follows a crisis at The New Republic last month when he and the mag’s other stars quit due to the new owner’s (a Facebook founder) plan to turn it into a “vertically integrated digital media company.” Or that TNR, once a liberal mainstay, had prostrated itself before Ronald Reagan and Reaganomics in the 1980s, then cheerled for George Bush’s war in Iraq. They’d become largely indistinguishable from the neo-cons except, in their case, you could prefix: Even The New Republic agrees — a tedious shtick found here among NDPers who say: You’ll find it amazing coming from me but I actually agreed with something Conrad Black wrote recently …

I mention this not out of bile alone but also because, if high bookishness like Wieseltier’s led to such scuzzy political results, you might wonder if a return to it is desirable in a time of political and moral crisis — marked by Charlie Hebdo attacks and an expanding military mire in the Mideast. Maybe it’s better not to urge a return to the literary wellsprings of western civ. if they helped take TNR down those paths but to ask instead: what in them encouraged those ugly outcomes? Does that sound bizarre? Who would even dare ask such questions?

Harold Innis, for one. He was Canada’s foremost scholar of the last century and creator, with Marshall McLuhan, of the “Toronto School” of media theory. He was the most renowned Canadian intellectual of the first half of the 20th century, an internationally hailed economist. He wrote many brilliant books himself. But he, like us, lived in times of economic gloom (the 1930s), political disease (the rise of fascism) and rampant violence (World War Two, Auschwitz, Hiroshima).

Instead of clinging defensively to the intellectual tradition he’d built his career on, he decided to question it radically, asking if the western cultural mainstream had somehow gone radically wrong. Where did all that deep reading get the human race anyway? He searched for alternatives in the moribund oral tradition. He knew nothing of the Internet, he barely knew of TV. (He died in 1952.) But he wasn’t afraid to question the cultural pillars of his and our existence. That’s my idea of an intellectual, not someone whose autonomic impulse is always to defend his familiar turf and his sinecure.

This column was first published in the Toronto Star.

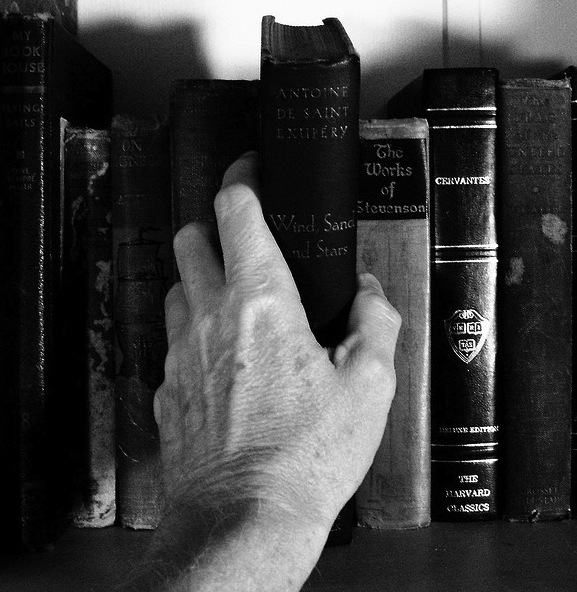

Photo: Patrick Feller/flickr