People of the Jewish faith around the world are observing Passover, the religious holiday that began at sunset Monday. It celebrates the liberation of the Jewish people from slavery, and their deliverance from the reign of the Egyptian Pharaohs. The Book of Exodus in the Old Testament describes Moses and his trials leading his people to the promised land of milk and honey.

Leadership is the first law of politics. The law says the exercise of responsibility and authority is going to take place. Leadership can be assigned by God — Moses serves as a heroic example — or by other means. In any event leaders emerge.

Western political societies have historically drawn on Greco-Roman civilization for inspiration about government and leaders. In Greek city-states it was understood decisions needed to be made, actions taken, direction be charted, and a vision of the future adopted. None of this could happen without leaders.

What held for the Greek polis also applies wherever politics is found: the law of leadership is universal. Whether it be the local government council or the world hegemonic power: politics requires, creates (and often suffers from) leaders.

People living in an electoral democracy make choices about leaders. Others may be governed by an absolute ruler, exercising authority like an Egyptian Pharaoh.

In various political settings a smallish group (an oligarchy) takes charge. The self-selecting loose organization finds the leader it needs, and provides support, resources, counsel and expects to be respected and compensated. Political parties have famously been depicted as oligarchies, even while masquerading as democratic.

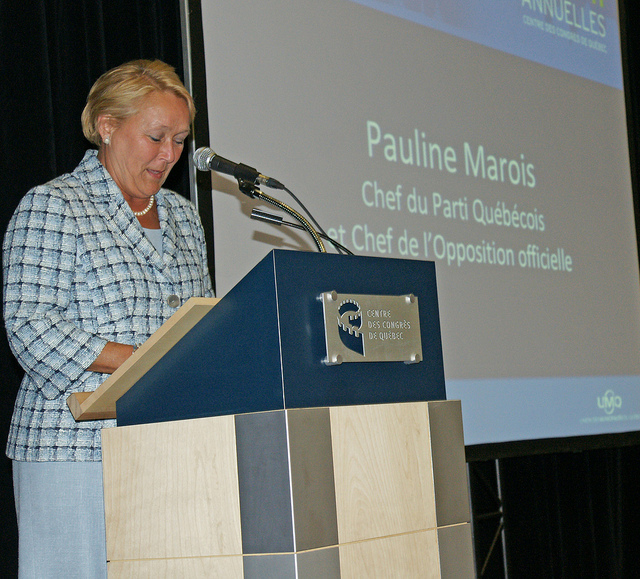

On the night she conceded electoral defeat, before Pauline Marois had announced she was stepping down as party leader, the PQ leadership race had begun on stage. Prior to her concession speech, three would-be successors took the spotlight and the microphone before she entered the room.

Just as the easiest way to report politics is to focus on leadership, the simplest way to explain a government election defeat is to blame the leader. It was a mistake for Marois to heed her advisers and focus on “identity” instead of building on her strength in economic and social policy. With another approach she could have added to her reputation as the creator of the widely admired Quebec child-care program.

Actually, as premier, Marois demonstrated important leadership traits recognized and admired by students of Moses: empathy and compassion. In the face of the tragedy of Lac-Mégantic, she avoided placing blame, even though an obvious villain was at hand in the Harper government. By her personal conduct and her manner of providing sympathy and support to a grieving community, Marios gained wide respect.

In 2012, about to address Quebec on the night of the election of her minority government, Marois was the target of a botched attempt on her life. During her acceptance speech, she was rushed off stage by security forces, who had somehow failed to guard a rear entrance where a would-be assassin claimed one life before being subdued.

After showing exceptional grace under extreme pressure, she refused to turn the attack by an anglophone vowing to kill the separatist into a political event, preferring to calm tensions rather than enflame prejudices.

The failure of the PQ election campaign revealed that it was correct in worrying about the appeal of the Coalition for the Future of Quebec (CAQ), but mistaken in thinking its proposed Quebec charter could destroy the appeal of the right-wing, small government, low taxes CAQ led by former PQ minister François Legault.

Running a campaign based solely on addressing social and economic issues, and providing needed public services and infrastructure was the alternative presumably rejected by Marois. Whatever the decision-making process, she and her party paid heavily for the strategy to focus on protecting Quebec identity.

From its inception the PQ has incarnated the idea of broad national coalition to achieve what was originally called sovereignty-association by party founder René Lévesque. Marois brought in Pierre Karl Péladeau (PKP) to demonstrate that PQ support included a business titan. Unhappy social democrats alienated by PKP and his anti-labour business practices either stayed home or migrated to Québec Solidaire.

After the first referendum loss in 1980, the party favoured its left wing, promoting itself as a good government, and had major electoral success in the subsequent election. The second referendum campaign in 1995 signalled a return to the PQ as a national coalition. Under Lucien Bouchard (who replaced Jacques Parizeau as party leader after the narrow loss) the PQ launched an anti-deficit campaign intending to rally all of Quebec behind a poorly disguised right-wing program designed by Bouchard, a former minister in the Mulroney government.

As PQ leader Bouchard misread the strength of the social democratic wing of the PQ; it resisted a move to the right. Within the party, influential hardliners wanted to push Quebec independence and a third referendum, and ignore right-left divisions.

With the defeat of the government led by Marois, leading the Quebec Exodus from Canada has just gotten harder. Building a progressive Quebec alternative that would contrast with the maniacs running the federal government is an approach with promise. Shelving the sovereignty option until such time as Quebec independence would seem the obvious way to escape an increasingly right-wing Canada has logical appeal.

Successively worse right-wing policies adopted at the federal level beginning in 1984 with Mulroney and culminating in the election of Harper in 2006 at the head of the most right-wing government in its history, make Canada less appealing and comfortable for not only Quebecers.

Duncan Cameron is the president of rabble.ca and writes a weekly column on politics and current affairs.

Photo: Parti Québécois/flickr